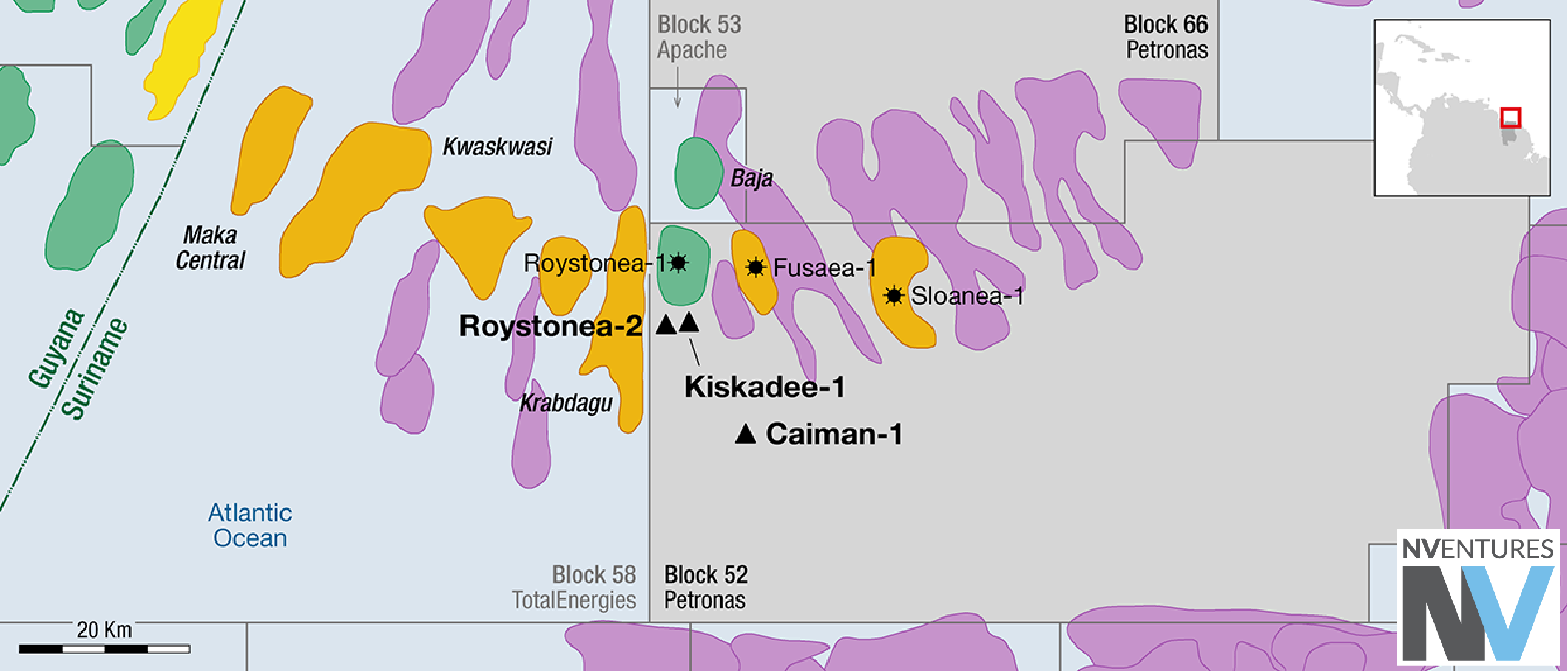

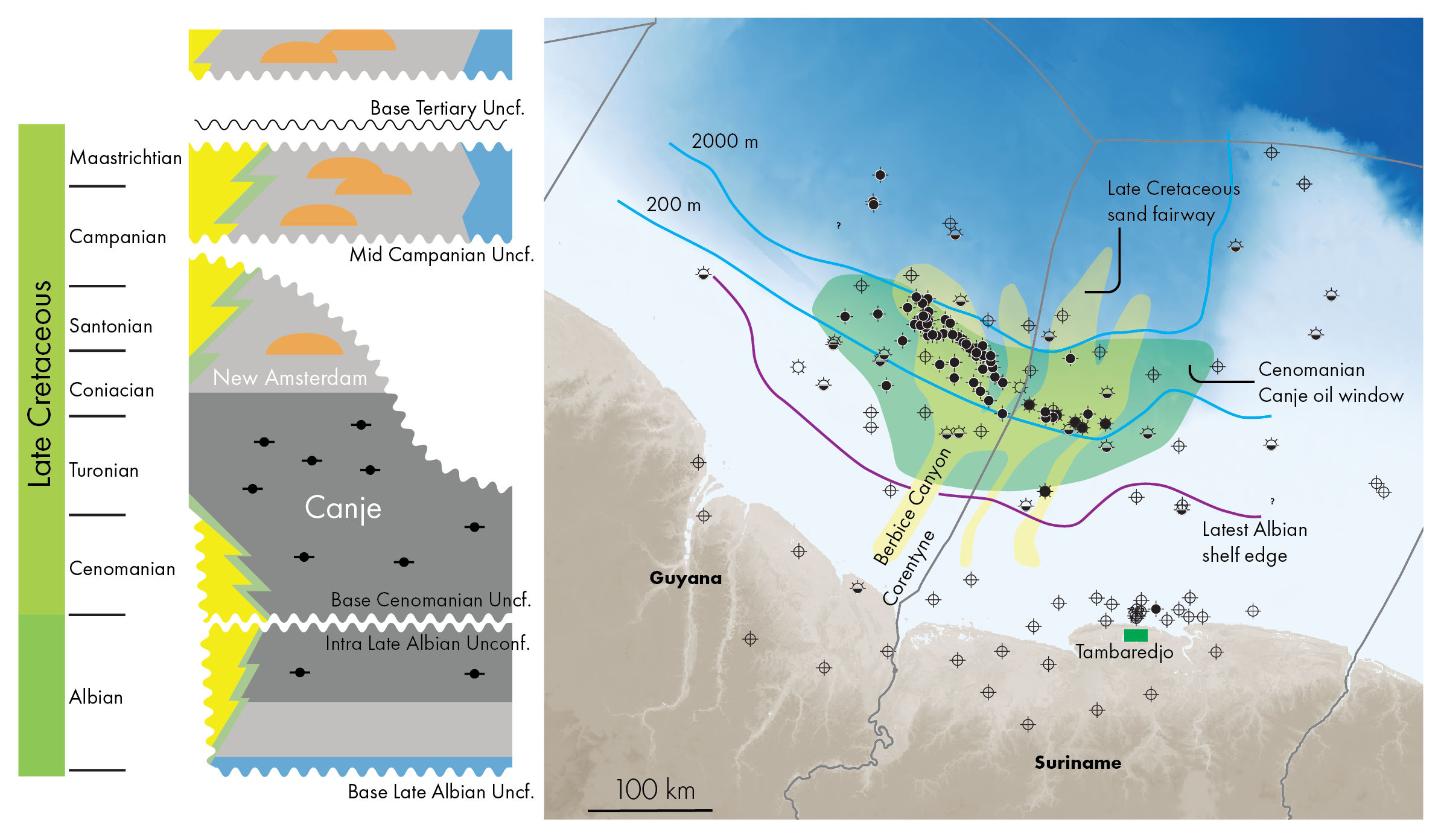

Since the prolific Cretaceous oil kitchen of the Canje Formation offshore Guyana was demonstrated by Lawrence and Bray (1989), an anomaly related to the lack of exploration encouragement away from the Corentyne region has been present (Figure 1). This picture in Guyana contrasts with Suriname where significant volumes of heavy oil were proven in the onshore Tambaredjo cluster.

