Understanding sampling densities required to map the geology

Why high-trace-density seismic surveys will be required to accurately image reservoirs in the world’s major hydrocarbon-producing provinces. A case study

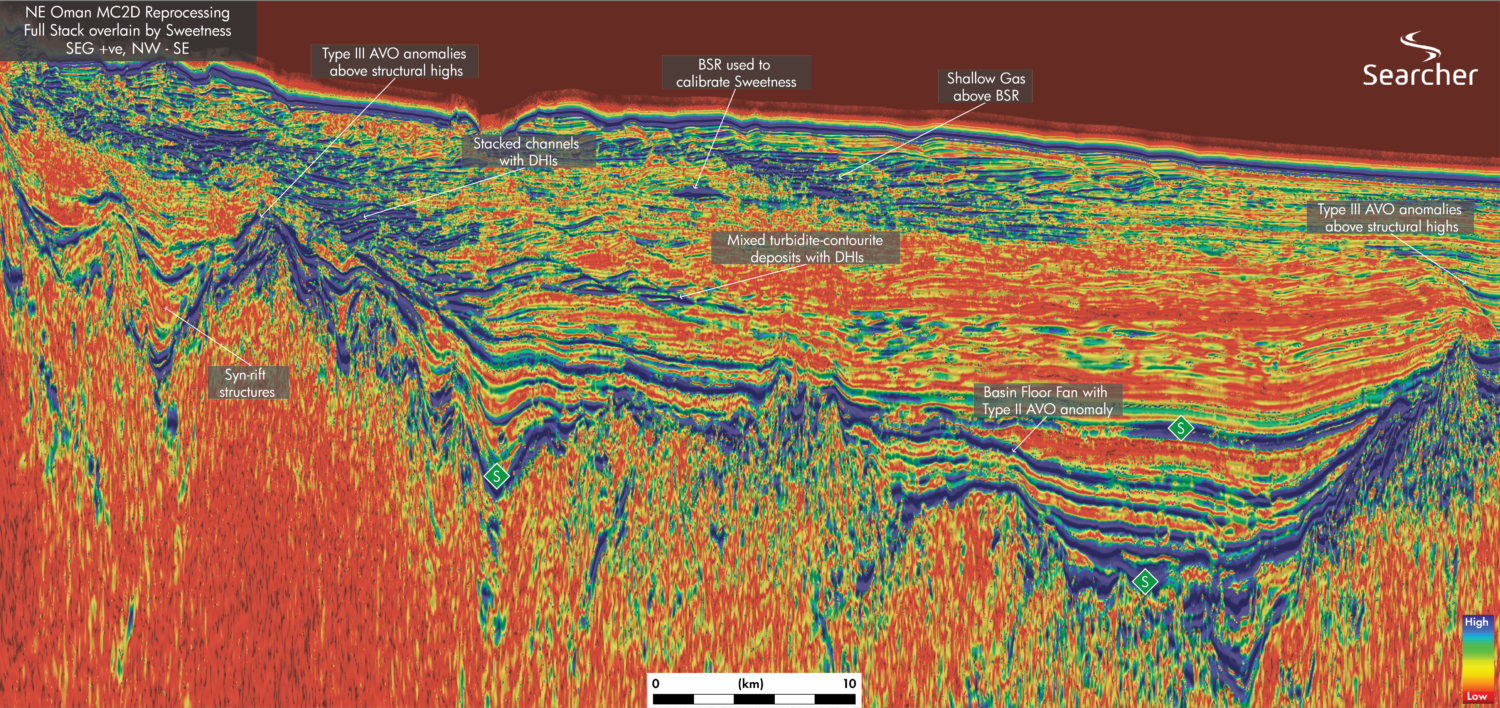

In some of the world’s most important hydrocarbon-producing basins, the shallow overburden is causing seismic data quality to rapidly deteriorate with depth. For example, in the Middle East, from Egypt to Saudi Arabia and Oman, shallow karst has historically caused the rapid deterioration of seismic signals. This is why the Middle East is being carpeted with high-trace-density seismic – both onshore and shallow offshore – to achieve this goal.

