A discovery of hydrogen in Lorraine, France, made headlines in 2023. “Hydrogen deposit of staggering proportions” and “A gigantic hydrogen deposit in northeast France” were some of the quotes. With the appraisal drilling campaign by operator La Française de l’Energie (FDE) now on its way, it is time to take a closer look.

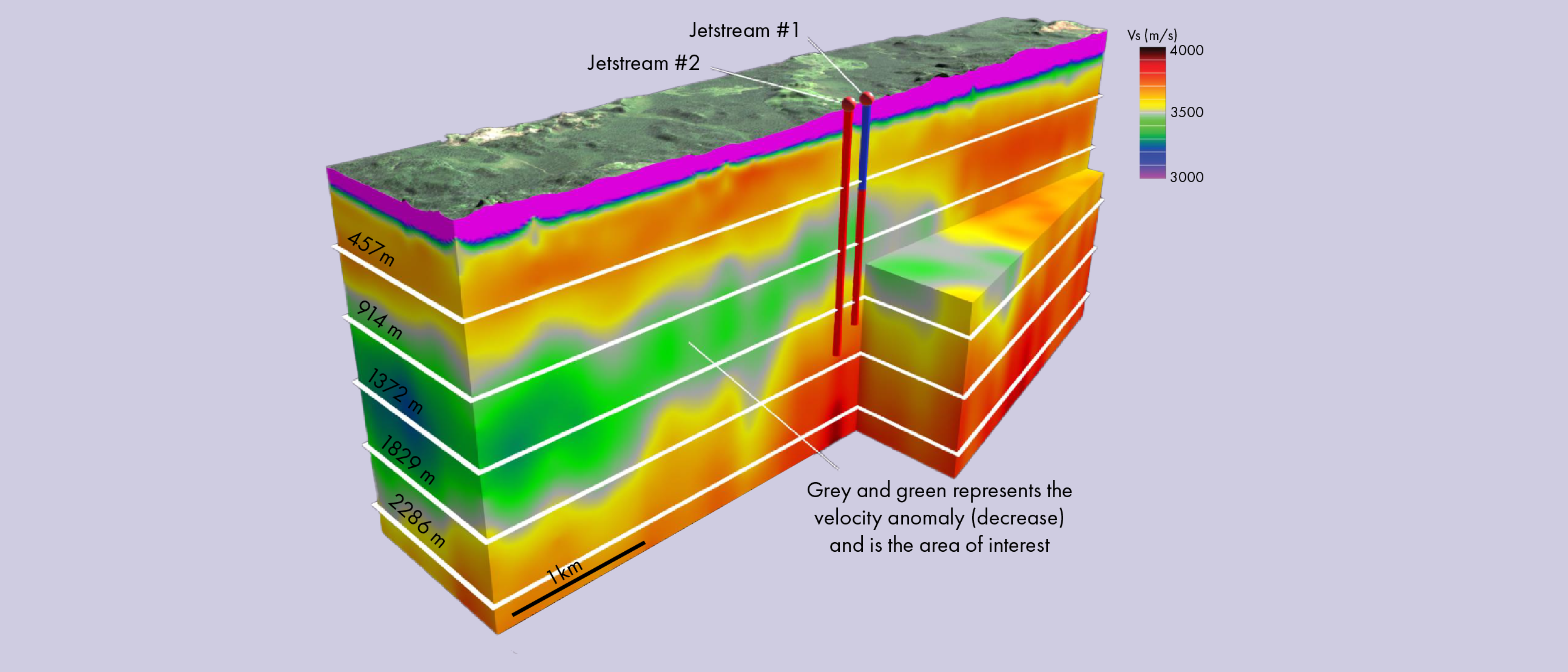

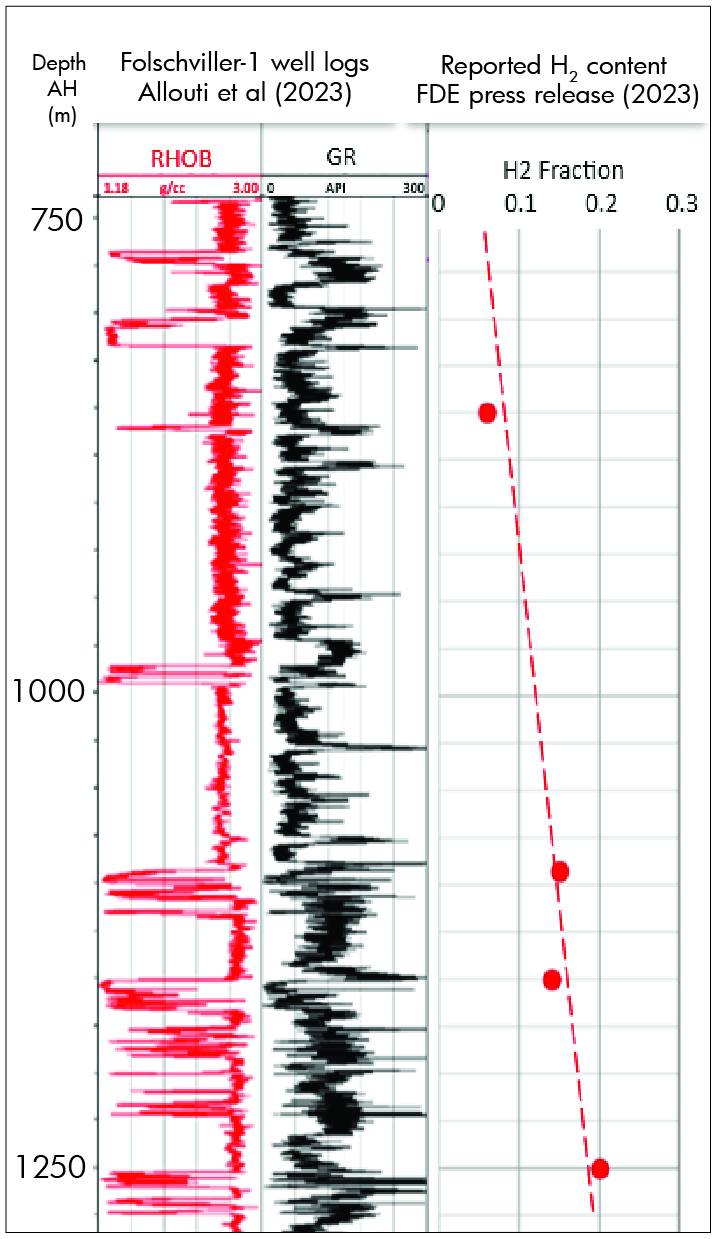

The Carboniferous Lorraine coal basin was mined for coal from the mid-19th century to 2004 and, from the 1990s, explored for coal-bed methane (CBM). The Folschviller-1ST/1A well, drilled in 2006 as a CBM test well, is where FDE reported a discovery of hydrogen. Investigations of this well are part of the EU-funded Regalor research program to study the viability of CBM exploitation of the basin. From Regalor study-results, we know that gas was detected in a succession of Westphalian coal seams varying from 4 to 13 m thickness, intercalated with sandstone and shale interbeds. Coal permeabilities from core are between 0.5 to 4 mD and declining with depth, as is usual in CBM assets. Gas content, also measured from core, varies between 7 to 10m3 per ton of coal. Presence of hydrogen in the gas was first noted by FDE when a gas chromatography probe-system was deployed in the well. Detected gas is predominantly methane but hydrogen content increases with depth from 6% hydrogen at 760m to 20% at 1250m; the average is around 13%.

Nature of hydrogen gas shows

FDE claims the detected hydrogen is dissolved gas and believe it may be derived from aquifer sands. However, Folschviller well data indicates the Carboniferous interbed sandstones are tight with a density porosity around 3-7p.u. and a permeability ranging from <0.0001 to 2.9mD. In fact, the Carboniferous interbeds must be tight for a CBM exploitation to be viable; if some were porous aquifers of significance, effective depressurization of the coals by pumping off water becomes near-impossible. Also, if porous aquifer-sands existed in the Carboniferous succession, these would have caused great difficulty in pumping dry and keeping dry the legacy coal mines.

A more plausible explanation is that the detected hydrogen-methane mixtures are derived from adsorbed gas in the coal seams. Assuming some coals are gas-saturated, gas may be desorbing locally around the wellbore and be picked up by the chromatography probe. Indeed, the depths of reported hydrogen occurrences coincide with the position of prominent coal seams. Coals have a documented capacity to adsorb large quantities of gas including hydrogen albeit they preferentially adsorb methane and CO2. Higher hydrogen content with depth may indicate a closer proximity to the hydrogen source but it could also be due to limited methane charge, leaving more space for other gases as adsorption capacity in the coals increases with depth. Isotope analysis of Folschviller gas-samples suggests methane may originate from coals buried to about 3km. Hydrogen may also have been generated from such deeper coals via pyrolysis.

