The demand for replacing O&G reserves along with the development of modern drilling and imaging technologies has pushed the boundaries of offshore exploration to new limits. By applying data-lead concepts, the industry has been able to test high-risk-high-reward hydrocarbon plays resulting in successful exploration campaigns like those conducted in Guyana and Namibia. If we continue to follow this approach in other unexplored basins, then we can agree that the deepwater Colombian Basin is on its pathway to potentially become one of the next big frontiers.

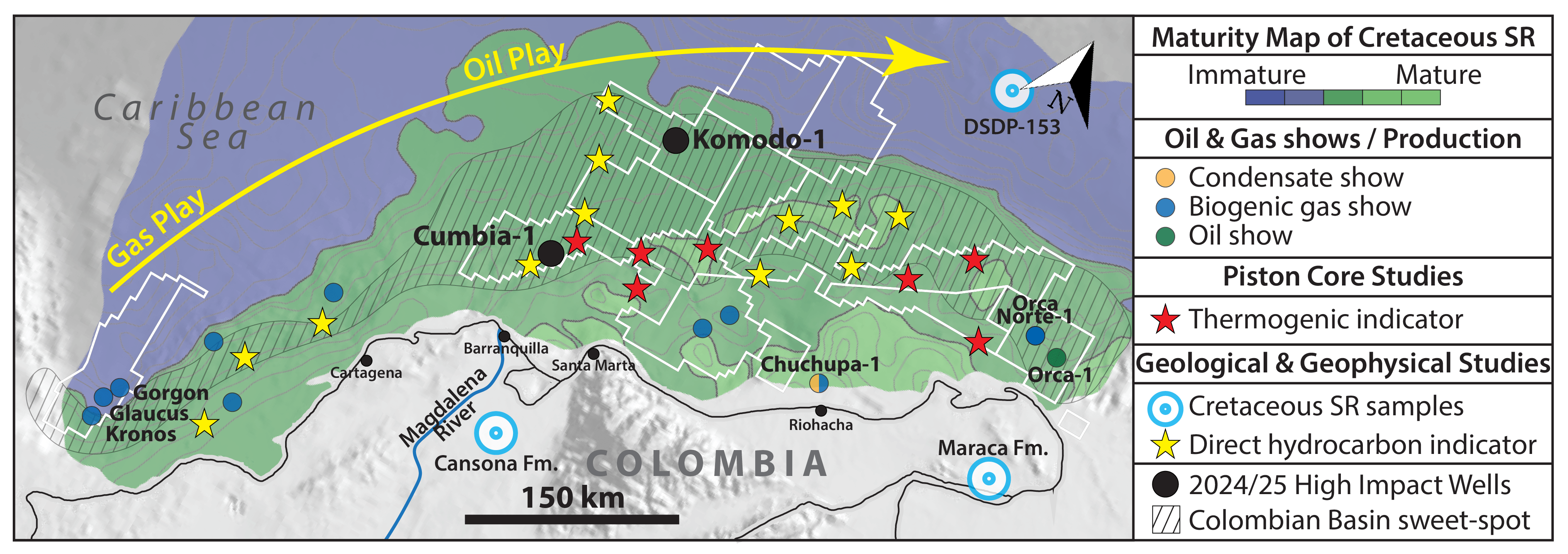

Since the first commercial offshore gas discovery made by Chevron in 1979 with the Chuchupa well, the industry has proven the presence of a biogenic gas play along the nearshore Colombian Caribbean coast (Figure 1). For the last 20 years, the O&G industry has focused its technical and commercial efforts on the exploration of deeper-water targets by drilling 11 exploratory wells until today, which has further confirmed the extension of this biogenic gas system. It is no surprise that these drilling campaigns have also brought new insights into an active thermogenic system with untapped potential in the region.

A dogma that needs to be re-evaluated

Aside from the technological challenges that O&G companies face by exploring deep to ultra-deepwater frontier areas like the Colombian Basin, we have to consider a three-decades-old geologic dilemma of two opposing models that have attempted to explain the origin of the Caribbean region. It is key to solve and understand this paradigm because it conditions the crustal architecture of the basin, and thus, the potential presence or absence of an active thermogenic petroleum system sourced by an organic-rich Cretaceous source rock.

