It must have been a major exercise to write the paper that was published recently by authors Maryam Khodayar and Sveinbjörn Björnsson in the Open Journal of Geology. I know that first-hand, as Maryam told me that she needed some time to recover from pulling this project together. It is understandable – the authors reviewed and illustrated the myriad of shallow and deep conventional as well as unconventional geothermal systems that are currently either in use or are being developed.

If the overview demonstrates anything, it is that a lot is going on in the area of geothermal energy, from systems designed to operate at 1 m depth all the way to 20 km. This variety of concepts is not only a reflection of the different end-users for geothermal energy, from individual households to power plants, but it probably also reflects the ongoing race to find the most economic solution especially to tap into the deeper geothermal potential that exists at greater depths. Nobody will dispute the enormous amount of geothermal energy stored in the subsurface; the trick is to unlock it economically.

Drilling is key

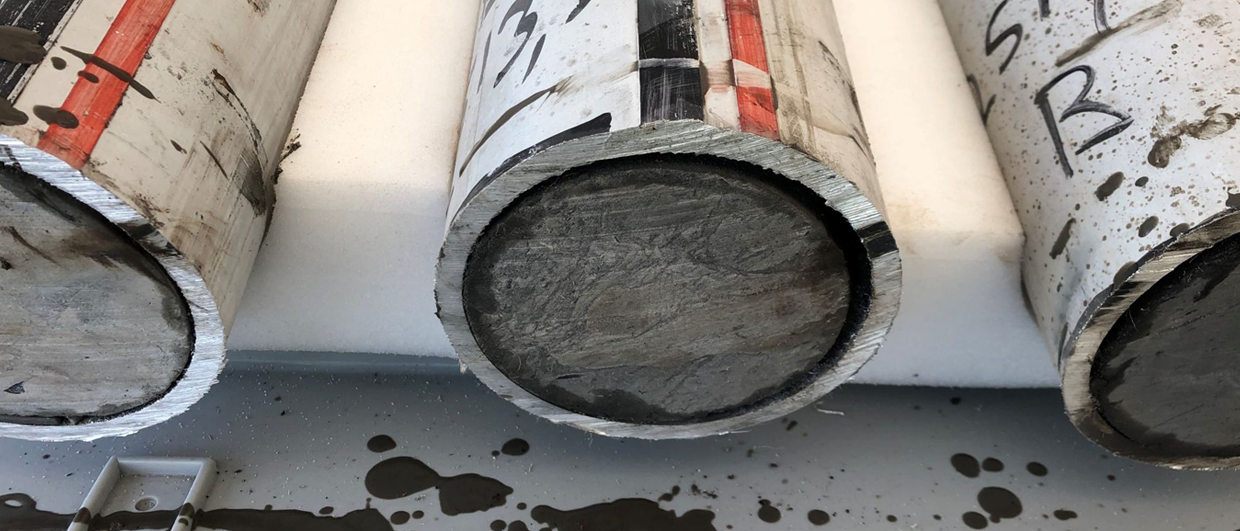

Drilling is the key factor of geothermal developments that needs innovation to complete wells more efficiently. The faster a well can be drilled and completed, be it a 200 m or 20,000 well, the more manageable the costs will be. A good example of this is the rate at which shallow loops are now being drilled in London, with its challenging geology of unconsolidated Cenozoic sediments overlying Upper Cretaceous Chalk. Some time ago, it took two days to drill a hole, now it is possible to drill two in one day. At the other end of the spectrum, a company such as Quaise is looking to drill holes of up to 20 km depth using so-called millimetre wave drilling, tapping into temperatures over 374 °C.

Confusion

Through outlining all the different ways in which geothermal energy is currently being produced as well as planned to be produced, the authors have nicely laid bare some of the confusion that often arises.

For instance, the term ultradeep is sometimes used when authors mean ultrahot. Whilst ultrahot does not necessarily mean ultradeep – geothermal energy production from a volcanic area may be ultrahot, but may not be ultradeep – ultradeep does mean ultrahot as it taps into temperatures of up to 500 °C at depths greater than 7 km.

At the same time, it is not always clear what the difference is between conventional and unconventional geothermal systems. The authors point out that conventional systems only require drilling to produce the energy – permeability, heat and a fluid are present – whilst unconventional geothermal projects require interventions to generate permeability or require adding a fluid.

In conclusion, the article is worth a read for anyone willing to brush up on their geothermal vocabulary.