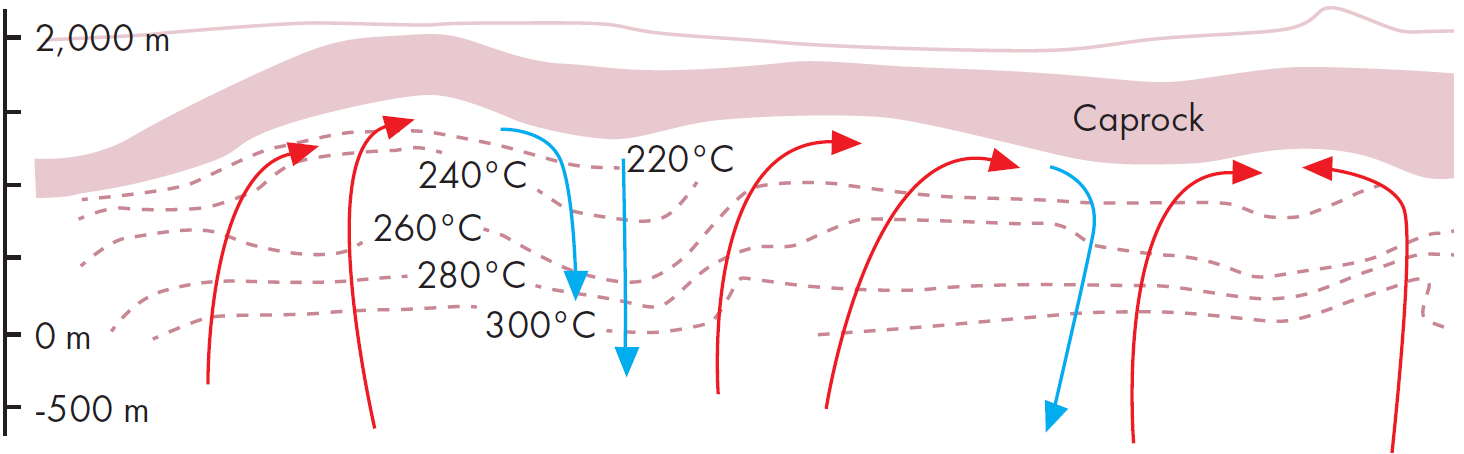

In Geothermal energy production, it is all about the temperature of the produced water, brine or steam. A drop in temperature has a direct effect on the amount of energy that can be extracted.

The timing of thermal breakthrough in a geothermal project depends on a few factors. The proximity of the injector well to the producer well plays an important role, as well as the properties of the rocks – are there any high-permeability zones – and / or the presence of natural recharge through which cooler waters can arrive at the production well? And last but not least, the rate at which geothermal fluids are produced also determines the timing of thermal breakthrough to a significant extent.

It is the latter that seems to have been an issue in Kenya at a couple of the countries’ high-profile geothermal power projects.

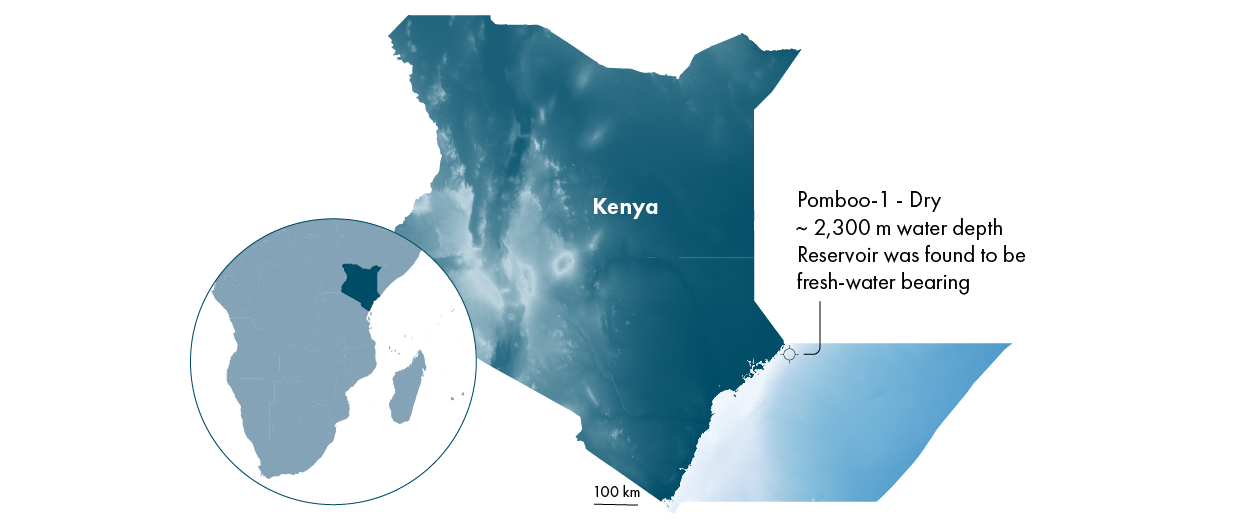

Kenya is home to a well-established geothermal production province in the African Rift, where steam is being produced from moderate depths of around 2,000 m for electricity production. As such, Kenya occupies the eighth place in the world when it comes to geothermal energy production, with an estimated capacity near 900 MW.

The question now is whether the 900 MW capacity can be maintained through the existing projects alone. There are signs it will be a challenge. As we reported earlier, the development of the Olkaria geothermal field has now reached a mature stage, and there is an increasing risk of well interference and drilling of unproductive wells.

And this may have already happened, with early thermal breakthroughs taking place at some key wells across various projects in Kenya.

Reservoir complexities may be one of the reasons why this has happened. At Olkaria, the main reservoir consists of porous and permeable volcanic rocks such as rhyolites, trachytes and basalts. It can be easily envisaged that without mapping of individual flow units, it is hard to predict where “thief zones” are.

It is possible to suspend production from that well and give it time to recover, but without understanding why the breakthrough happened in the first place, it probably will keep occurring.

All of this illustrates that geothermal energy production is not a simple exercise that entails drilling a production and injection well. It needs both geoscience to map out reservoir heterogeneities as well as a reservoir engineering approach to keep tabs on what is happening. This is not to say that these things were ignored in Kenya, but it rather reinforces continued vigilance and also illustrates the need to keep thinking about “replace reserves”.