Distances in Namibia are large, and many roads are gravel, so the most convenient way to tour is in a 4×4 camper (Figure 1). Our Namibian adventure began at the Windhoek airport, where we collected our fully equipped camper and were rolling down the highway enjoying the expansive vistas within an hour of our arrival.

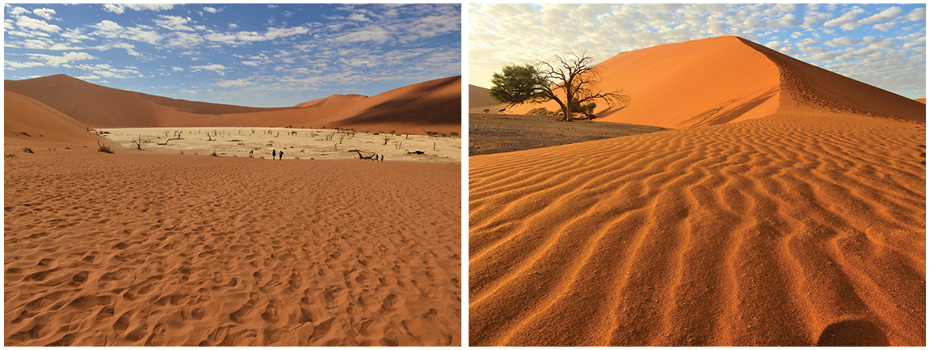

Namibia is famous for the hyper-arid Namib coastal desert. Three factors conspire to create this hyper-aridity. The first is the country’s 17–29°S latitude; many of Earth’s great deserts lie within this belt, and because air on the sinking limb of the Hadley Cell atmospheric circulation is loathe to release its water vapour as rain. The second is that prevailing winds blow from the south-east, leaving Namibia’s west coast in the rain shadow of the inland plateau. Lastly, the coastal Benguela ocean current delivers cold water from the Antarctic that cools the coastal air, reducing its capacity to hold water vapour. This same combination of factors has controlled Namibia’s climate ever since Gondwana broke apart almost 130 Ma, making the Namib the world’s oldest desert.

In addition to the break-up of Gondwana and its accompanying flood basalts, Namibia’s beautifully exposed rocks highlight three additional marquee events: the Neoproterozoic ‘Snowball Earth’ episodes that occurred between 720–635 Ma, the Damara Orogeny, a mountain-building event that completed assembly of the Gondwana supercontinent between 560–550 Ma, and deposition of the Karoo Supergroup, a series of Late Carboniferous through Jurassic sediments that accumulated in basins that formed behind the rising mountains of South Africa’s Cape Fold Belt.

Self-drive Safari: Etosha National Park

A must-see destination on any Namibian itinerary is the magnificent Etosha National Park. The park’s east gate lies 500 km north of Windhoek on a sealed road. Tsumeb, the park’s gateway town, is world famous among mineral collectors for exotic, gem-quality mineral specimens. Between 1905–1996, the Tsumeb copper-lead-zinc mine extracted 30 million tonnes of highgrade ore from an unusual pipe produced by karst collapse during the Damara Orogeny of the Neoproterozoic Otavi Limestone. The mine is the type locality for 56 different mineral species; many of its germanium minerals are found nowhere else.

Etosha is our favourite game park for two reasons. First, the sparse vegetation makes animal spotting comparatively simple. Second, Etosha can be seen on a self-drive safari; we chose how long to linger at each stop instead of being locked into a group timetable. The park surrounds the 120-km-long Etosha salt pan. Although the pan itself is desolate, springs to the south deliver groundwater to a series of waterholes that sustain scrubby vegetation and a diverse fauna that includes elephants, giraffes, rhinoceros, leopards, and lions.

Extraordinary Rocks and Ancient Peoples: Twyfelfontein

Namibia’s Otavi Group, which was integral to validating the Snowball Earth hypothesis, displays outstanding exposures of glacial diamictite directly overlain by thick marine ‘cap carbonates’. These record the dramatic climatic fluctuations Earth experienced between about 720–630 Ma, when the climate cycled from the ‘icehouse’ Sturtian glacial episode to a sweltering ocean in a ‘hothouse’ world, then back to an icehouse during the Marinoan glaciation, and finally back to a hothouse. We spent a delightful couple of hours surveying excellent diamictite and carbonate exposures riddled with 2-cm-diameter paleomagnetic sample holes in a small gorge traversed by a paved highway immediately north of Fransfontein, a 250 km drive from Etosha’s south gate.

