When it comes to finding new oil and gas fields, there’s not much that can beat the excitement of frontier exploration. Drilling wells in areas where no one has gone before always results in a lot of speculation and presentation of multiple geological scenarios, while eagerly awaiting the results that may or may not be directly announced.

Companies involved in frontier exploration – especially offshore – are the ones with deep pockets. That’s why it is only the majors taking on the risks of going to unprospected places. Within these companies’ headquarters, teams are always working towards ranking their global prospect portfolio such that only the most attractive ones will ultimately be drilled.

But let’s turn this picture around. How does a country attract a major to drill a frontier well? On a global scale, there are always multiple bid rounds running at the same time, with all these jurisdictions promoting their open acreage with the aim to get as many interested parties as possible. In that light, BP’s Ephesus exploration well which was recently spudded in Canadian waters is a good example to take a further look at. These wells do not pop up all of a sudden. Years of work went into what is now a potential find that may result in the deployment of 3 to 4 FPSO’s in case the well is successful.

Where to start? Not with BP, but with the Oil and Gas Corporation of Newfoundland and Labrador (Oilco), Canada, whom we caught up with at BEOS in London in April. Geophysicist Victoria Mitchell and Managing Director Jim Keating shared the story on how they have been able to attract majors to their offshore space. Not only through a lot of work and capital spending, but also through having a vision.

Mature areas

“When looking at our offshore area, only a fraction of it is what we call mature in terms of hydrocarbon exploration”, says Jim. This is the Jeanne d’Arc Basin, situated around 340 km to the east of Newfoundland. The basin hosts the only four producing fields of the entire shelf and has been explored since the 1980’s up to recently.

Apart from the Jeanne d’Arc Basin, most other areas of the enormous continental shelf that measures 200,000 km2 remain underexplored until today. “Yes, there was quite an extensive period of drilling activity in the 1970’s and 1980’s, with many of the shallow parts of the shelf tested by the drill bit, but especially the deeper parts remain largely undrilled until today”, adds Victoria.

Seismic surveys

“So, at some point in the mid 2000’s, people in the government asked themselves how to attract interest from the majors,” Jim continues. As a vehicle to start promoting the acreage and come up with a strategy of licensing rounds, Oilco was formed in 2007 as a subsidiary of an energy utility company where 97% of the energy stream is based on hydropower. “In a way, we copied the Norsk Hydro model and became a mini-Statoil”, Jim adds.

“One of the first things that came to mind was the acquisition of new seismic data”, Victoria says. “In 2011, the first 2D survey was acquired by a consortium of PGS and TGS, and using a multi-year strategic and methodical approach in data acquisition, we have been successful in imaging the slope to deep-water along the entire margin.

..it was transformational in terms of our ability to map a total of around 700 prospects and leads.

The acquisition window was limited to the May to September timeframe due to ice and weather optimization. Yet, an extensive grid of 5 by 5 km lines was the result of this project. “But, says Jim, at some point we also realised that companies not only want 2D seismic lines. 3D is what really matters these days. Ideally, this further de-risks areas and shortens the time between licence award and drilling activity.

“So, we started also doing that, with the first 3D survey being acquired in 2015. And it was transformational in terms of our ability to map a total of around 700 prospects and leads. It was certainly the trigger for the interest that we were soon to experience, as we identified that about a dozen of our biggest mapped prospects, with reserve potential over a billion barrels each, were sitting in unlicensed areas.”

Open door policy did not work

How to handle such a vast amount of seismic data, together with all the studies that had been performed at the same time? Seabed sampling and coring, biostratigraphic analysis and basin studies are just a few of the things that were also extensively worked on.

“The be-all and end-all is that we concluded that just relying on an open-door policy was not going to work”, Jim says. “There is just too much for companies to absorb and we decided that we needed to present the areas in a much more manageable way for exploration teams to handle. As a result, we shared our ideas with government and the regulator and soon, The Canada-Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Board moved to a scheduled land tenure system where smaller parts of the margin are offered as part of consecutive licensing rounds.”

It felt as a proof of concept for us.

And it worked. Exxon was the first to bite in 2015. “It felt as a proof of concept for us”, adds Jim. “The availability of 2D and 3D seismic has been instrumental in successful land sales even in times of low commodity prices. Since 2015, the region has garnered over $4 billion in work commitments from exploration companies.”

