As competition for upstream investment intensifies, countries across the globe have responded with a wave of fiscal and regulatory reforms aimed at attracting limited capital. Since the 2014 oil price crash, upstream capital availability has declined dramatically – from a $779 billion peak to around $550 billion annually – forcing governments to rethink their hydrocarbon strategies. Between 2019 and 2025, at least 72 countries introduced major changes to their petroleum fiscal frameworks. Most of these reforms have been investor-friendly, though a minority of jurisdictions have pursued more adversarial paths.

Investor-friendly reforms dominate

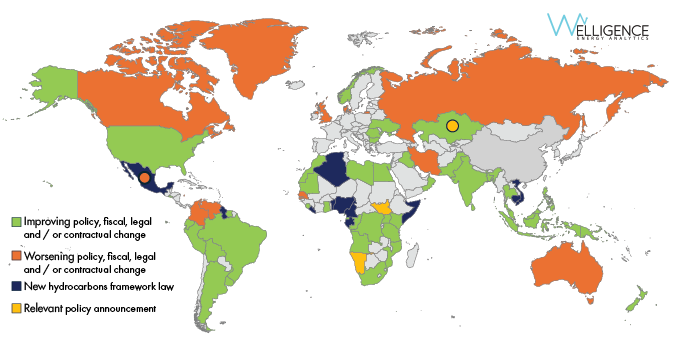

Out of the 72 countries that enacted reforms, 62 made positive changes, including targeted incentives for mature or undeveloped assets, adjustments to model contracts, or complete fiscal framework overhauls. Some countries, such as Angola, Nigeria, and Brazil, focused on enhancing their existing fiscal regimes. Others, such as Libya and Indonesia, introduced new model contracts designed to improve operational flexibility and bankability. Meanwhile, jurisdictions like Guyana, Vietnam, and Gabon opted for full-scale legal and regulatory overhauls, aiming to modernize outdated petroleum laws and respond to changing investor expectations.

Key motivations behind these reforms include declining domestic production, a reduced pool of E&P capital, and growing urgency to monetize stranded or underexplored assets that may lose relevance amid the energy transition. Governments also increasingly recognize, that without robust fiscal incentives – especially for small and mid-sized operators – access to financing will remain constrained.

Regional reform leaders

Africa has emerged as a leader in investor-friendly changes, with 25 countries reforming their fiscal or legal frameworks. Southeast Asia also stands out, with every hydrocarbon-producing country implementing changes. In the Middle East, Oman and Iraq have introduced new contractual models aimed at providing more flexibility and improved upside potential. Latin America, however, presents a mixed picture: While Brazil, Trinidad & Tobago, and Uruguay moved toward greater competitiveness, Mexico and Colombia introduced investor-adverse policies.

A small group moves against the tide

Ten countries took countercyclical actions that may deter investment. These include windfall taxes in the UK, exploration contract halt in Colombia, and the partial reversal of the 2014 energy reforms in Mexico for a more state-centric approach. Such measures, often driven by political or ideological motives, can damage investor confidence and may be difficult to reverse, even under new leadership.

What comes next?

While fiscal terms are a critical component of investment decisions, they are only part of the story. Other factors include the cost of entry, regulatory efficiency, and implementation capacity. In today’s capital-constrained environment, governments not only need to offer competitive terms – they must also execute efficiently to convert interest into investment.