Resource estimates

Media coverage of the Lorraine discovery speculated about a “monumental size deposit” of possibly 46Mt (million ton) hydrogen, quoting CRNS researchers. No basis for these estimates was given. A conference abstract estimated hydrogen resource of around 34 Mt for the entire Lorraine coal basin (16,000 km2), again without any details.

Publicly available gas-resource estimates for the permit and its surroundings allow a sense check of these numbers. In 2006, legacy operator EGL estimated about 28 MMm3 in-place gas resource in its Lorraine permit. With 13% hydrogen content in the gas and assuming an (optimistic) 50% recovery factor, this may amount to 170,000 ton recoverable H2 resource. In 2018, MHA conducted an independent resource assessment of FDE’s “Bleu Lorraine” permit and estimated around 2.1 MMm3 of recoverable gas (2P). With hydrogen content of 13%, H2 resource in the gas would be around 26,000 ton. Orders of magnitude below resource numbers suggested in the press.

Development outlook

Development of Lorraine gas resources would face the same hurdles that hamper CBM developments elsewhere in the world: low well productivity, high surface footprint and high co-production of water. Lorraine coals have not yet been flow-tested but considering their modest permeability, analogues suggest many hundreds or even thousands of wells may be needed to achieve full-scale industrial offtake. Such a full-scale development may then co-produce 10s of millions of barrels of water which would need treatment and disposal.

The deeper coals, with higher hydrogen content, would be tighter and more challenging to produce. Coals deeper than ca. 1,200m would be so tight that effective pressure depletion and drainage become near impossible. In fact, no analogue production of such deep coals exists. It is also noteworthy that hydraulic fracking is banned in France. FDE’s speculation of hydrogen content up to 90% at 3km is therefore merely academic: even if the coal succession extends to that depth, it would be too tight to produce from.

Another issue is the separation of hydrogen from methane. Effective separation, especially at low pressure and with modest hydrogen content, is technically challenging, energy intense and costly. However, separation is critical since industrial hydrogen-applications require purity of 98% or better, some require ultra-high purity (99.99%). If hydrogen cannot be separated and purified to industrial requirements, its presence in the gas mixture may not add value to a development since it actually lowers the gas heating value. Production pilots planned by operator FDE would unlikely be able to carry the cost of hydrogen separation and purification. If viable, a development of Lorraine gas at least initially, would be merely a coal-bed methane project.