During an evening lecture organized by the Geoscience Energy Society of Great Britain (GESGB) in Aberdeen the other day, a discussion unfolded about how to risk play elements in a mature and heavily-explored basin such as the North Sea. It followed on from a talk delivered by John Seedhouse from the North Sea Transition Authority, during which he presented an overview of exploration results over the course of the past few years.

Risk allocation concerns

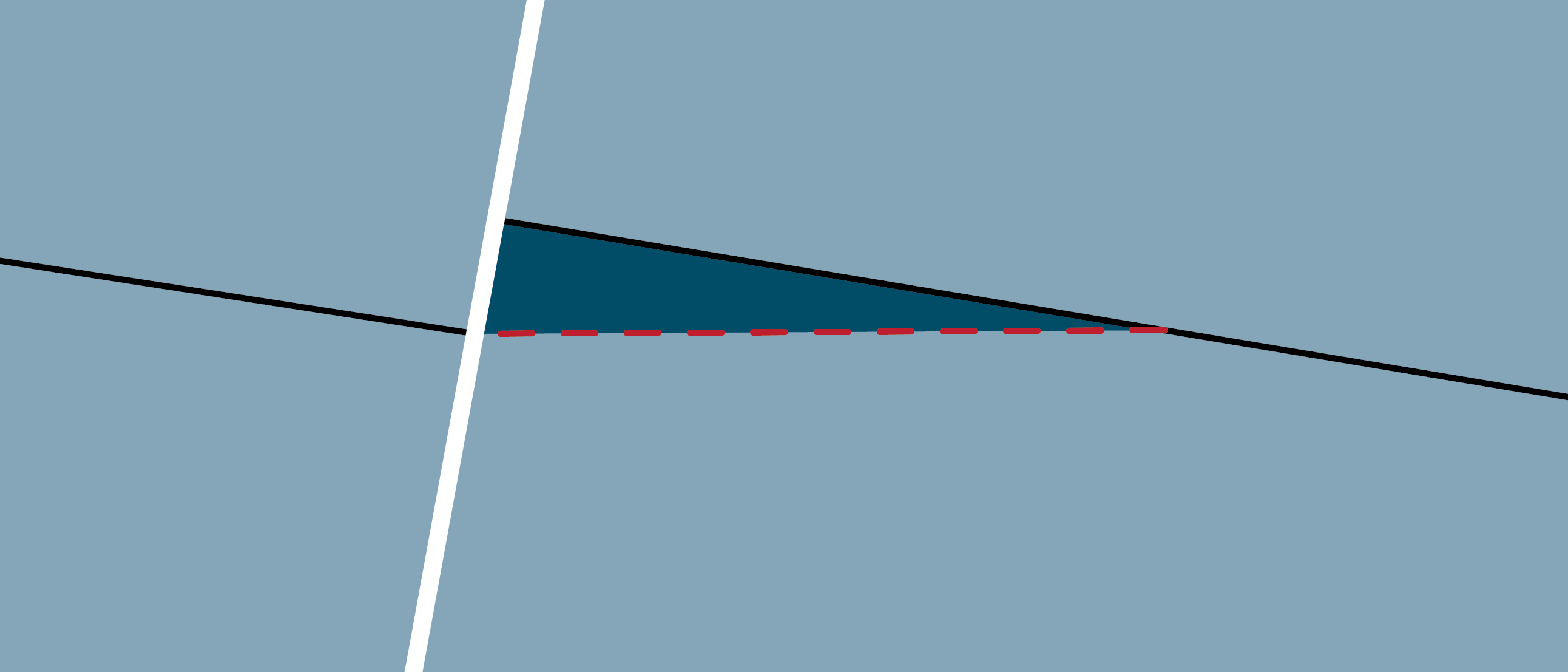

Stuart Archer from Harbour Energy commented that during his career, he had seen many cases where colleagues had been wary of allocating a probably of 1 to certain play elements in a risking exercise, even when there was overwhelming evidence from offset wells and fields that this could be done. He used the presence of the Kimmeridge Clay source rock as an example, which is by far the most prolific source across the Central and Northern North Sea. “If we know that the Kimmeridge Clay is present and we know that it is mature thanks to the production of oil from nearby fields, what is the rationale behind introducing uncertainty when it comes to source rock presence?”, he asked. “We are over-risking things and we understate the chance of success”, he added.

Exploration success vs. volume estimates

This is particularly interesting to conclude because the understating chance of exploration success seems to go hand in hand with overstating the volumes to be found. Of the twenty six discoveries presented by John Seedhouse, only four had a post-drill volume that was larger than the pre-drill estimate. This is another well-known issue in the industry. Convincing management to drill a well, especially in an international operating company where competition from exploration teams in other parts of the world is prevalent, one of the ways to get your well drilled is to be upbeat about its potential volumes.

