“We need minerals to succeed with the energy transition. Today, resources are controlled by a few countries, which makes us vulnerable. Seabed minerals can become a source of access to important metals, and Norway has a sound basis for being able to lead the way and show what it means to manage such resources in a sustainable and responsible manner”, said Oil and Energy Minister Terje Aasland.

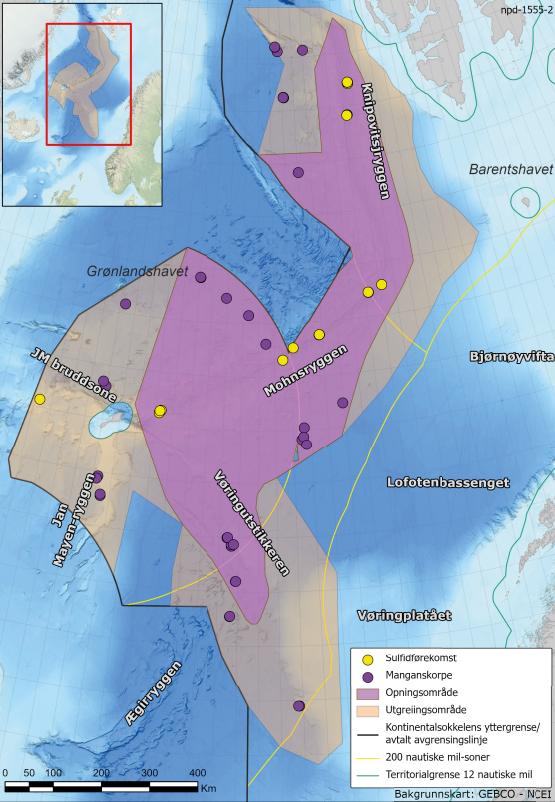

On Tuesday 20 June, the Ministry of Oil and Energy (OED) presented the long-awaited report to the Norwegian Parliament – Storting. The plan, which is yet to be approved, is to open up mineral operations within an area of 281,200 km2 in the Norwegian and Greenland seas.

In this area, which includes the Atlantic spreading ridges, mineral resources in the form of massive sulphide deposits and cobalt-rich crusts have been found. However, Aasland was adamant that more knowledge is needed before extraction can take place, something that also emerged from several other studies.

Only with data

“We currently have limited knowledge of the areas in the deep sea where the resources are found. I strongly believe that if the industry demonstrates resources they believe they can extract profitably, then it will be possible to produce these resources sustainably and responsibly”, Aasland added.

Not everybody believes that the resources mapped on the Norwegian Continental Shelf so far are worth chasing.

In a popular Tweet posted last week, Joanna Ponicka from Equivest showed data from the Loki Castle site to illustrate that the copper grades of seabed sampling campaigns are not too impressive – with very few samples having more than 1% Cu. Also, she noted that sampling was not performed randomly, with the “best sites” visited preferentially.

When it comes to Rare Earth Elements, Li, Ni and Co, Joanna is not very upbeat either: “Well, the truth is there is very little of other metals in the collected samples. Nothing else has any economic grade”, she writes. “So, basically this is 0.5-1% Cu grades on average. Mined grades will likely be lower due to selective sampling.”

Joanna continues her thread arguing that deposits of similar grade onshore need tens of them being situated close to each other to make an economic case. Given the more challenging conditions at which the Loki Castle deposits are found, she adds: “Struggling to find a basis for scientific or economic decision here…. Open to change my mind – but only with data :)”

Ronny Setså, editor of the Geo365 and geoforskning websites and who is closely following developments in deep sea mining, was quick to respond.

“In fact, Loki Castle is not the most attractive target”, Ronny writes in a message. “Yes, grade is key, and we need to see more consistently high grade samples on the NCS, but Loki Castle is an active vent and it is an axial deposit, which tend to have lower grades than flank deposits. For instance, the Fåvne flank deposit has got copper percentages more than 3 times as high as Loki Castle.”

This article published in February this year supports the higher copper grades in some of the Fåvne samples.

Step by step

“By making it possible for commercial actors to search, you will get more data collection and more comprehensive knowledge acquisition”, says the report that was sent to parliament.

The process of opening up and allowing exploration to begin will not be a fast one though. Following a decision on opening, the ministry will initiate a process to award exploration permits. In this process, the exploration companies can provide input on which areas they wish to search for. The announcement of areas for exploration will take place in stages, i.e. only smaller areas will be announced at a time.

The ministry also points out that an opening does not automatically lead to recovery. Extraction will only be possible if the governing authorities receive applications that satisfy the requirements that have been set and extraction permits are granted.

An extraction permit can only be approved if the exploration companies prove that the extraction can take place in such a way that the environment, safety and possibly other businesses are taken into account.

More concretely, the exploration companies must carry out an impact assessment as part of a plan for recovery. The government points out that these processes will provide a great deal of knowledge acquisition about local conditions.

In addition, it will not be possible to obtain an extraction permit for active hydrothermal sources, and these will be protected so that they cannot be damaged by activities in adjacent areas.

A unique position

Norway is in a unique position to be able to develop a new industry on the Norwegian continental shelf.

- The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate confirmed earlier this year that there are large mineral resources on the Norwegian continental shelf. Several of the metals in question play a key role in the energy transition and the electrification of society.

- It is is a world leader in offshore oil and gas technology and expertise, and much of this is transferable to the emerging seabed mineral industry.

- The country also has a world-leading processing industry, which can potentially contribute to the refining and the use of deep-sea minerals as an input factor on land (for example, battery factories).

- There is significant infrastructure on land and at sea that is relevant to the research and development of a deep-sea mineral industry. It includes several research vessels, Hugin AUV, Ægir ROV, Ocean Laboratory (SINTEF and NTNU), NTNU’s recovery laboratory, ReSiTec’s metallurgical laboratory and an observatory at Mohnsryggen (UiB)

- A seabed mineral law is in place for several years. Given that parliament agrees with the government’s proposal, there may soon be a licence round where companies can apply for areas for exploration.

The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate’s assessment of deep-sea mineral resources is only one part of a more time- and resource-consuming exploration and mapping process. As of today, the number of sulphide and crustal deposits is yet unknown. Those that are and will be detected still need to be studied and sampled more closely before the tonnage and grades can be determined with high precision, which is necessary to be able to determine economically drive value.