In some of the world’s most important hydrocarbon-producing basins, the shallow overburden is causing seismic data quality to rapidly deteriorate with depth. For example, in the Middle East, from Egypt to Saudi Arabia and Oman, shallow karst has historically caused the rapid deterioration of seismic signals. This is why the Middle East is being carpeted with high-trace-density seismic – both onshore and shallow offshore – to achieve this goal.

This trend has now also made its way to the USA, where similar challenges exist.

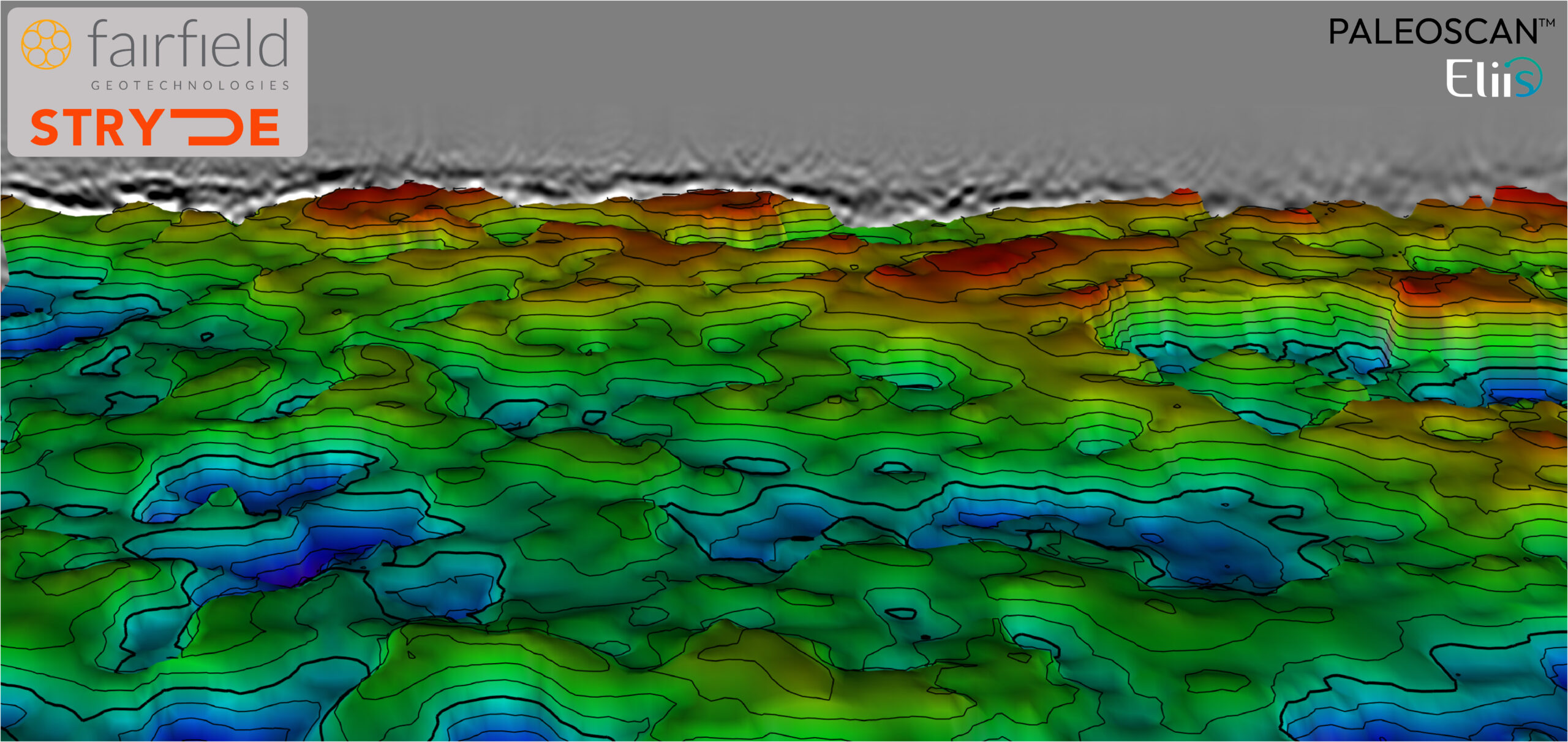

A consortium of companies operating in the Delaware Basin commissioned Fairfield Geotechnologies with the acquisition of an ultra-high-density survey in an area that has traditionally been challenging to image due to a complex overburden that includes salt dissolution features and associated collapse structures.