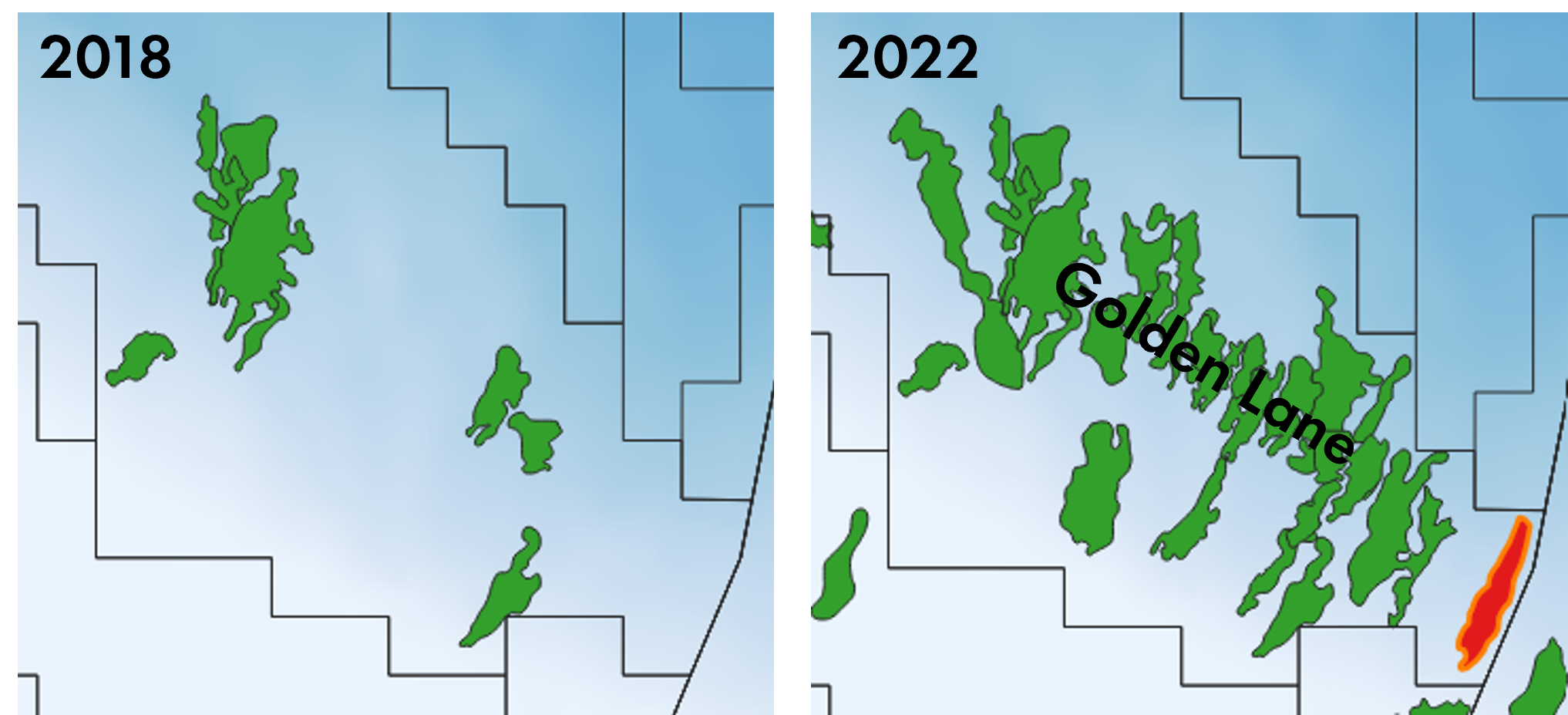

The discovery of Liza in 2015 finally demonstrated where the oil had migrated to: Lower slope stratigraphic traps. A steady flow of commercial discoveries followed the discovery of Liza, yielding a narrow northwest-southeast trend that continues into Suriname, hosting an estimated

11 billion barrels of oil. Figure 2 shows the nearly 200 kilometres of deepwater discoveries, contrasting the lack of up-dip encouragement.

An along-slope culprit?

Trude et al. (2022) found that the linearity of the deepwater Liza trend discoveries appears to be associated with sand barrier traps formed by seabed relief created by the inversion of coast parallel basement faults. This depositional pattern is further illustrated by Cronin (2021), who also indicates upslope feeder channels. For Liza, Price et al. (2021) show, using a stratigraphic slice, that a decrease in slope determines the channel-to-lobe transition.

The linearity of the deepwater discoveries evolved from a few discrete, north to north-northeast heading, channel forms into a nearly continuous, northwest-southeast orientated zone of pay sands (Figure 2) that is now collectively known as the Golden Lane. This swathe format of laterally linked fields points either to overlaps between channel-fed fan lobes or trap mergers fostered by syn-depositional contour currents.

Age-equivalent fields along the conjugate margin of Africa that were also deposited in a lower slope setting, have been demonstrated to host along-slope drift sediments. For instance, sediment waves have been observed within the Cenomanian and Albian succession of the Greater Tortue Gas Field that straddles the Mauritania/Senegal border. These sediment waves formed in lower and middle slope environments and were created by a southward flowing contour current that reworked and cleaned sands supplied to the deepwater by feeder channels.

