“Why would we still explore for oil and gas?” asked René Jonk from ACT GEO at the end of his talk for the Geoscience Energy Society of Great Britain this week. René, a seasoned explorer and geologist, put this question to the audience after giving an overview of how exploration over the past decades has also depended on good fortune in the face of uncertainty and risk.

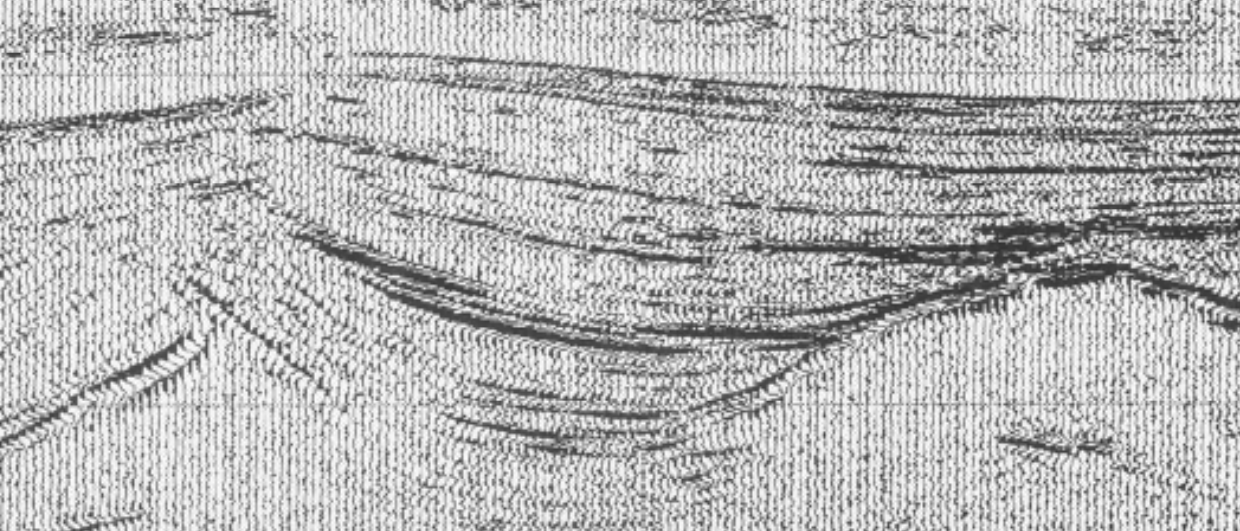

The discovery of the Golden Lane in the Suriname-Guyana Basin is an example of such good fortune. Around the time of the Liza discovery in 2015, Apache was drilling a couple of unsuccessful wells in Suriname. Even though ExxonMobil had held the Stabroek licence in Guyana for a long time, it had been on the fence about drilling for years, and certainly did not aspire to be 100% in it at all, given the farm-out after partner Shell walked away in 2014.