Here, Bruce Karr, Principal Technical Advisor and Andrew Lewis, VP of Geoscience, both from Fairfield, describe how the survey was optimised to overcome the shallow overburden challenges, how the project formed an opportunity to compare different nodes and how this concept may be required in other areas to tap into remaining resources effectively.

Salt dissolution

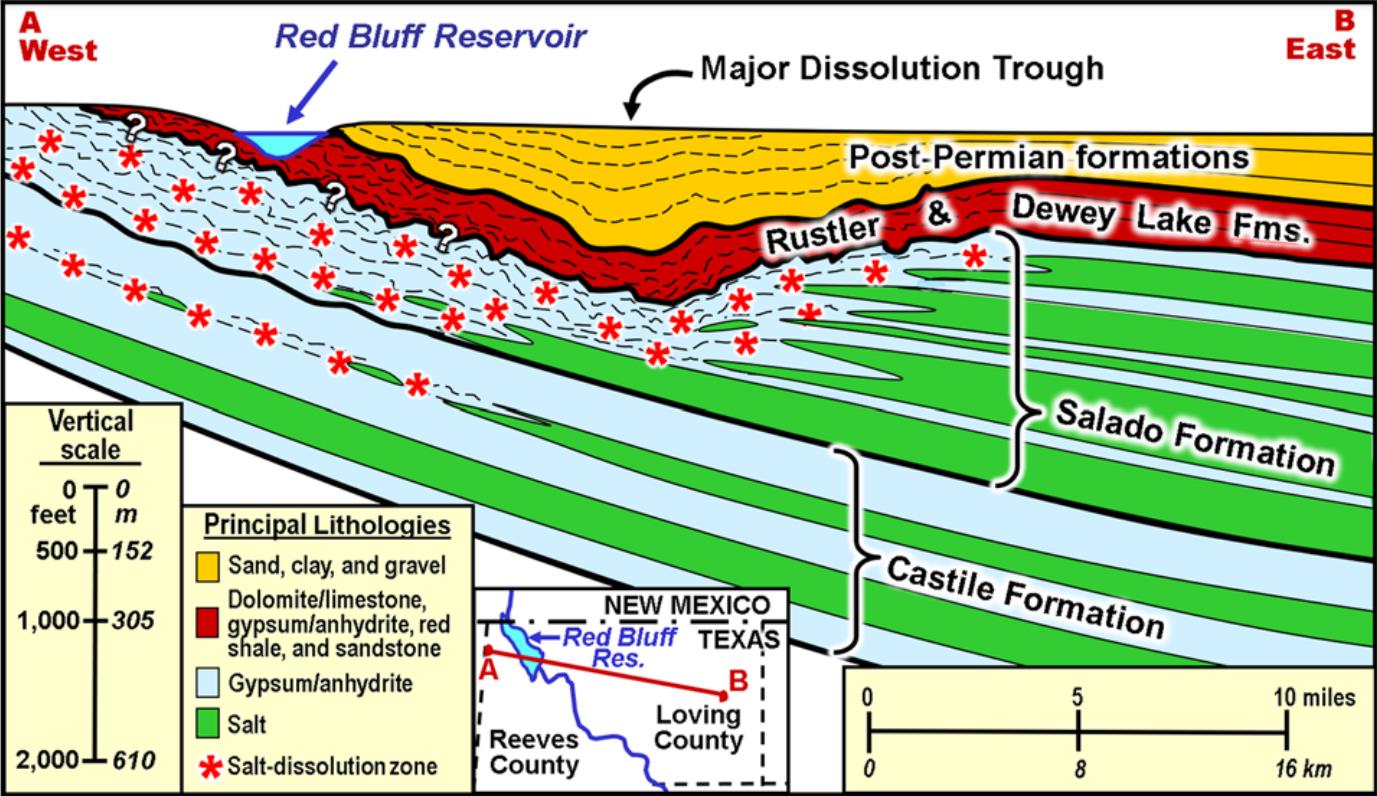

The Delaware Basin is located in West Texas and New Mexico. It is a basin with significant production of unconventional resources, which increasingly depends on more detailed seismic mapping; the Tier 1 acreage is increasingly being drilled out, and operators have to figure out how to economically produce Tier 2 and Tier 3 acreage that, while more marginal, still offers significant potential.

