At the terminus of every major river is a major delta, and these large sedimentary depocentres invariably host prolific oil and gas basins. While the Mississippi, Congo, Nile, and many others around the world have been, and are being, successfully explored and developed, the vast Orange Basin offshore South Africa and Namibia has only recently started to reveal its enormous potential.

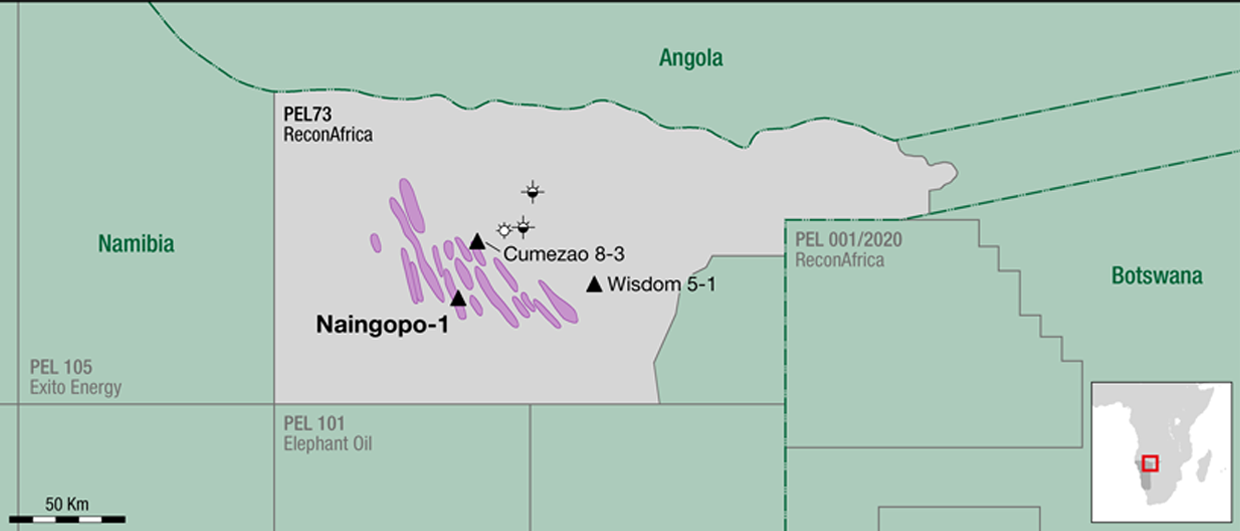

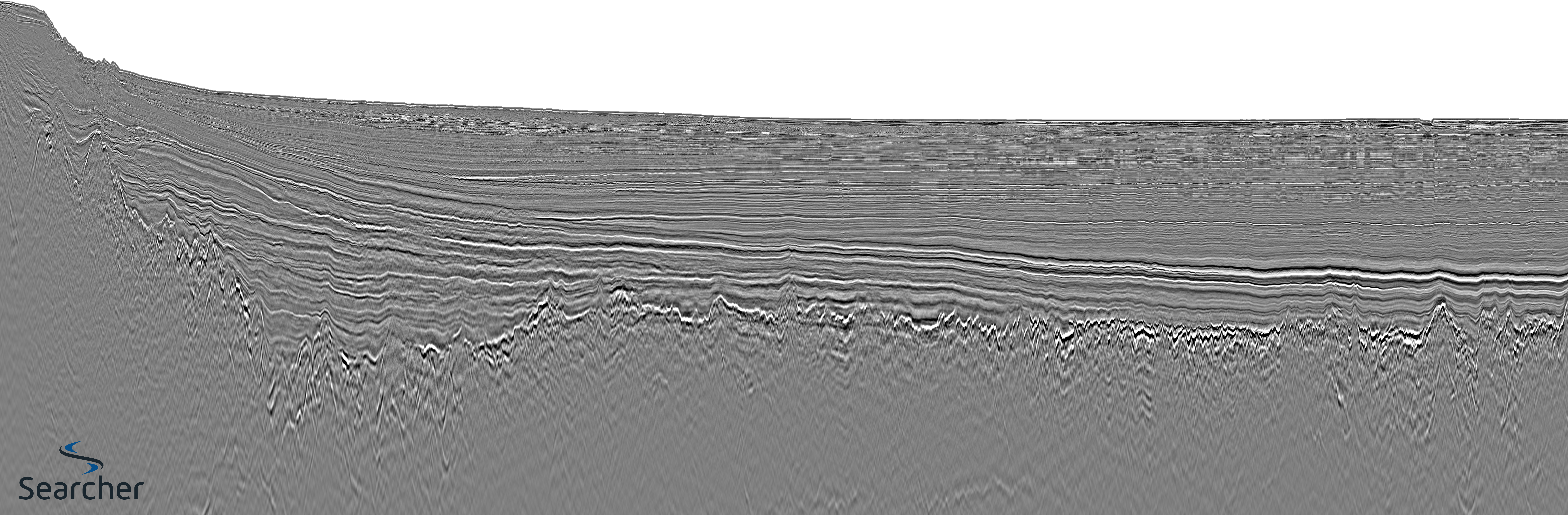

The Orange Basin hosts over 7 km of sediment, delivered there throughout the Cretaceous from the Orange and Olifants Rivers. It extends from the Luderitz Arch in Namibia to the Agulhas Fracture Zone in the south of South Africa covering an area of about 160,000 km2. The structural setting is a rifted-volcanic passive margin created after the breakup of the South American and African continental plates during Late Jurassic – Early Cretaceous, followed by rifting and drifting of the South Atlantic Ocean, creating huge accommodation space for marine anoxic shales and marine clastic successions over various cycles. Several petroleum systems have been proven in this basin previously. The A-J-1 well (1981) targeted the synrift graben near the coast, and found the only oil prior to 2022, a coast-aligned rift with 10m oil pay near the base of the syncline. In the 1970s Chevron discovered gas (Barremian) at the Kudu field in Namibia, sadly still undeveloped to this day. Soekor found small gas fields at A-F1 and A-E1 in Block 1, against the maritime border, and a larger field to the south at Ibhubesi in a 1986/87 campaign, but again currently not commercialised.