Our next destination was Twyfelfontein, which was designated a World Heritage Site because of its 5,000 petroglyphs carved by ancestors of today’s San people (often called Bushmen) on desert-varnished red sandstone. The petroglyphs were outstanding, and we were equally captivated by this area’s abundant lava-capped mesas underlain by red rock, which reminded us of Utah’s famed Canyonlands, minus the crowds.

On the 120-km drive west from Fransfontein to Twyfelfontein, we traversed rocks representing all the major stages of Namibia’s geologic history. We started in Neoproterozoic Snowball Earth rocks, which were deformed during the Damaran Orogeny. Farther west, isolated granite koppies (bedrock hills) rose above the desert floor (Figure 2). The koppies consist of post-tectonic Cambrian granite that intruded as the Damaran Orogeny waned. Further west rose mesas consisting of Late Carboniferous and Permian Karoo Supergroup sediments capped by resistant basalt or rhyolite flows erupted 133–132 Ma from the Etendeka hotspot. Burnt Mountain, ten kilometres south-east of Twyfelfontein, is a prime example; its pastel slopes of Permian lake mudstone are capped by an Etendeka basalt flow. Nearby attractions include the Petrified Forest, which displays petrified logs washed by floods down a Permian river, and the Organ Pipes, consisting of columnar Etendeka diabase (Figure 3).

Desert Fogs: The Skeleton Coast

Our next stop was Namibia’s famed Skeleton Coast. Heading west, the already sparse vegetation dwindled to nearly zero as we descended from the plateau and entered the coastal rain shadow. We were startled to see a lone oryx ambling across the barren gravel plain we were traversing. Shallow groundwater beneath ephemeral drainages does support vegetation, thus explaining how life thrives in this moonscape; travellers are advised to avoid these washes lest they become dinner for a desert lion.

Occasionally, we spotted an odd-looking plant with a metre-wide tangle of broad, leathery leaves sprawled across the otherwise barren plain. This extraordinary plant, Welwitschia mirabilis, is one of Earth’s oldest living creatures; individual plants are as old as 1,500 years (Figure 5). The species, which grows only in the Namib Desert, is a living fossil, the only living representative of its ancient genus.

When we reached the coast, we registered for our mandatory day-trip permit to traverse the Skeleton Coast National Park. We then passed through a metal gate adorned with skull and crossbones and started down a long, straight road ploughed across the salt flats, stopping occasionally to explore one of the many shipwrecks that dot the coast (Figure 6). The omnipresent fog reduces the contrast between land, sea, and sky, adding yet another dimension to the surreal sensation of traversing this empty landscape.

After traversing 219 km of empty coastline, we encountered the first major road junction since passing through the skull-and-crossbones gate. This inland road leads 100 km to the Brandberg, Namibia’s highest mountain at 2,573m. This massive granite stock was emplaced 130 Ma, during the Etendeka large igneous event. It has been exhumed from a 5-km depth, with most erosion occurring between 80–60 Ma. Because the granite resisted that erosion better than the surrounding rocks, today it towers 1,800m above the surrounding coastal plain. The Tsisab Ravine on Brandberg’s west flank has been sacred to the San for millennia; more than 45,000 painted pictographs have been found throughout the ravine’s complex topography. The most famous is the so-called ‘White Lady’, which can be visited on a 1-hour guided hike.

The Spitzkoppe, which lies just north of the main highway connecting Windhoek to the scenic coastal cities of Swakopmund and Walvis Bay, is another exhumed Cretaceous pluton (Figure 7). Although less massive than the Brandberg, it is even more spectacular, hence its ‘Matterhorn of Namibia’ nickname. Its sheer, 600m high granite walls are a premier rock-climbing destination.

Guardians of the Coast: Sossusvlei Sand Dunes

The coast south of Swakopmund and Walvis Bay is every bit as arid as the Skeleton Coast, but its character is dramatically different. Abundant sand has drifted into huge dunes not found farther north. Dune 7, a short 13 km drive from Walvis Bay, is purported to be the tallest sand dune on Earth. Tourists flock to climb its impressive 383-metre face.

The final stop on our Namibian 4×4 adventure was nearby Sesriem Canyon. It combines gorgeous desert scenery with typical Namibian geologic and geomorphic diversity, making it a fitting finale. Here the (usually dry) Tsauchab River plunges off a resistant rim of Miocene conglomerate, carving a 30m deep canyon into the softer sandstone below. The coastal dunes to the west glowed red in the evening light, which also illuminated the dramatic Great Escarpment to the east. This view encapsulated for us Namibia’s stark beauty and extraordinary geoheritage. We saw countless amazing sights in our travels, but we barely scratched the surface of what Namibia offers.