However, a challenge in the Delaware Basin has been over a regional area commonly referred to as “the Fill”, which varies in thickness, but can be over 1,000 ft thick in the shallow subsurface. This succession, which is a combination of Permian, Triassic, Tertiary and Quaternary strata, has experienced collapse due to salt dissolution in the Permian Salado Formation, which consists of intermixed halite and anhydrite layers in this area.

Especially the Permian-aged Rustler Formation, which directly overlies the Salado, experienced collapse into the Salado, resulting in a heavily fragmented overburden stratigraphy and strong lateral structural changes and associated lateral velocity variation.

“Every geophysicist has their own explanation as to why they couldn’t see the deeper reservoirs, but a combination of scattering, dispersion, absorption and insufficient source energy is probably a good summary,” says Bruce. “That’s why,” adds Andrew, “when developing the unconventional resources beneath the Fill, seismic data has so far not played a major role simply because the resolution was not there.” Until recently.

Limited by equipment

“We had already done some projects using high-trace density surveys in the Midland Basin,” says Bruce, “and the results were promising. That led our partners / Permian Basin operators to also think about similar applications in the neighbouring Delaware Basin. So, it was great to find a consortium of four operators willing to test this with us last year.”

But finding the desired sampling density required some conversations. “What if it is not even dense enough for what you are trying to achieve?” was a question Bruce had to reply to on multiple occasions.

