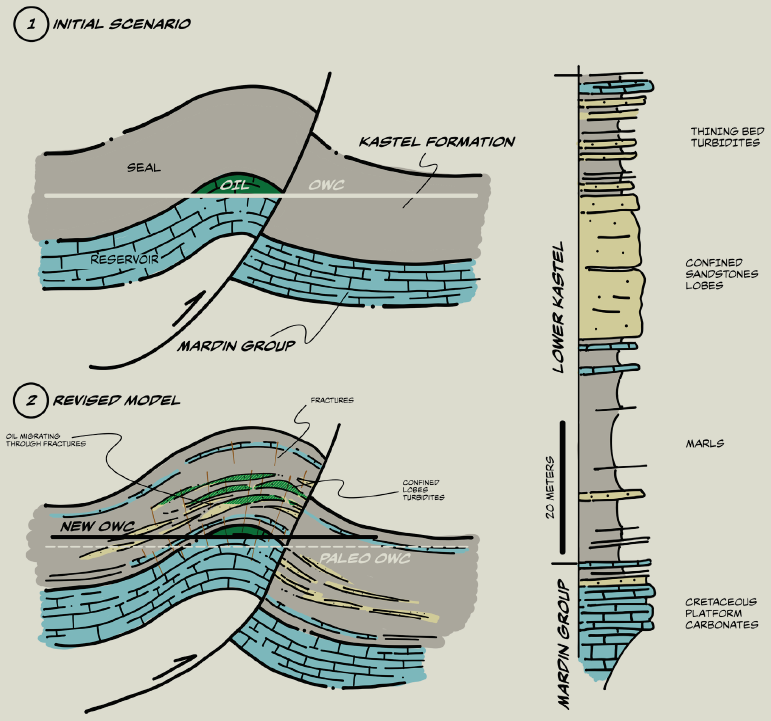

This is a story of how subsurface data was used in the way it should be – to incrementally gain a better understanding of how a petroleum system works. And whilst doing so, a much more subtle picture of a play emerged – from a binary situation of having just a reservoir and a seal to a situation where the latter is also recognized as being able to host oil.

This can either be considered a complicating factor, with oil being “lost” in thin sands within the overburden, or it can be seen as an opportunity.

Geologists from the Turkish Petroleum Corporation (Türkiye Petrolleri Anonim Ortaklığı, TPAO) did the latter, successfully, and are now producing oil from what was previously considered a unit that had to be drilled through as quickly as possible. It took 70 years of initially bypassing this interval with hundreds of wells.

Identifying the issue

But how did this all happen?

It started with the observation that development wells drilled into the platform carbonate reservoir of the Cretaceous Mardin Group sometimes had much earlier water breakthroughs than anticipated. It led to the conclusion that the oil-water contact was, in fact, at a shallower level than previously thought and that the closures were not filled-to-spill.

This was an unexpected conclusion, as the source rock in the area is regarded as prolific.

Could this be driven by oil having leaked into the overburden instead? This triggered a study to better understand the overburden.