The element I feel always gets overlooked is that we rarely drill crests, which means that pre-drill ‘Prospect GPOS’ is not comparable to post-drill statistics. That bakes in a proportion of perceived under-achievement from management when looking at post-drill stats. If we drill prospects at ‘economic threshold’ depths, then strike rate can never match pre-drill POS for a portfolio.

Bill Wilks – Merlin Energy Resources

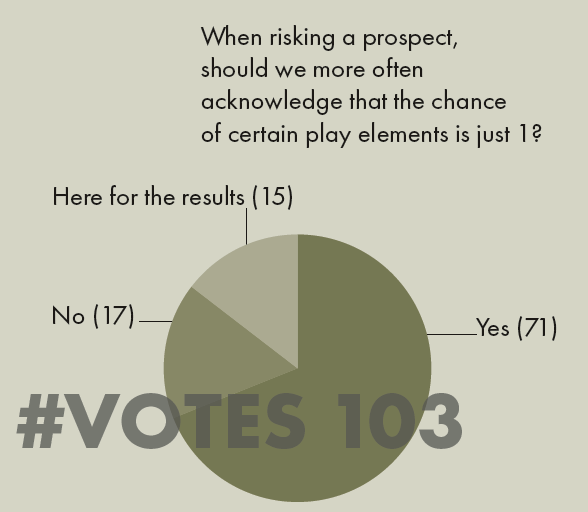

Poll results

Back to the risking element of the exploration workflow. The discussion taking place during the lecture prompted us to organize a poll along similar lines. Of the 103 respondents, 71 voted “Yes”, saying that it is justified to sometimes allocate 1 to an element in the play-risking exercise. Amongst the people who voted were many petroleum geologists as well as geophysicists, including a few from Harbour Energy. But interestingly and maybe not surprisingly either, there were also some who thought it is not done to allocate a probability of 1 in the risking process. Amongst this group were some seasoned explorers and university lecturers, so there is certainly a debate to be had still.

Debate and perspectives

And this debate unfolded in the post’s comments section, for which all contributors are thoroughly thanked.

Jan de Jager, former explorationist with Shell and also the author of another article in this section, argued that a 100 % probability for some play elements can very well be reasonable. He cites charge in some Tertiary deltas and trapping geometry for a Miocene reef as two examples. He also mentions that the reason for the failure of unsuccessful exploration wells can tell you whether a 100 % chance factor may be justified. For example, if there are no wells within a sector of a basin that has failed for the absence of charge, why then go below 100 % for a new exploration well?

Arguments against 100 % probability

“Some explorers still want to go for 99 %. After all, they then maintain, how can you ever be 100 % certain about the geology in an exploration environment?” “But that would be just a covering-your-back exercise that has virtually no effect on the final probability of success”, he argues, adding that it is well known that the average rate of success in exploration is better than the average pre-drill Probability of Success. “It may well be that a reluctance to assign 100 % probabilities has something to do with that”, he concludes.

Insights on risk precision

Rene Jonk, who worked for ExxonMobil for a number of years, commented that “Death by 0.9” was a famous saying going around the workrooms at his company. “Especially when there was a 9-element risk matrix, it was very true…”, he wrote.

“Some would argue that you can never be 100 % sure, but I think that speaks to a poor understanding of precision in risk. It’s why I tend to suggest keeping your risk number to one decimal, and hence, the “I can never be one hundred percent sure” becomes a 1 for anything from 0.95-0.99!”

“In my experience, it is more important to articulate the main reason a well will fail and what observation in the well would support your main inclination for well failure. The false precision of a risk number becomes rather meaningless when you’ve put “some risk” on every possible element. It becomes a poor predictor of well outcome. Especially when we often fail to articulate what we are risking against.”

Triple value logic

Not everybody buys this, though. Martin Jagger argued that besides true and false, the result of logical expressions can also be ‘unknown’, citing Donald Rumsfeld when he said that there are always unknown unknowns in our attempts to understand and predict nature.

“Whilst there may be a large volume of information relating to the risk or decision in question, it may be partial information, incomplete, uncertain – even conflicting – in terms of support it provides for a given interpretation. Some practitioners – organizations or individuals – are sometimes biased by over-reliance on a particular source of evidence or “belief” when faced with contradictory or equivocal evidence from elsewhere.”

He, therefore, makes a case for using evidence support logic – or Triple Value Logic – which breaks down the question into a logical hypothesis model, exposing opinions and judgements to the quality of evidence available.

Raffik Lazar from GeomodL International, with this discussion in mind, therefore argues to distinguish between exploration in frontier exploration, where a general lack of control of all play elements exists, and ILX-driven exploration whereby swathes of data are at the geologist’s fingertips. Read more about that in his column in the Insights-section.