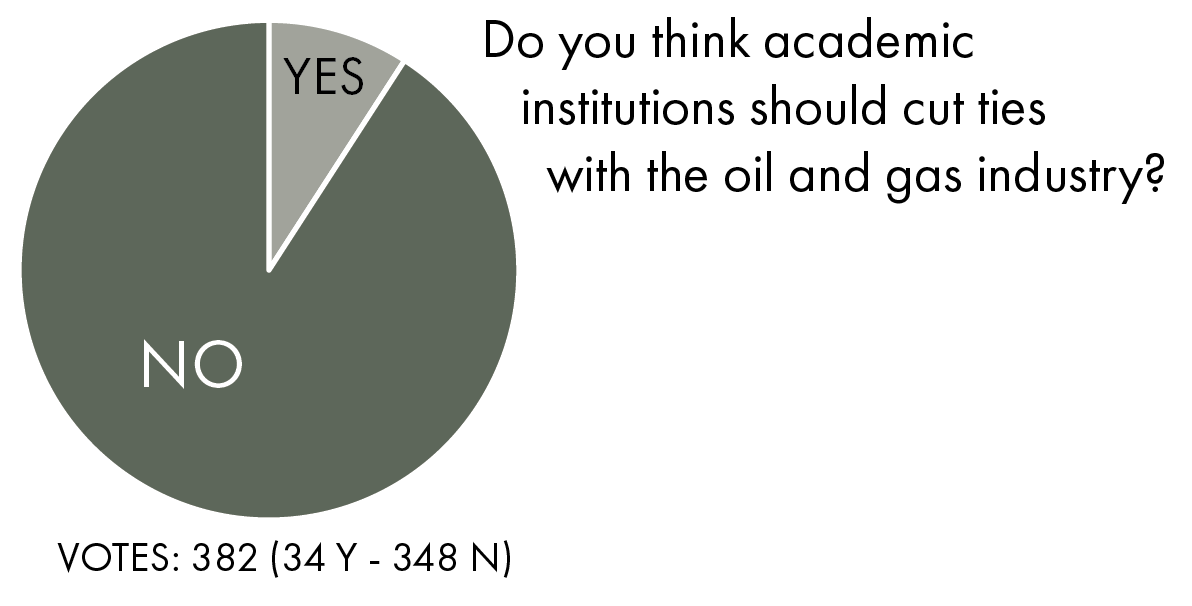

“A ridiculous question.” It was one of the comments we got on the poll featuring the question stated above. Nevertheless, we received a total of 382 votes, which is our record number when looking at the polls we have done so far. Out of these votes, a total of 91% voted “No”, so against cutting ties between the fossil fuel industry and academia.

It is probably not too much of a surprise to see this result, as our followers are for an important part people who work in the fossil fuel industry. However, looking at those who voted in favour of maintaining collaboration, there were people from academia, both senior researchers as well as PhD students and undergraduates. It shows that there is certainly a mix of opinions in the academic community, even though the mainstream media tends to mainly portray those who are strongly in favour of cutting ties with the fossil industry. And, with a few “Yes” votes from people working in the oil industry itself, there is also diversity of thought amongst those working in big oil.

Delft

One university with an active debate on whether to continue receiving money from the oil and gas industry is Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. We asked Associate Professor Applied Geology Hemmo Abels for his thoughts.

…it is too little and it is getting too late. More needs to be done, and soon.

– Hemmo Abels, Delft University of Technology

“I’m fully aware of the complex situation when it comes to societal dependency on fossil fuels”, Hemmo said. “However, we see that until today the fossil fuel industry invests a fraction of its profits into researching and accelerating the energy transition. It is too little and it is getting too late. More needs to be done, and soon.”

“Money from the oil industry can help facilitate fundamental research into green energy for sure, but the question to many is whether the involvement of universities in oil and gas research will prolong hydrocarbon use rather than speed up the energy transition.”

“On another and more practical note”, Hemmo continued, “we are receiving increasing levels of funding through the government that is focused on the energy transition. It takes away the need to accept funding from oil and gas for the science we do. At the end of the day, we as a university are limited in our human resources when it comes to performing research. That brings us to the question, is it still ok to accept money from hydrocarbon companies? Maybe not.”