By 2018, up to 14 companies had made bids for acreage, with over half being new entrants to the region. Because the licensing term is 6 years with a possible extension to nine years, and companies tend to wait and see what their neighbours are doing, the drilling rigs did not pour in right from the license awards. “That’s the phase we are at now, following some licence extensions a couple of years ago”, Jim says. “And yes, there were some uncertainties around offshore regulations that had to be ironed out too”, he adds.

But, here we are in 2023, and there is the possibility of more than just the Ephesus well being drilled. An Exxon-led group will namely spud the Gale well in the Jeanne d’Arc basin north of the Hebron and Hibernia platforms.

Different times

“Let’s face it, oil is not a popular word these days”, Jim continues. “And while equity participation in offshore oil developments has delivered significant returns so far to the state, it also entails significant risks and continued investment levels that a small province may not be well suited for.” Whether or not the provincial Newfoundland and Labrador government wants to continue to have an active stake in oil and gas developments is something that is currently debated,” Jim concludes.

“It’s uncertain times in that respect for OilCo, but we are tremendously proud of what we have done the past 15 years in creating value and investment for the province. We are now entering an important and possibly final chapter of our story where these most interesting prospects identified nearly a decade ago are now being drilled. It’s exciting times ahead when it comes to the two drilling campaigns that will unfold this summer.”

This is why Ephesus is a well to watch

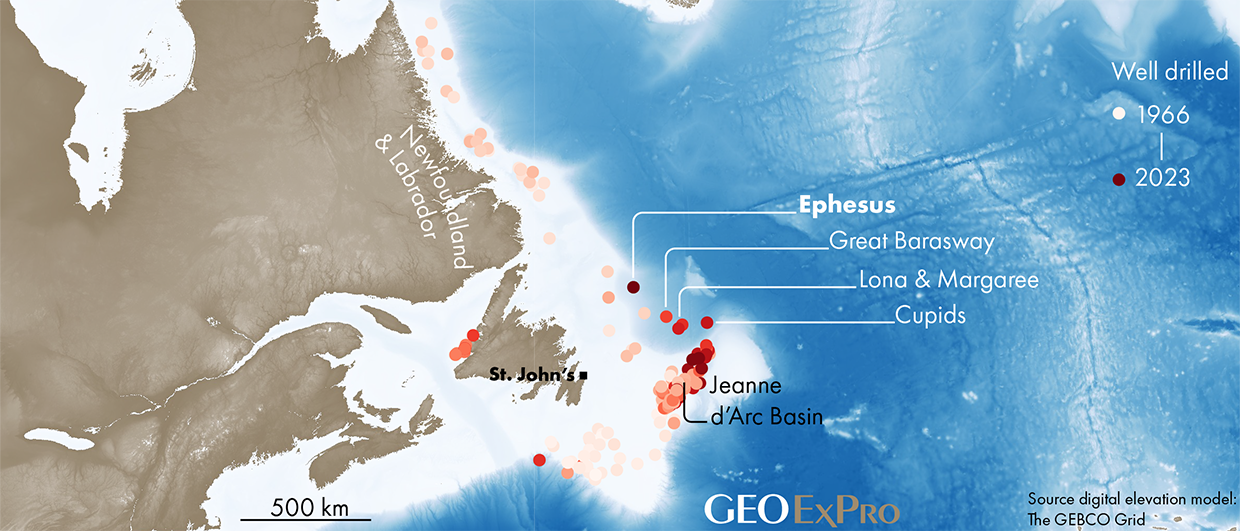

Looking at the year exploration wells were drilled along the Newfoundland and Labrador shelf, it is clear how much of a frontier well Ephesus is.

We plotted the exploration wells drilled on the Newfoundland and Labrador shelf on a bathymetric map and colour-coded the wells to the year they were completed. A nice picture emerges as a result.

First of all, it is clear that early exploration focussed on the shelf areas only. But, despite being limited by water depth, the geographical distribution of wells is quite impressive. Then, from about the mid-1980’s, a geographical concentration of drilling takes place into the area of the Jeanne d’Arc Basin, where the only currently producing assets are located.

Chevron is the first company that moves to deeper water in 2007 through drilling Great Barasway, followed by Lona (Chevron) in 2010, Margaree (Chevron) in 2013 and Cupids (Equinor) in 2015.But now, BP will move even further away from the Jeanne d’Arc Basin, with Ephesus being even further to the northwest in around 1,300 m of water, testing an Eocene deep-water sandstone target.