“We are changing the world of exploration,” says Denis Krysanov from Heologic, when we meet on Teams. “I’m now planning on expanding Heologic’s operations in the United States,” he says. He currently lives in Argentina, but he’s been in the Middle East and Asia for work before.

Helium anomalies in the subsurface are first and foremost an indicator of the presence of hydrocarbons. “And the good thing about helium is that it moves through the subsurface vertically – it is so small that it is not deviated by subsurface irregularities. So, when we see a helium anomaly, we can be sure that the hydrocarbon reservoir is straight down there,” Denis explains.

However, until recently, the technology used to measure helium anomalies was not really able to “map” subsurface helium anomalies properly. “You can’t go into the field, take samples, and analyse them in the lab for helium. It is simply too light; as soon as you sample it, it will mix with ambient air, and you will not measure the real concentrations,” says Denis. “On top of that, helium fluxes change during the day, as well as with the lunar cycle. For all those reasons, helium surveys were, until a few years ago, only capable of detecting major fault zones, as it is in those places where helium concentrations are big enough for these systems to detect an anomaly.”

“Based on these limitations of the “old” technology, we decided to take the lab into the field and take the measurements in situ. The devices we use are ultra-sensitive and collect data for about 15 minutes at each sample location, before the system allows the crew to move on; in other words, the software comes with a built-in quality control system that checks the validity of the acquired data on the spot.”

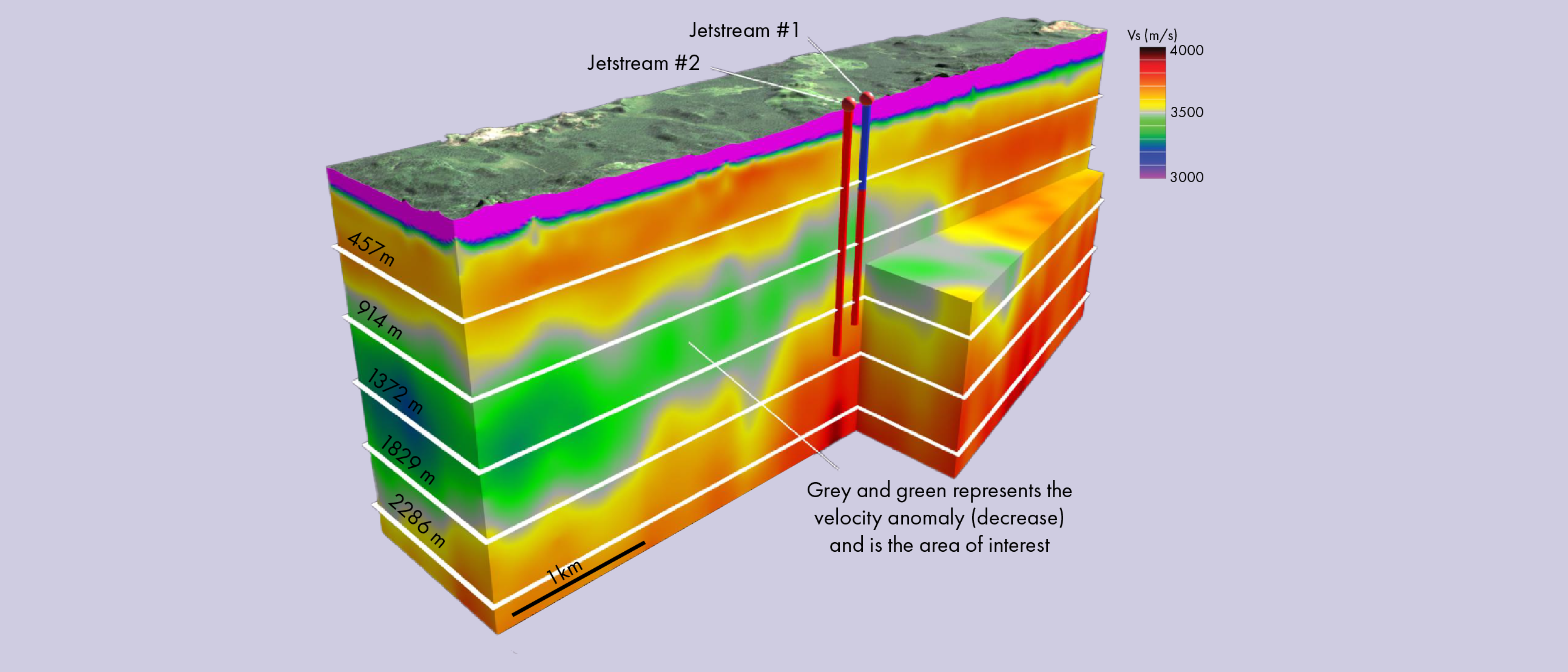

The level of accuracy of these systems is far better than previous generations, to the point where Denis and his team can even detect channel systems in the subsurface, once they start integrating their data with subsurface information. “In addition, the magnitude of the helium anomaly allows us to distinguish between different fluid types, and even the depth of burial of the hydrocarbon reservoir. We are now even working on projects whereby we aim to disentangle an oil versus gas signal in the same place.”

And mapping helium anomalies can not only be used for highlighting new drilling targets, it can also be used for identifying opportunities in mature fields, says Denis. We carried out a project in Southeast Asia, where we surveyed a field with 30 wells already drilled on it, which had ceased production. However, our data suggested that a large anomaly still existed in one corner of the accumulation, lending support to an infill opportunity.

The next frontier for Denis is going offshore, which also explains his move to Houston. “We have already done campaigns in shallow waters, ranging from a few meters to about 300 m, and also in these circumstances, the signals we acquire are reliable,” he says. “That’s why we are now looking for investors, to help grow the company to such an extent that deep water surveying becomes a possibility as well.”