It is not every day that geological expertise is brought to the Supreme Court. Late last year, Norway’s highest court dealt with a claim for compensation for subsidence damage to a detached house. The damage had occurred as a result of drilling a shallow geothermal closed-loop borehole on a neighboring property. The subsurface turned out to be key in the verdict.

The Supreme Court ruled that it was the owner and the drilling company who were responsible for the damage that occurred to the house.

The homeowners had previously lost the case in the district court and the court of appeal. The reason why the Supreme Court made a different decision regarding liability may be the expert report from the Geological Survey of Norway (NGU) on the subsidence risk when drilling in areas with marine clay.

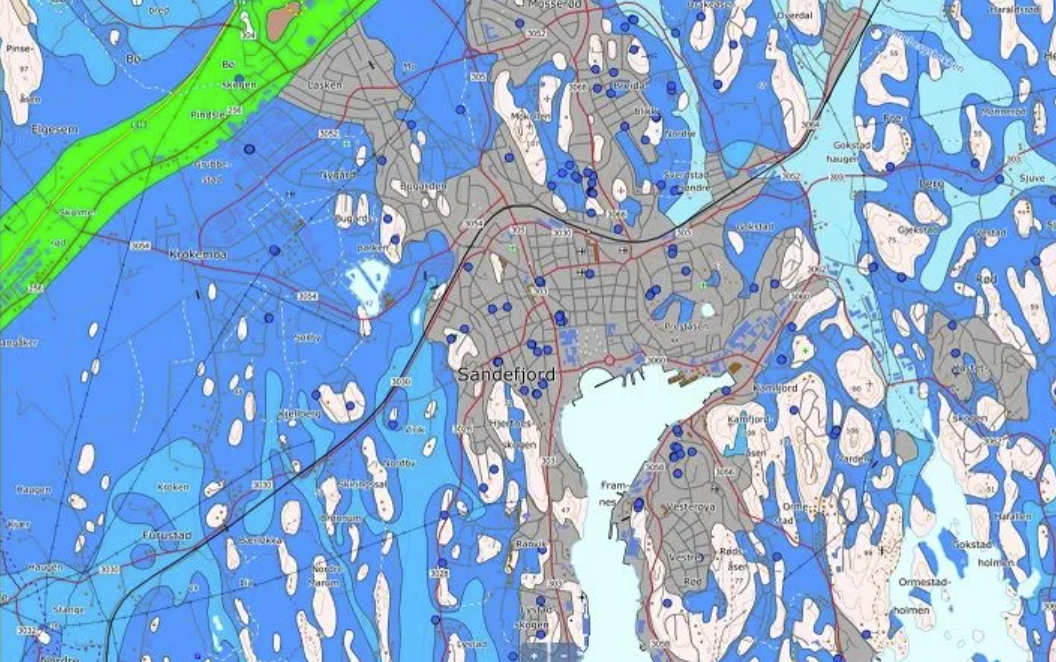

In many areas in Norway, marine clay rests directly on an undulating surface of basement rocks. Because these clays are practically impermeable, hanging water tables are frequently found. And because the underlying bedrock is often well-fractured, facilitating groundwater flow, penetration of the higher-pressure clay layer by a well can lead to groundwater making its way to the bedrock. In turn, this leads to compaction of the clay, with subsidence as a result.

Especially if houses are built partly on clay and partly on bedrock, which was the case in the example given above, differential compaction can lead to significant structural damage.

Researcher Hans de Beer from NGU emphasizes that the challenges of drilling shallow geothermal boreholes should not be overestimated, but a solid understanding of the subsurface is required.

The hydrogeologist points out that leaks can be avoided or remedied with relatively simple measures. By adding sealing compounds to the part of the borehole that penetrates the clay and somewhat into the bedrock, leaks can become a thing of the past. If the driller uses sealants that conduct heat, it can also increase the energy efficiency of the borehole.

This is not an industry practice yet, as it costs a little extra. But the price of such a measure is a fraction of the costs of leaks. “I hope and believe that this will become a standard in areas where marine clay is encountered during drilling”, emphasizes de Beer.

Many boreholes

Shallow geothermal boreholes retrieve the heat from the groundwater from a couple of hundred meters deep. In most cases, this is a closed system based on a circulating heat carrier (antifreeze) which is fed into a heat pump, before it is sent back down. Since 2020, 13,878 shallow geothermal boreholes have been drilled in Norway. The trend is increasing, and drilling is going deeper. It is therefore important that tighter regulations are put in place, not least of which require the sealing of wells.