I fell in love with fossils like many others, as a child, hunting on the world-famous Jurassic Coast in Dorset in the UK, a UNESCO World Heritage site, and location of many SSSIs (Sites of Special Scientific Interest). I will never forget a family holiday where my father Paul helped me rescue a small but well-preserved ichthyosaur vertebra as the tide came rushing in one day on the beach at Charmouth in Dorset. I have been collecting ever since (Figure 1).

Fossils are ingrained in our culture and folklore – did you know that the Jurassic ammonite genus Hildoceras is named after St Hilda, who was thought to have turned a plague of snakes around Whitby (UK) to stone and sent them flying over the edge of the local cliffs? Dactylioceras (Figure 3), Hildoceras and Eleganticeras ammonites are so common along this stretch of the Yorkshire coastline, it is hard to walk along the beach and not find them. As recently as the early 1900s this superstitious view of the origin of these so-called ‘snakestones’ was still held by some townsfolk!

While we now have a much better understanding of the origin of fossils such as ammonites, belemnites and echinoids, to this day, fossils continue to challenge the way we think about the past and there may be some lessons we can learn from them, especially around the sensitivity of groups of animals and plants and the ecosystems that depend on them in response to changing environments. In some ways, turning Lyell’s famous maxim on its head, the past may be the key to the present!

Nearly everyone will have heard the theory that the extinction of the (non-avian) dinosaurs occurred at the Cretaceous to Tertiary (K–T) boundary because of the Chicxulub asteroid impact on the Yucatan Peninsula. Approximately 75 percent of the known flora and fauna on Earth became extinct around this time because of the resulting change in climate (likely also influenced by other factors such as the Deccan Traps volcanism). The older Permian mass extinction 252 million years ago is thought to have led to the eradication of as much as 96 percent of all known marine life because of environmental change resulting from the outpouring of the Siberian Traps, which was the biggest volcanic eruption in the history of the planet. This disaster lasted for hundreds of thousands of years and there are numerous other examples throughout the Phanerozoic where major faunal turnover has occurred.

In the present, global awareness of the impact of climate change has never been greater, and I write this as the critical COP26 meeting is in full force. But over geological timescales, Earth’s climate has been in a constant state of flux, long before the arrival of hominids. This change has driven natural selection, species evolution, and incredible diversity in the fossil record which makes the sciences of palaeontology and biostratigraphy essential tools for the geoscientist.

Utility in Geological Interpretation

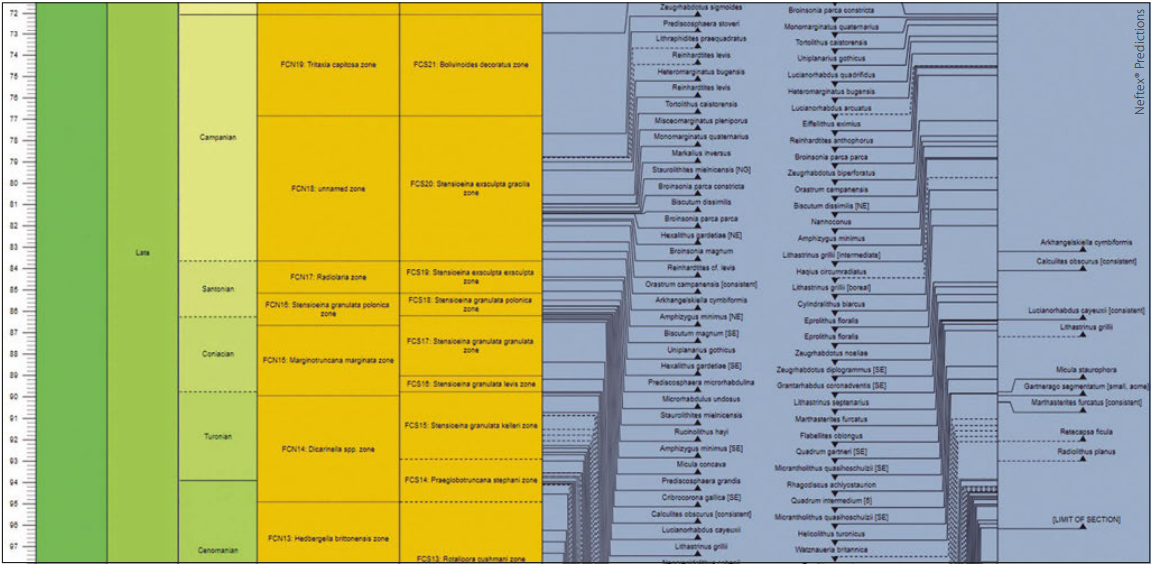

Fossils are the fundamental basis for defining the ages of sedimentary rocks. We can use diagnostic species (preferably those with short stratigraphic ranges) to define bioevents, biozones, assemblages and first and last appearance data to facilitate stratigraphic correlation (Figure 5). Some fossils provide important proxies for determining past palaeoenvironmental conditions (e.g., climatic zones from floral assemblages, air temperature from leaf stomatal indices and seawater temperature, salinity, chemistry and bathymetry from a range of different organisms based on occurrence, morphology, or measurements of the chemical compositions of their shells).