In simple terms, the Pacific or “allochthonous” model considers that the Caribbean plate was formed in the Pacific region from a mantle plume active during Late Cretaceous times. This thickened the oceanic crust, which subsequently drifted relatively towards the east to its present-day location. In contrast, the “in-situ” model proposes that the Caribbean Plate formed in-place by the opening of the Americas since Jurassic times.

By solely favouring the Pacific model, which seems to be the preferred dogma in Caribbean tectonics, then the preservation of potential Cretaceous source rock and its petroleum system wouldn’t be possible. In turn, this would deem the area not as prospective as it could be if the “in-situ” model would be the preferred one.

A current study conducted by the Conjugate Basins, Tectonics, and Hydrocarbons (CBTH) Consortium at the University of Houston uses several newly acquired 2D and 3D seismic datasets, which has evidenced the dramatic heterogeneity of the crustal structure of the Colombian Basin. This new study challenges both opposing tectonic models to an extent that we may consider that one single model simply doesn’t fit all. Elements of both models – a hybrid model if you will – may be the way forward. Further details on this new study will be discussed in an upcoming publication.

A glimpse of the existence of an active thermogenic petroleum system

In a recent interview, top-executives at Ecopetrol stated that the 2024 Orca Norte-1 well is a “gas discovery with a different composition than what was found at Orca -1”. More importantly, it was confirmed that the Orca well “not only encountered gas, but also instances of heavy oils and crude oils”, which is currently being further studied by Ecopetrol. But, the analysis does also show that there is “an even bigger gas potential for the country.”