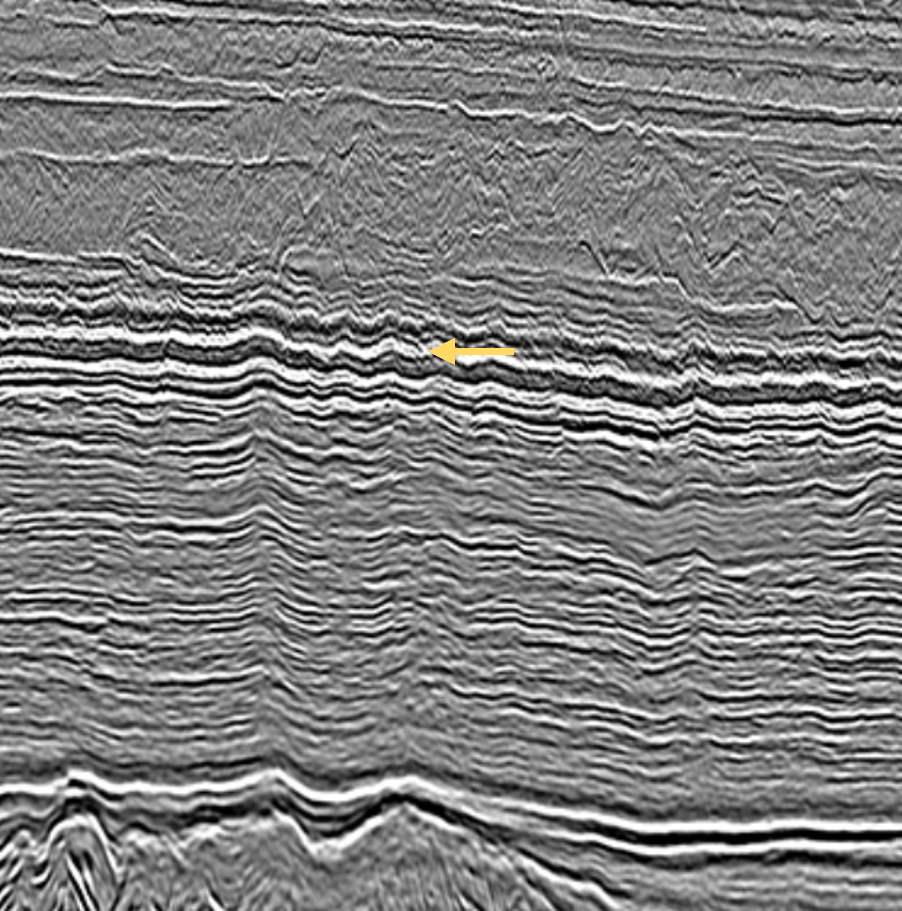

Until recently, the larger vertical scale lines required to examine bed forms did not extend across and beyond the Golden Lane. Two examples now do (PGS, 2023 and Ministry of Natural Resources, 2022). Both lines, though unscaled and unlocated, suggest that seabed waves generated by currents existed at the end of the Cretaceous (Figure 3), with the PGS line hinting that current activity commenced before that time. In addition, Nibbelink et al.

(2020) noted that dune-forming current activity commenced from the Upper Maastrichtian.

Along-slope currents and exploration consequences

With along-shore drift likely having played a prominent role in Guyana’s and Suriname’s deepwater area, the sand supply to the area could have been dominated by a single river rather than multiple smaller ones. Should this be the case, the Berbice (Figure 1), with its exit in the Corentyne, is the optimal candidate. Its history reveals a Late Albian drainage initiation, followed by the formation of the Berbice Canyon during the Coniacian. The infill of the canyon is some 2,000 metres thick and contains multiple channel-related plays.

Could the sand from the Berbice Canyon make its way to where Liza was found? A figure released by Kosmos Energy illustrates that the Berbice Canyon delivered sand through a northwest flow towards the Liza area and beyond (Figure 1). Likewise, a single dominant Santonian sand source also originating from the Berbice is illustrated by Casson et al (2021).

One dominant feeder system

What is the potential implication of one dominant sand feeder system for Guyana and Suriname’s offshore? First of all, it means that sands will

be primarily concentrated within its current lower slope trend. Furthermore, it forms a potential explanation for the lack of success when it comes to more up-dip drilling attempts: the Cretaceous sand-filled channels required to reliably supply oil from the Canje kitchen to reservoirs in shallow waters may be missing altogether.

The zone where additional prospectivity could be expected though is the upper slope and shelf edge away from the Berbice Canyon. With an active and voluminous Canje kitchen and perhaps additionally an older precursor, and the lack of onshore seeps, it is likely that more oil was generated than can be hosted by the reservoirs currently found. This was demonstrated by Tullow’s recent wells that demonstrated substantial volumes of up-dip migrated oil.

This article appeared in Issue 6 of the GEO ExPro Magazine. The PDF can be downloaded from here.