The situation in Delft is particular. Even when a company such as Shell will not be able to sponsor research at Delft University anymore, the operator will still have a presence at the university through their majority share in the deep geothermal project currently under development at the university campus.

“This makes the discussion even more precarious as major hydrocarbon companies obviously start to invest more in sustainable resources. Is the investment greenwashing or indeed the serious and needed move to green energy? The wish of some to ban all hydrocarbon companies from our university becomes much less easy to answer this way”, Hemmo admits.

Sedimentology and Indonesia

PhD student Enry Horas Sihombing, who voted in favour of preserving ties between industry and academia, works at Bergen University In Norway. He recently attended the SEPM Bouma Deep Water conference in Utrecht, the Netherlands.

Enry wrote: “One professor from Utrecht University mentioned that he is currently facing a dilemma because the university is hesitant to accept funding from oil and gas companies. However, most research in sedimentology is funded by the oil and gas industry. And even though deep-water sedimentology has applications beyond oil and gas, such as underwater cables, microplastics, and more, the oil and gas industry is still the main driver and financial contributor in this field.”

Enry, who is from Indonesia, continues in an email: “Indonesia is the second-largest producer of geothermal energy in the world, but the non-competitive electricity price makes this industry unattractive and unprofitable, resulting in a low demand for geologists. The state’s electricity monopoly determines the price, which makes it difficult for the industry to do massive hiring.”

..in Indonesia, the number of students is increasing, and research is still heavily funded by earth resources-related companies.

– Enry Horas Sihombing, Bergen University

“If we relate this to academia, most geological research in Indonesia is focused on oil and gas, and coal. These industries still play a crucial role in many people’s lives, including the 3000-3500 geologists produced by these universities each year. At the SEPM Bouma conference, many were disappointed to learn that the number of geology students in the West has dropped dramatically. However, in Indonesia, the number of students is increasing, and research is still heavily funded by earth resources-related companies.”

So, if asked whether research should still be supported by the oil and gas industry, Enry reflects: “Well, because the initiative in the West is now focused on renewable energy, it’s okay to abandon funding from oil and gas. However, in terms of size, sometimes we forget that in developed countries, energy transition is still far behind, and we are still at the stage where all funding comes from oil and gas. This may be similar to what happened in Europe 10-20 years ago when companies raced to provide funding to universities.”

Reflection

Whilst concern regarding the pace of the energy transition is understandable, it seems that universities’ ability to cut ties with the fossil fuel industry is also a matter of money. Increased levels of funding from governments, at least in the West, combined with smaller numbers of students signing up for a degree in geosciences, make it easier for academia to conclude that oil money is no longer needed.

This situation is entirely different in countries like Indonesia, where student numbers have increased in recent years and where the government may not have a similar financial capacity to fund more research into the energy transition.

But the question remains; should a university turn down funding from the oil and gas sector regardless of the financial situation it is in? If so, that would then leave academic research to be more dependent on the state. But does that mean there is more academic freedom? In a way, it’s not, because government funding preferentially goes towards those topics that are deemed impactful and relevant to society. Whilst that is not wrong per se, it has the potential to undermine scientific freedom where a scientist might be unable to perform her or his research because it is not fashionable, or simply does not come with the potential “impact”.

In a way, one could argue that funding of scientific research should not come with any strings attached and left to the researchers themselves to find the most relevant and pressing scientific problems to solve. That is not the way things work these days, as a researcher in biology recently described to me: “In order for proposals to be granted, we need to involve as many partners as possible to increase the relevance and impact of our research. This includes involving companies. It is being seen as critical.”

If it is key to involve industry to win academic research grants these days, would it not be odd to exclude the industry that is responsible for delivering more than 80% of societies’ energy demand?

Why would an oil company support research? Partly because it wants to produce more efficiently, which only has a positive impact on CO2 per produced barrel. But, on the other side, research will also be funded to potentially find more hydrocarbons. It is a difficult call.

In summary, it is clear that where universities in the West may have more flexibility to fund more research into the energy transition and therefore cut ties with the oil industry, that does not mean countries in other parts of the world will be able to do the same. Moreover, one should also ask the question if research funded with a more politically-driven agenda is always ideal and properly reflects what society needs most. Let the big questions dominate the scientific discourse, which is not only how we transition away from fossil fuels, but may well require an element of how the remaining reserves are being produced as efficiently as possible with the lowest CO2 footprint.