The degree of endemism and radiation of species can even help contest or validate conflicting geodynamic models. Did you know that the observed occurrence of radiolaria in the Barbados accretionary prism is important to debating the competing plate tectonic models for the Caribbean, or even that cosmopolitan frog radiation is useful for reconstructing the timing of the India break-up from Pangaea (Gondwana) assembly, and the evolution of the Palaeotethys and Neotethys Oceans?!

Some groups of fossils have broader utility and scientific value than others – the identification of diagnostic zone fossils, particularly in microfossil groups such as foraminifera, calcareous nannofossils, dinoflagellate cysts and other palynomorphs, are particularly well suited for borehole analysis and are an important instrument in the hydrocarbon industry.

However, there are many challenges with the several hundreds of thousands of taxa now described in the scientific literature. Taxonomically identical specimens have been described more than once (leading to many synonyms), original type-specimens were not described at a level to be truly diagnostic (nomen nudum) and some have since been destroyed or lost (a number of early type-specimens did not survive the air raids of World War II for example). Many fossils have also been arbitrarily assigned to taxa that have lost any real taxonomic value (so-called ‘wastebasket taxa’) – this is particularly problematic for some Jurassic marine reptiles and fossil fish.

Commercial World

Many key fossil groups are best represented in macrofossil specimens, such as ammonites which are revered as much for their beauty as for their stratigraphic value. Trade in fossils is big business, ranging from cottage industry in local fossil shops (typically close to the collecting localities), to large international enterprises. Do you have a slab of fossil fish on your wall? Chances are it probably comes from the Eocene Green River Formation in the United States. If you have purchased a trilobite, spinosaur tooth or mosasaur jaw in a fossil shop in recent years, they probably originated in Morocco. The fossil trade in Morocco alone is thought to be worth US$40 million a year and provides employment to more than 50,000 people.

Globally it’s a multi-billion-dollar industry, but fraught with complexity on legal rights, with some very high-profile cases where illegal trade has been halted by government intervention (most notably over the last decade for dinosaur eggs and other scientifically important dinosaur specimens from Mongolia and China). In Mongolia, for example, fossils are regarded as cultural items and have been protected by law from export since 1924. Even before this time, the commercial auction of a dinosaur egg collected on one of the Roy Chapman Andrews expeditions raised consternation from the thenruling Chinese government which invoked a year-long delay to the next planned expedition of the American Museum of Natural History. At the time, Andrews’ expeditions were ground-breaking in the discovery of clutches of dinosaur eggs at the Flaming Cliffs which were associated with Protoceratops dinosaur remains at the site. Exceptional specimens are now known today from elsewhere in the Gobi Desert, which include embryos, allowing species level identification to the ornithischian dinosaur Oviraptor philoceratops.

The stunning aragonitic Bearpaw ammonites are just one example of fossils from several sites in Canada where exceptional preservation has led to the discovery of important specimens. The Cambrian Burgess Shale in the Canadian Rockies is another, with many weird and wonderful early marine life forms including Hallucigenia, or the Lagerstätte of the Mistaken Point Formation in Newfoundland which preserves some of the best Ediacara fauna from the Precambrian. The latter are named after the Ediacaran Hills in Australia, another exceptional location which shows the proliferation of soft-bodied marine life prior to the Cambrian Explosion which led to the evolution of many of the most successful phyla which comprise modern life today. Ediacara fossils can even be found in the U.K., where Charnia masoni has been known since the 1950s, named after Charnwood Forest in Leicestershire where it was first discovered.

Returning to the Jurassic Coast, exceptional fossils continue to be recovered, long after Mary Anning set the bar for remarkable finds here. One such example was the recent discovery of a new species of ichthyosaur by Chris Moore, the subject of an excellent BBC documentary – ‘Attenborough and the Sea Dragon’. The specimen preserves fossilised skin which has been analysed using modern technologies like electron microscopy to examine the melanosomes, which provide information on the skin pigmentation, suggesting countershading on ichthyosaurs, as observed in modern sharks. Moving further to the east (and up into the Middle Jurassic), in Kimmeridge Bay, Steve Etches MBE has donated his world-class collection of Kimmeridgian material to establish the Museum of Jurassic Marine Life which includes some very important discoveries, not least fossil ammonite eggs!

Community

The vast amount of information now available about fossils on the web, through online museum collections, dedicated websites, research papers, and social media continues to significantly improve the accessibility of fossil collecting, palaeontological and biostratigraphic sciences to all. Even a casual look will reveal literally millions of specimen images! There is a thriving and strong community of contributors, private collectors and outstanding preparators that share how and where to find amazing fossils, how to prepare them, and how to build a safe and effective preparation space to make it all happen. Modern preparation standards are now so advanced that museum-grade specimens are becoming the norm, even in private collections.