Turkey is amongst the main players when it comes to geothermal energy production worldwide, with more than 1,600 MW of installed capacity. The favourable geological setting in the Western Anatolian region is the main reason for this success. The area that is known for its extensional tectonic regime shares some important characteristics with another geothermal hotspot, the Basin and Range in Nevada, USA, where elevated temperatures at relatively shallow depths have also allowed for the development of many geothermal projects.

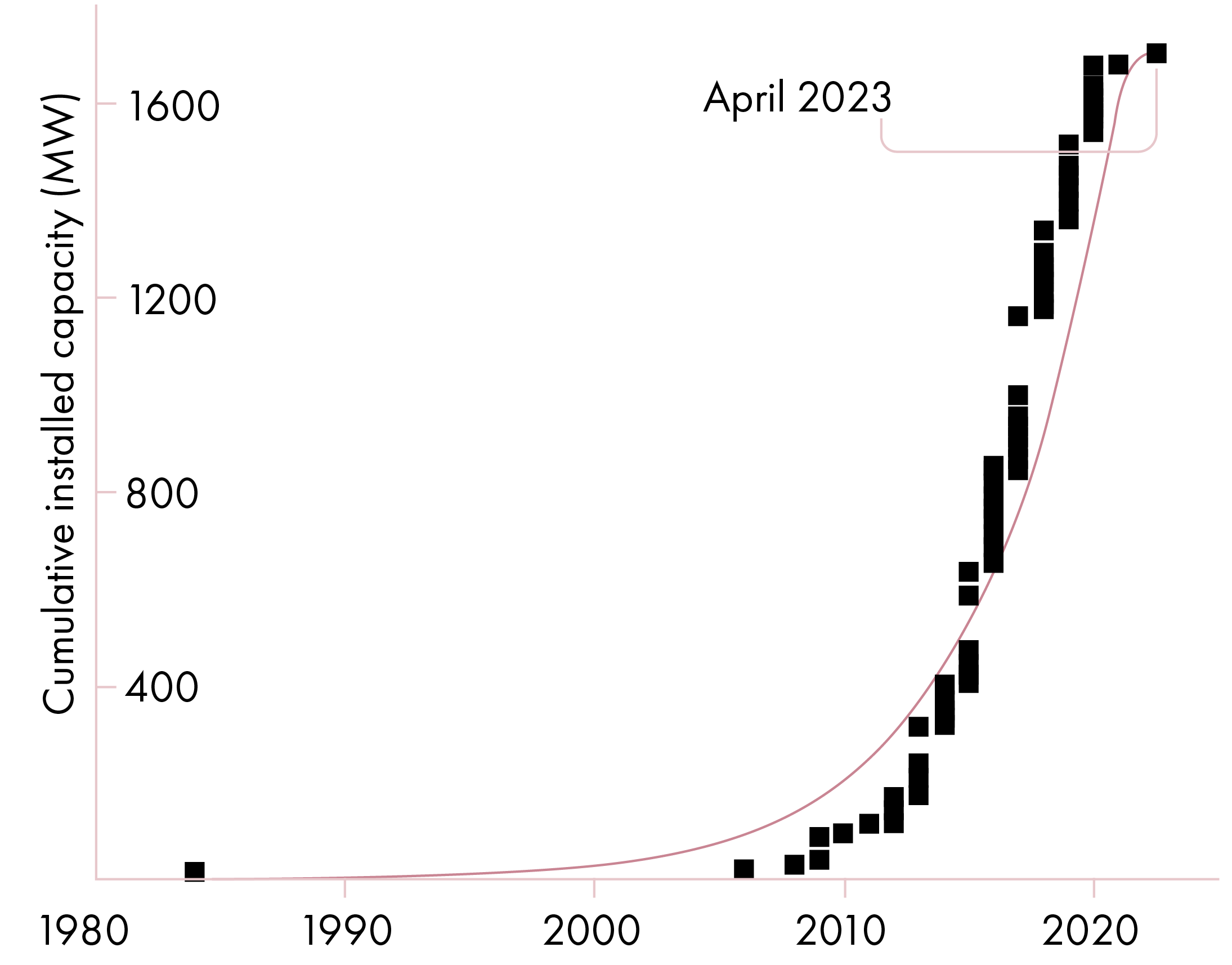

But the growth in installed capacity in Turkey has now eased. As the below graph suggests, which was sourced from a 2022 publication in the journal Geothermics by Umran Serpen and Ron DiPippo, the years between 2010 and 2020 in particular saw a rapid increase. This led to ambitions to hit the 2,000 MW mark by the end of this year and 4,000 MW by 2030. However, as the authors of the paper already conclude, with the main graben areas (see map) reaching a mature state of exploration, it will now become harder to tap into new resources if the same exploration risk profile is maintained.

Of course, there is still potential, but this will come with higher costs of exploration and exploitation. Drilling more wells close to the existing projects will only result in the risk of interference and is therefore no real solution. As DiPippo and Serpen note, there is the possibility to drill deeper, but this comes with a risk of lower permeability than the reservoirs from which production currently takes place.

It is interesting, and not at all surprising in a way, that the development of geothermal energy is showing a similar pattern as oil and gas developments in most basins. The lesson that can clearly be learned here from Turkey is that the low-hanging fruit is always developed first, and whilst that is ongoing, people without too much knowledge on the matter may be led to believe that the rate of development is set to continue in the same way. But it is not, so unless the economics change in favour of more risky drilling, it looks like the two decades of exponential growth is over for one of the world leaders in geothermal energy production.

On that basis, the authors recommend to start looking at the volcanic potential of Turkey as a way to tap into new geothermal plays.