“I do obviously worry about the ecosystems down at the seafloor,” says biologist Annemiek Vink from the Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe (BGR) in Hannover when we meet on Teams. “On the other hand, I also appreciate the impressive size of the resource.”

“There are environmentalists who claim that if you remove all the nodules, an entire ecosystem will be lost. But that is impossible,” Annemiek says, “because the areal extent of these nodule fields is so huge that it will never be possible to mine it all. In fact, even if we were to aim to mine 20 % of it, it would still take us hundreds and hundreds of years to do it.”

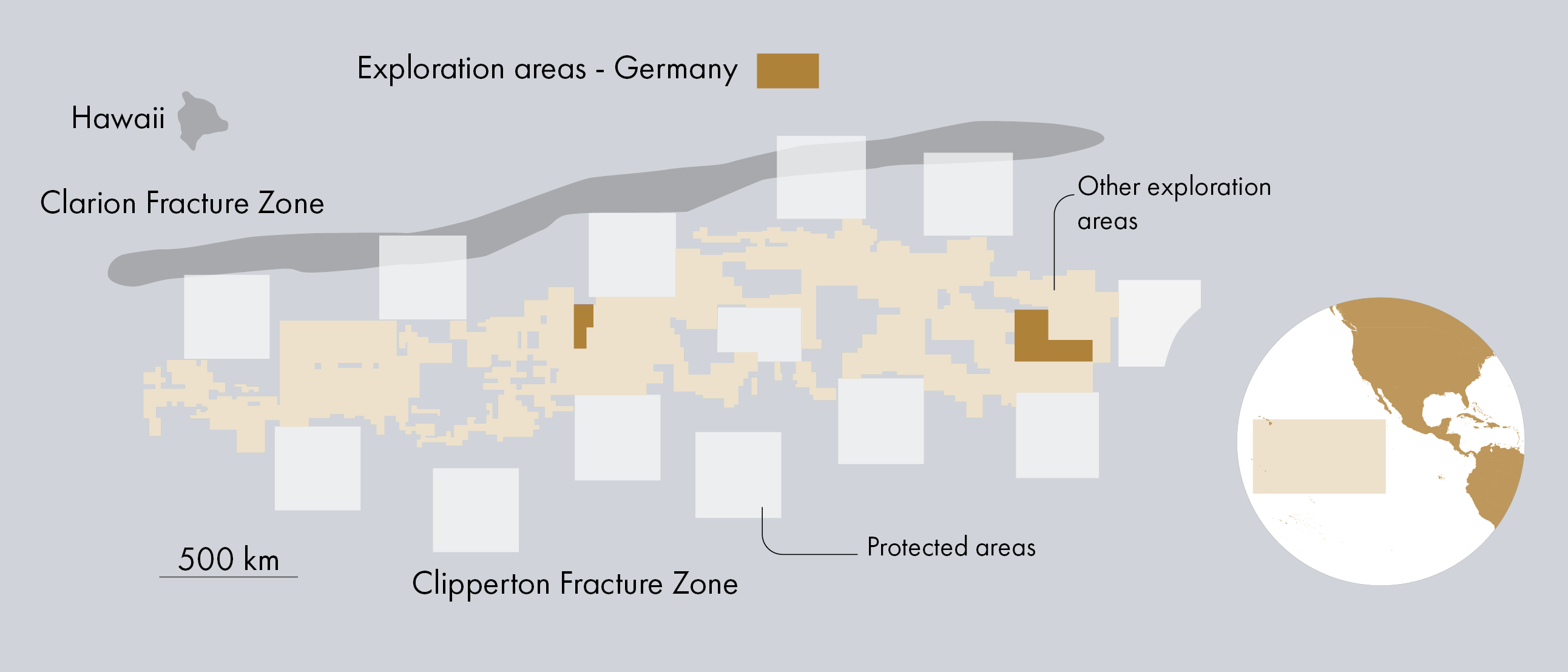

“If you see these nodules lying on the seafloor through the camera of an ROV, and you know that that seascape continues on for hundreds of kilometers, it makes you more aware of the sheer scale of the area these nodules are covering,” adds Annemiek. The Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) alone is equal to the size of Europe.

However, it is only a smaller part of that total area that lends itself for seabed mining. There are mountainous areas where mining would be much more complicated, in addition to areas where the density of nodules does not make a mining exercise an economic exercise in the first place. “Taking these things into consideration, it is 20 % of the CCZ that is mineable at most,” explains Annemiek.

Unique ecosystems

“Most of the species we find in this environment are rare; it’s not like in forests where you see many common types of trees or birds across large regions with some rarer species alongside,” says Annemiek. “That means diversity is high and difficult to quantify, with the implication that we will never be 100 % sure what species reside at every location. However, I feel that we should not even try to attempt to do that, simply because that would be an overly complicated and impossible task, also because we are not nearly close to having this information on land either.”

“Instead, what we need is a pragmatic approach and a process that allows us to protect important parts of this ecosystem without the need to completely avoid other activities. In my view, that is possible. If we can have large and ecologically robust protected areas that are 80 % similar to the areas that will be mined, we are already in a good position. This will also help re-colonize mined areas.”

TWO EXPLORATION CONTRACTS

Germany has two contracts for the exploration of seabed minerals in international waters; one in the Indian Ocean for polymetallic massive sulphides and the other in the CCZ for polymetallic nodules. Annemiek coordinates the polymetallic nodules project in the CCZ, which started as far back as 2006. Meanwhile, about 80% of the work in the area relates to environmental baseline and impact studies.