As we enter a new year it’s always important to ponder what we have learned from the previous year. I discovered that most people think that energy is simple and that their own preferred solutions are all we need; we’re all victims of our own confirmation biases after all. But as a community, we should be leading a more robust discussion.

Supplying 8+ billion people with energy security while minimizing harm to the environment is a big and complex problem and that is why energy density matters. Ultimately, the best solutions depend on your geography – your ‘geological endowment’. Folks in Iceland can rely on geothermal, Norwegians rely on hydro for their electricity, but most people around the globe burn coal and natural gas for their energy needs. And of course, industrial processes, transportation, and home heating – those are largely oil and gas almost everywhere.

It’s very convenient to be a reductionist when living in the wealthiest European countries because the reductionist position is the only one compatible with fewer hydrocarbons and nuclear energy. But here’s the kicker: What about the couple of billion people on this planet stranded without access to energy, or the billions of people that are just a recession away from energy poverty? I believe 2025 is a year in which we need to get back to the fundamentals of consuming more high net energy, as that equates to human prosperity.

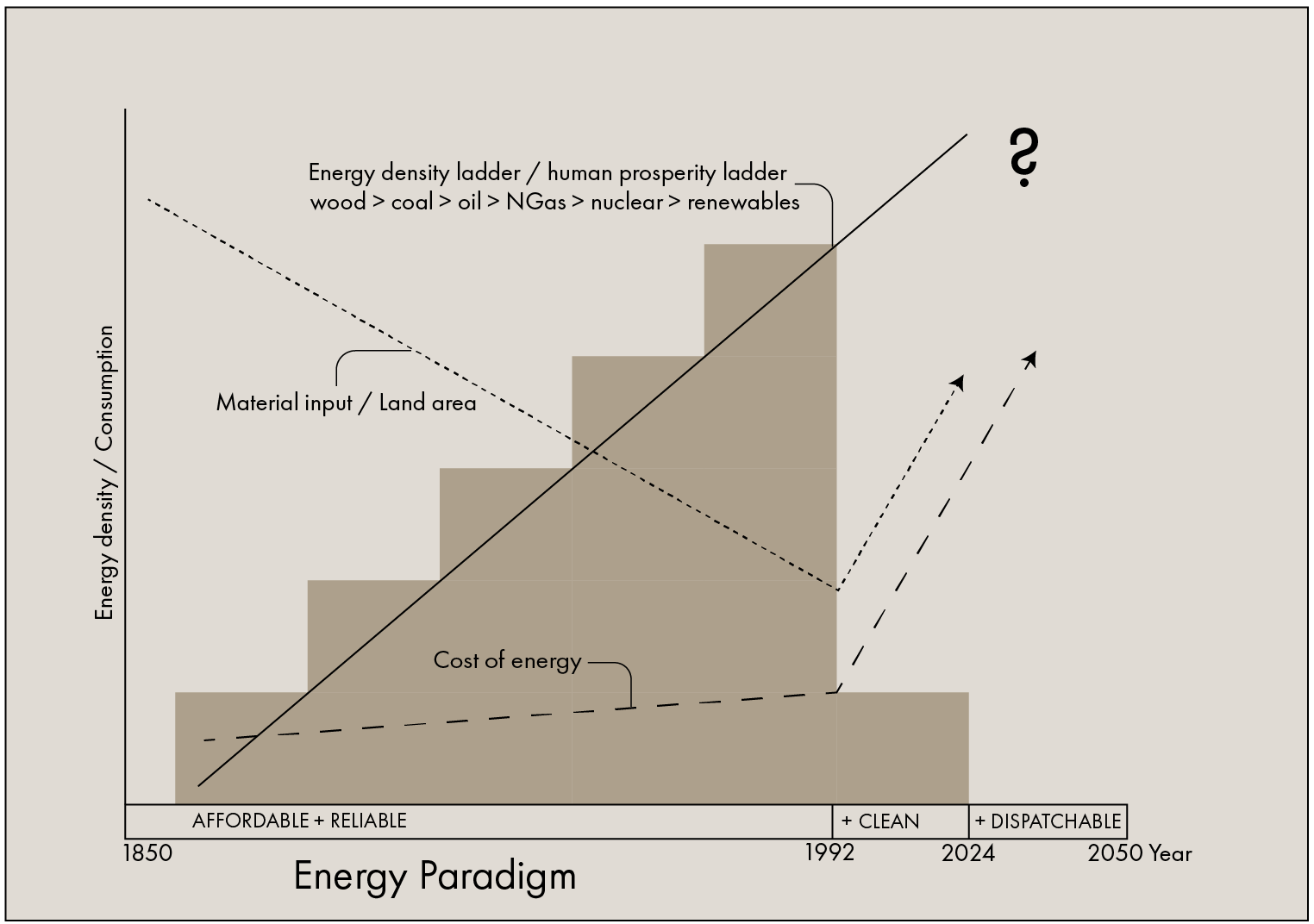

Governments around the world prioritize energy security – up until very recently it had to be affordable and reliable. Then ushered in the Kyoto Protocol in 1992 and energy had to be ‘clean’ too. We are now entering a 4th energy paradigm, whereby energy must also be dispatchable. The type of transition ongoing now is a huge experiment with no data from similar trends in earlier historical transitions with increasing energy density over time. What it also shows is that global demand for energy will continue. Load growth is conveniently downplayed.

2025 marks not only the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, but is also the end of the era that began with the fall of the Berlin wall, Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history” and the Kyoto Protocol. Hydrocarbons are transitioning away from us now, and it is partly because of this that the future looks a lot more serious than the past we leave behind. We find ourselves in the middle of this turmoil, and we will probably have to take more pragmatic and realistic decisions than what our parents did. In the long run, maybe that will be for the better though.