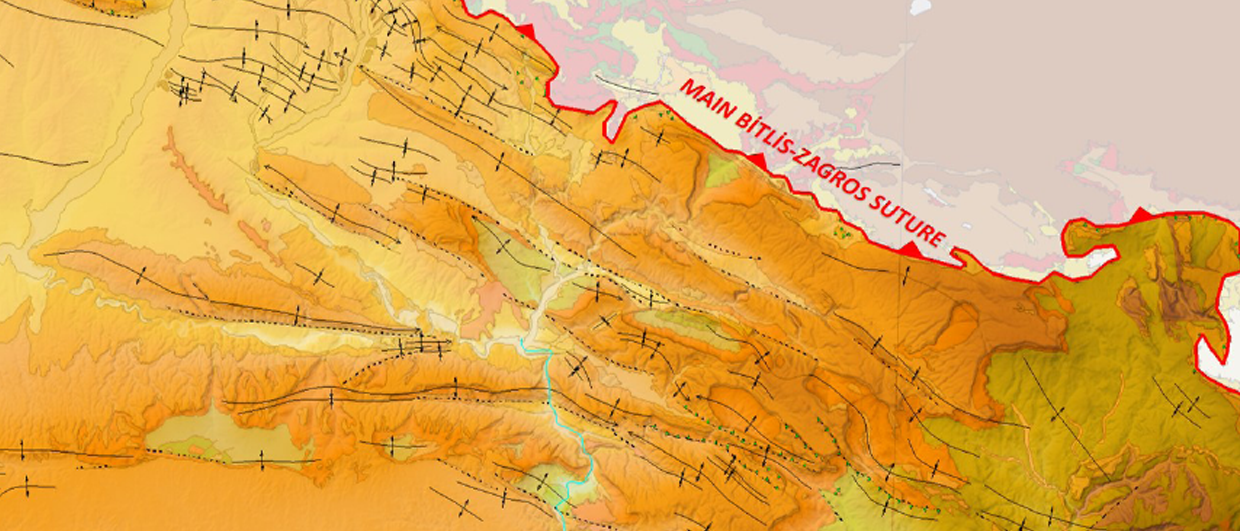

The first thing to note here is the lithological variation within the overburden. Gokturk Mehmet Dilci, an exploration geologist from TPAO who is behind initiating this study, noted that moving further away from the axis of the foreland basin that developed in southeast Türkiye in Late Cretaceous times, the percentage of calcite increases. This increase in calcite content subsequently promoted a more brittle style of deformation as compressional stresses folded and faulted the succession. It is the fractures that were generated in the overburden that compromised the seal to the underlying carbonates, promoting the secondary migration of oil.

Discovering the migration path

But where did the oil migrate to? Gokturk made another observation in the field, where he studied outcrops of lateral equivalents of the sealing units belonging to the Kastel Formation in the Adıyaman Province, Southeast Türkiye. And some of these sands, deposited as turbidites in the foredeep at the time, were oil-stained. It is the same sands that were drilled by wells targeting the deeper carbonate reservoir for about 70 years without much consideration of their reservoir potential until Gokturk and his colleagues started to join the dots that the “missing” oil in the carbonate closures could, in fact, be lurking in the turbidite sands above.

The Kastel project – analysis and development

This subsequently initiated a research project to better understand and map the Kastel Formation to see if economic quantities of oil could be produced from these turbidite beds. Could this be a hint of what is happening in the subsurface? he thought. He then embarked on a detailed study of the potential of the Kastel Formation to host economic quantities of hydrocarbons. Until that time, no or very little data acquisition had been done on the Kastel Formation, driven by the prevailing concept that it was just the seal that had to be drilled through as soon as possible. In some wells, only Gamma Ray and Sonic Slowness logs were available; in many wells, logs were missing altogether.

Under the umbrella of the “The Kastel Project” the team from TPOA performed detailed microscopic analysis of cuttings and, where available, core samples, focusing on oil indications. This information was integrated with the limited existing petrophysical data to determine perforation interval, which led to the assessment of re-entry potential for old, abandoned wells that were originally drilled with the deeper Cretaceous carbonate targets in mind.

To optimize the reservoir stimulation approach, XRD mineralogical analysis of the turbidite sands was carried out in order to better understand the response to various acidization techniques. Finally, a development design had to be put in place to isolate the perforations in the turbiditic sands of the Kastel Formation from the deeper carbonate units, which had long been invaded by water cones.

Results and impact

Out of approximately 500 wells initially screened based on sparse petrophysical logs, around 50 candidate wells were selected after detailed analysis of archived drill cuttings, resulting in nearly 30 successful discoveries through perforation and acidization.

This project led to the first-ever oil production from the Kastel Formation sandstones in 2019; 65 years after the founding of TPAO and 86 years after the establishment of the initial petroleum exploration division in Türkiye. The play is still being actively explored and drilled, demonstrating the big shift in thinking of how this petroleum system works. It is a good example of how a second look at subsurface data can result in the extension of oil production in an area beyond the boundaries of the initially defined play. In this case, by looking up.