In a basin where petroleum explorers were divided on prospectivity, the results in February 2022 have spectacularly blown holes in most theories. Whilst some observers feared a lack of oil-prone source rock south of the Walvis Ridge, where the Cenomanian and Turonian was either not deposited or too shallow (both cases proven in some of the 24 wildcats drilled to date offshore Namibia), others could not successfully model the Lower Cretaceous anoxic Kudu Shale to hit the sweet spot of burial history (for good source and charge conditions) coinciding with good quality sand deposition. The results of Shell’s drilling campaign at Graff, in 1,900m of water, define a classic Upper Cretaceous passive margin slope sand system charged directly from the Aptian Kudu Shale, with amplitude support. Venus-1X, drilled in 2,900m of water, is less conventional, and took a great deal of modelling and finessing to map a low relief deep marine basin floor fan sitting on a similar Aptian source rock. Both plays have worked in the last few months, catapulting Namibia, and in time perhaps South Africa, into the super league of global prolific oil basins. Venus especially is a step beyond the ordinary, with a large, distal fan creating a huge target; a play that will reverberate for years around many passive margin abyssal basins.

There are many more opportunities to test in this enormous Cretaceous delta. The Upper Cretaceous source may yet be found to be mature in some areas, while the deepwater basin floor fan model is often repeated from here to South Africa. The ‘Kudu’ shale is seen to persist as far north as the Walvis Ridge, where basin modelling strongly suggests a burial history resulting in a mature source rock. Recent events have shown that several wells are required to find the sweet spots, and south of the Walvis Ridge several wells have come close, with oil recovered at Wingat and good source rock results in the Aptian at Murombe, while well 2012/13-1 revealed trace live-oil in the Maastrichtian.

With energy costs surging across the world, and the appetite for rapid large-scale deepwater developments strengthening, the future is bright for the Orange Basin.