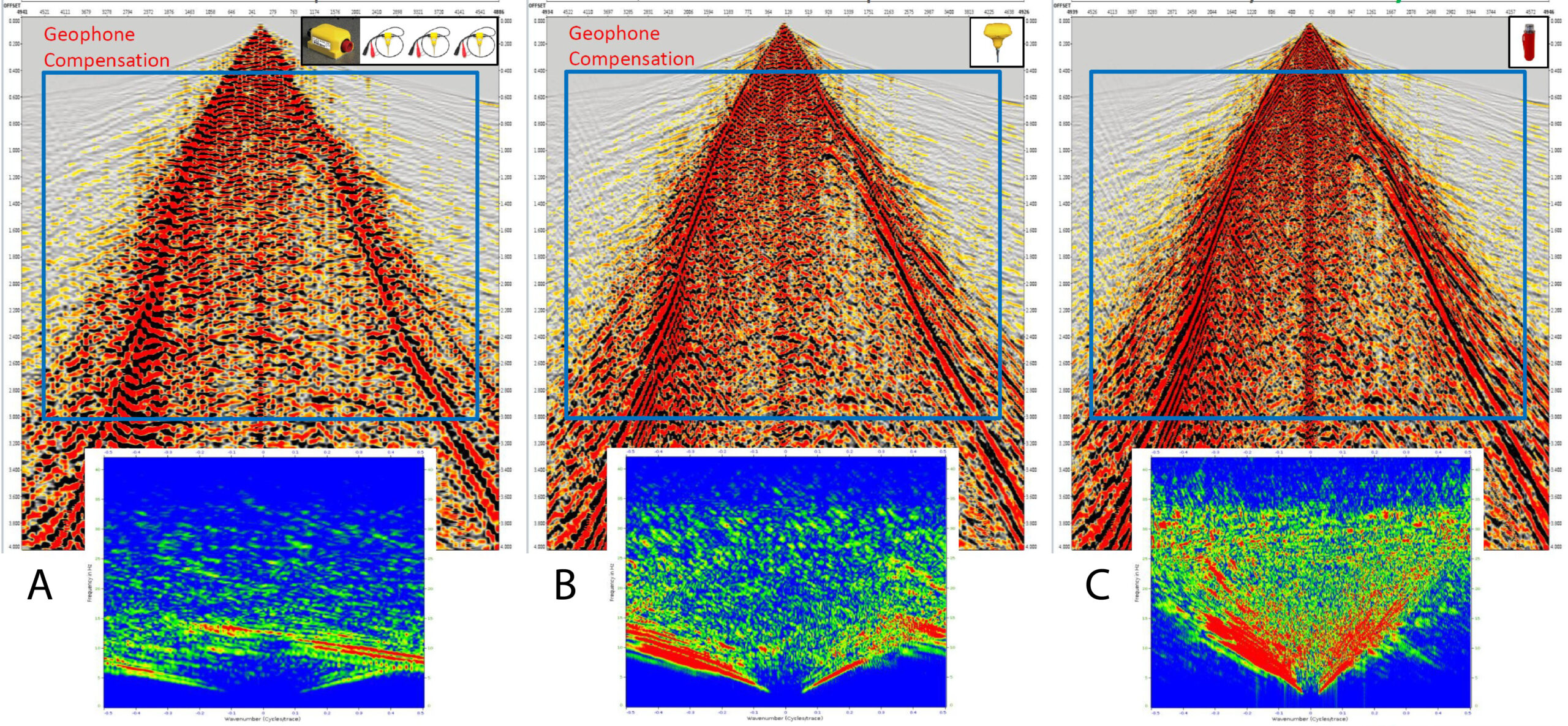

Initially, the number of receiver lines and stations, laid out with 2,816 Geospace 10 Hz cabled geophones, was doubled from a 495 ft x 82.5 ft spacing to a 247 ft x 41.25 ft spacing using 11,008 INOVA Quantum 5 Hz nodal receivers. But, to convince the fourth operator to participate, Bruce was asked to reduce the station spacing even more, to a value below 30 ft. “This is where the STRYDE nodes came in,” he explains. This configuration added another 22,016 autonomous nodal receivers at a 247 ft line spacing with 20.625 ft station spacing, at the same cost as the other 13,824 nodes deployed.

Tool comparison

“We did not plan to use nodes from multiple vendors, and it was not a request from the operators at all, but the number of receivers we required was so large, we had to source material from all corners of the area,” says Bruce. “The benefit was that we could also compare the nodes with each other, which was a nice spin-off from the project. Andrew presented this work at the EAGE Land Seismic conference in Calgary earlier this year.

“The conclusion was,” says Bruce, “that all three nodes were capable of capturing the low-frequency domain (4-5 Hz) equally well. Some people in the industry claim that the STRYDE nodes, which register acceleration rather than velocity, are less well-suited for lower frequency domains, but following integration of the STRYDE node data into the velocity domain, we saw that all three performed well.” The signal-to-noise ratio was also similar between the sensors, with the Quantum and STRYDE ones appearing slightly superior to the GSR ones.

Scaling up

“The operators who supported the seismic acquisition project have seen enough to be confident about the added value of what we are doing,” says Bruce, when we continue about how to scale up this survey design.

However, repeating the exact same survey density is not without its challenges. Let’s look at some numbers. “The Delaware Basin has got about 2,000 mi2 of “Fill zone” to shoot,” Bruce explains, “where this survey only measured 4 mi2.”

“That’s why we are currently at the intersection of what is economically possible and still technically sound,” adds Andrew.

“We are currently acquiring our third high-trace-density production survey in the Delaware Basin that doesn’t have the same level of density as we used in the “Fill” project, but still changes the game when it comes to how seismic can now be used in this basin,” he adds. “We have to be creative and match the problem to the available equipment and budget.”

Ultimately, it boils down to feasibility and ROI. “We need to be thinking critically about where to go for higher trace density and where we won’t,” concludes Bruce. “But the fact remains, high-trace density acquisition will become a more and more important aspect of our continued search for remaining oil and gas resources – and it’s the receiver technology that will ultimately determine how achievable this is.”

This is where innovation in receiver system design becomes a game-changer. The choice of receiver technology fundamentally shapes crew composition and overall seismic camp costs. By utilising miniature, ultra-lightweight receivers and high-capacity node handling infrastructure like STRYDE’s, operations can be leaner, faster, and more cost-effective, including in traditionally high-cost environments like the USA.