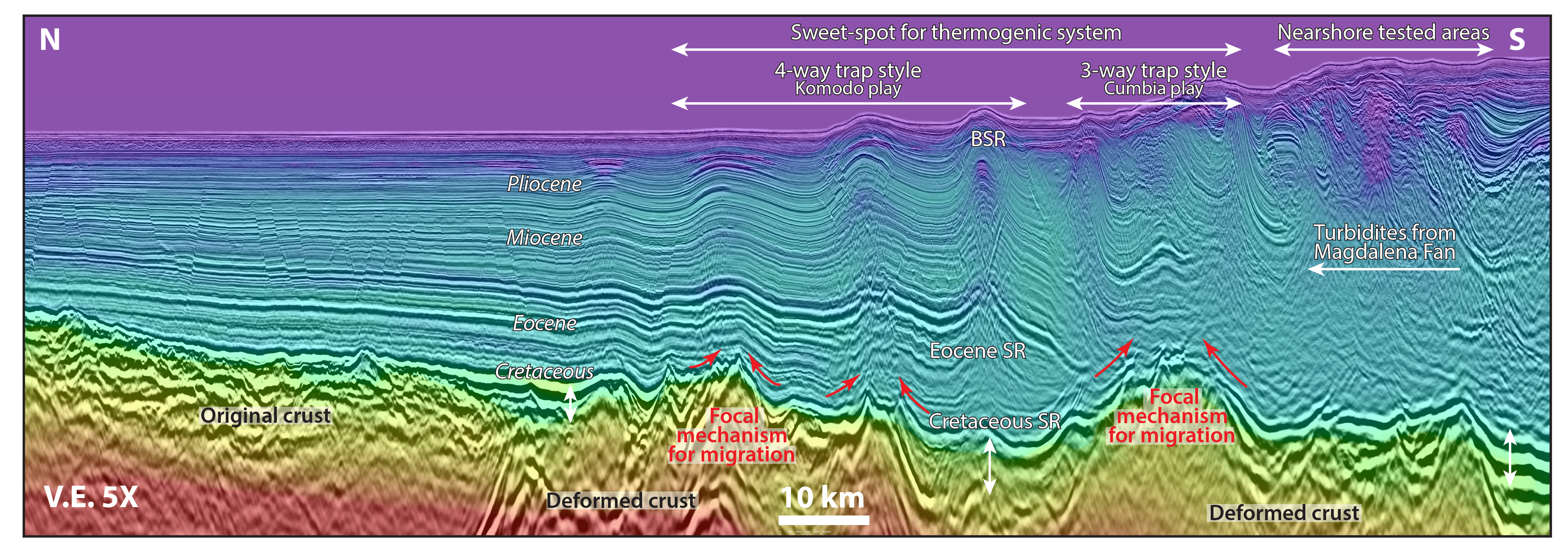

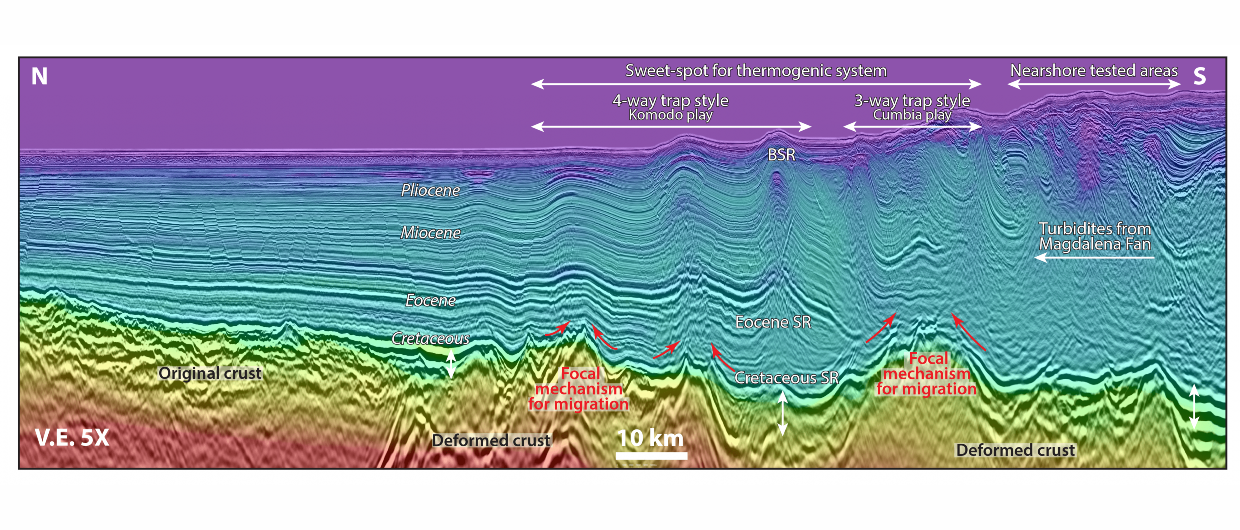

Are Ecopetrol’s comments confirming the presence of a potential thermogenic system on the Colombian offshore a surprise? Maybe not so much. Previous authors already reported thermogenic signatures on piston core studies, oil slicks, oil seeps, heavy isotopic signatures mixed with biogenic gas samples, and condensate fluids derived from early production from the Chuchupa well. In fact, Carvajal-Arenas included all previous observations and proposed a thermogenic hydrocarbon system for the Colombian Basin with mature Cretaceous (?) source rocks underneath areas like the Magdalena fan system and the South Caribbean Deformed Belt. To add to that, we believe that an active younger Eocene petroleum system could be also present in the Colombian offshore (Figure 1).

All these pieces of information seem to now be coming together, pointing in the direction of an active thermogenic petroleum system and the need to re-evaluate the prospectivity of the Colombian Basin and current Caribbean tectonic models.

A High-Impact well: It is time to go deeper

A new family of wells will be drilled in the coming months testing deeper areas of the Colombian Basin. Oxy and Ecopetrol are planning to drill the Komodo-1 exploratory in the second half of 2024. It will be the first well to drill in the Colombia ultradeep-water basin, and it will test a 4-way anticlinal structure, with class 3-AVO anomaly, conformable with structure. And last but not least, the prospect features a double flat spot. The Komodo-1 well is expected to have a water depth record of approx. 3,950 mbsl, and targets turbiditic Mio-Pliocene sandstone reservoirs (Figure 2).

Even though the Colombian Caribbean Sea is already classified by many as a biogenic gas province, let’s not forget several examples of overlooked basins that ended up yielding some of the biggest oil discoveries seen over the past few years. In Namibia’s Orange, source rock presence and maturity were continuously debated following the discovery of the Kudu gas field in 1974, until Total´s Venus giant oil discovery came along in 2022. A similar thing can be said about the now famous 2015’s Liza world-class oil discovery in Guyana, where previous wells mostly encountered heavy oil along the coast. Also, keep in mind the Campos-Santos success story, considered a gas province for many decades – just like the Colombian Caribbean offshore- until the pre-salt play was tested in 2006. With lessons like these, should we consider that the Colombian Basin is on the pathway for a big discovery?