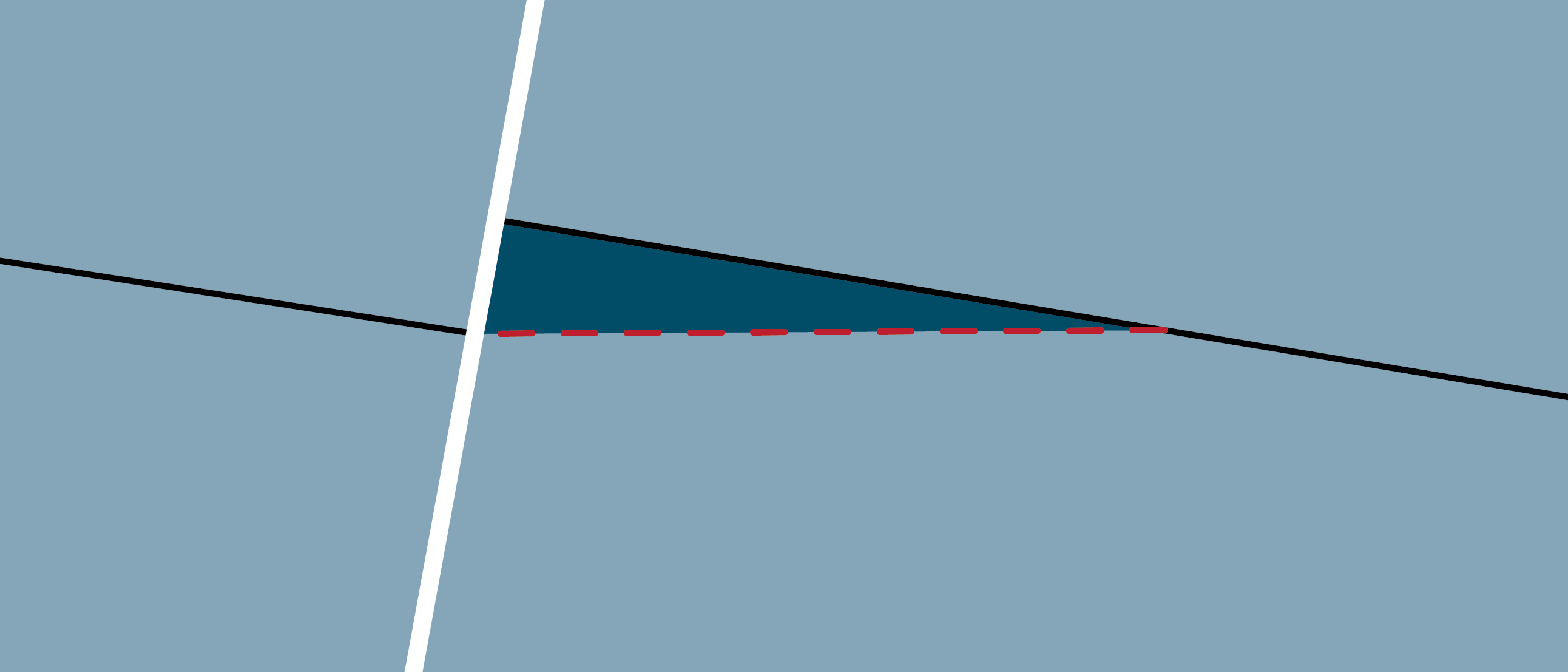

“There were two prospects shortlisted for drilling in Guyana,” said René, “Skipjack and Liza. If Skipjack would have been drilled first, which did not happen at the end, the Golden Lane might just as well still be undiscovered at the present day.” The second well Skipjack was dry. But fortunately, Liza was drilled first, and the rest is history. It is hard to see that there is not some element of luck in ultimately finding a new Golden Lane. However, it is important to keep in mind that you will not generate your own luck if you do not explore, something René elaborates more on in this recent video.

Read more about the Suriname-Guyana Basin here

Back to the question asked at the start. Why don’t we stop exploring?

“Well”, said René, “the mantra is that if your portfolio is static, you’ll ultimately lose market share. It is one of the pillars of many companies operating in this area – there is the ultimate goal to reach above the competitor.”

Then, as a second argument, there is the observation that a lot of the world’s reserves are locked in as heavy oil. With the carbon footprint of heavy oil production being so much higher than for more conventional oil production, there is a strong incentive to look for these conventional reserves. Also, the lifting costs of conventional oil may be lower as well, if you don’t need to rely on steam injection etc. At the same time, the costs of ultra deep-water developments like Venus in Namibia should also not be sniffed at either.

The third reason to keep on exploring, and that is a factor that has come to the fore a lot in recent years, is security of supply. It is one of the reasons, if not the most important one, for New Zealand to start discussing opening up for exploration again last year. No doubt security of supply is also a big drive in KNOC’s efforts to firm up domestic reserves, even though that has apparently not been very successful yet given the dry well that was recently reported.

A fourth factor that I could add to this is that some countries will simply want a share in the wealth oil and gas can generate. Guyana, Suriname and Namibia are prime examples. And the opportunities are real; a news item in the Netherlands recently highlighted the opportunities that currently exist in Suriname. A sparsely populated country today, there is a big recruitment drive going on to find skilled people to build up the infrastructure to support imminent oil production from the recently made discoveries.

So yes, despite the seemingly obvious answer to the question posed above, the answer is more complicated and is reflected in what still happens today; continued oil and gas exploration.