Whilst drilling of Eavor’s landmark geothermal closed-loop drilling project in southern Germany has reached the deepest point this week, the company also released a report summarising the past four years of geothermal energy production from their Eavor-Lite test site in Canada.

Eavor-Lite started producing in December 2019 and has since been running. The project consists of two vertical wells drilled to a depth of 2,400 m into the tight Rock Creek Formation. The wells are connected by two parallel laterals of approximately 1,700 m long. Fluids are pumped into one well, flow through the laterals, and are subsequently produced from the other well. Whilst doing so, the fluids are warmed up through conduction – the lateral wells have an open hole completion but permeabilities of the exposed formation are near zero.

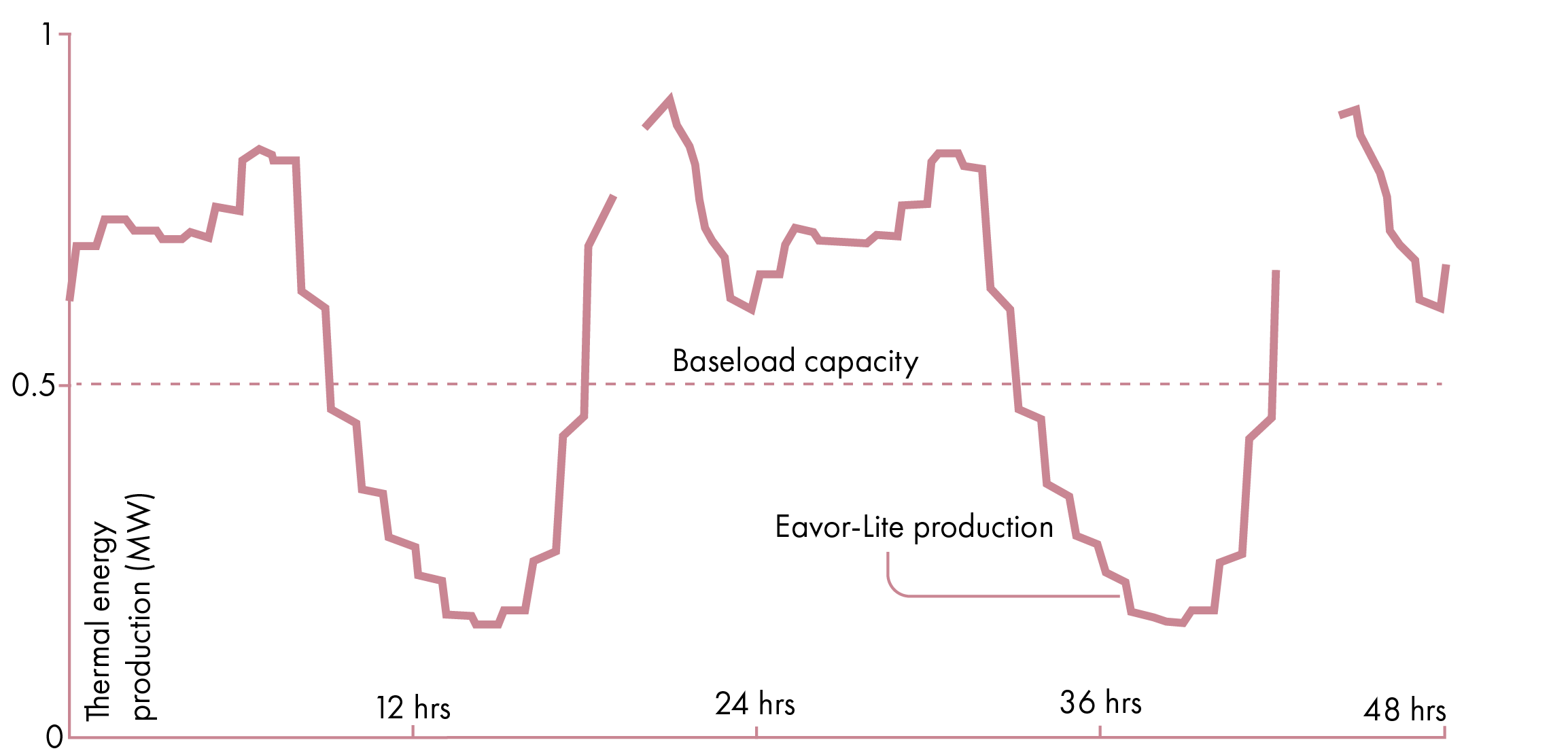

The million-dollar question now is; how much energy has the system been producing? The ThinkGeoEnergy website positively mentions 20 GWhth over the four years of operation. That sounds quite good. But when we look at the graph below, which is based on Figure 7 from the Eavor-Lite report, it appears that the 20 GWhth translates to an average thermal energy production of 0.5 MWth. And how much is that, really?

Well, it is not much. That is not a surprise of course. Heat transfer through conductivity is known to be much slower than through convection. Open-loop geothermal systems produce around 15 MW per injector-producer pair, so around 30 times more than the Eavor-Lite project. To that can be added the additional drilling costs of completing the two connecting laterals. These are not required for open-loop systems that rely on fluid migration in porous reservoirs.

At the same time, the Eavor-Lite project demonstrated system reliability with an uptime of 99.6%. Moreover, energy production can be timed to demand through the storage of heat downhole and producing it when demand is higher. In addition, closed-loop systems do not suffer from scaling, corrosion sand issues, temperature breakthrough etc, which is a significant advantage compared to open-loop systems.

But the main question is, are the costs of drilling too high for closed-loop systems to become commercial? At the moment, they simply can’t be. It is known that open-loop geothermal projects have thin margins, so with an energy production of 30 times less and significantly higher drilling costs due to the fact that laterals have to be drilled, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to conclude that this way of energy production – even though there are clear advantages to it – is still very much in an experimental phase and will no doubt need a significant technological breakthrough before this can become mainstream.