Most tourists coming to New Zealand land in Auckland and, at most, stay overnight before moving on to see the geothermal and volcanic highlights of Rotorua, in the middle of the North Island, or flying on to the glacial landscape attractions of the Southern Alps and fjords in the South Island. If you can spare a few more days, you will be rewarded by the amazing and diverse geoheritage features in and around New Zealand’s largest city.

Auckland: City of Volcanoes

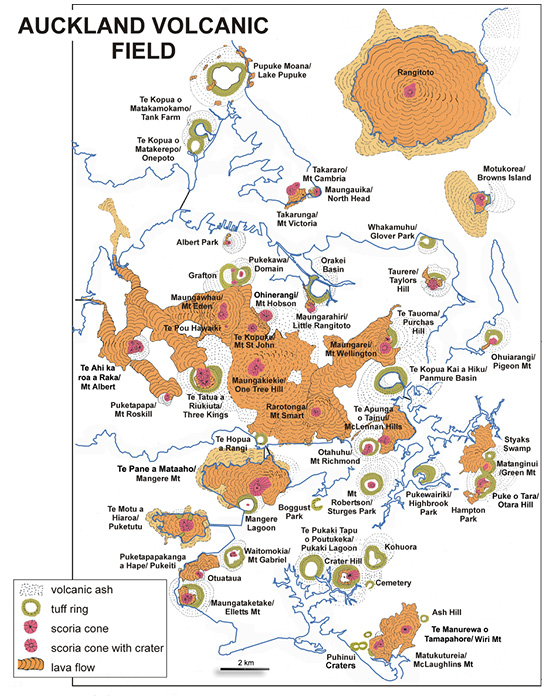

Auckland is one of those rare large cities that has been built over a dormant field of small, monogenetic basalt volcanoes. Fifty-three of them have each erupted just the once in the last 190,000 years. Far more of them erupted in the past 40,000 years than prior to that. As a result, their landforms are still crisp and uneroded, except that in many places the city’s suburbs have spread right over the lava flow fields and a number of the scoria cones have been removed or desecrated by quarrying activities that helped build the young city. The nineteen best remaining scoria/cinder cones and eight best maar craters are now major scenic oases and recreational reserves within the city.

Before the arrival of European colonisers in 1840, the Auckland Volcanic Field was greatly prized by the country’s first human settlers, the Maori. They grew crops in the rich volcanic soils, collected and caught shellfish and fish in the two major harbours and when skirmishes broke out between the various tribes, they used the cones as natural defensive positions. The summit and upper slopes of all the cones, large or small, were fortified at one time or other with the construction of defensive terraces, ditches and banks surmounted by wooden stockades. Today the earthwork remains of these forts, called paa, are highly valued archaeological and cultural heritage sites.

The youngest and by far the largest of Auckland’s volcanoes is Rangitoto, which erupted in the middle of the main Waitemata Harbour channel just 650 years ago. It is still intact and largely in its natural state and can be visited by tourists by taking a twenty-minute ferry ride from downtown Auckland. Most of the island is a gently-sloping shield of overlapping basalt flows. The summit consists of three abutting scoria cones, the highest and youngest of which has a deep bowl-shaped crater. The one-hour walking track to Rangitoto’s 259m-high summit passes over the rugged surface of many lava flows before the last steeper climb up the scoria cone, revealing panoramic views of the region. Ascending the track, the classic successional sequence of plants colonising the bare lava flow surfaces is clearly seen from lichens through mosses to vascular plants and kidney ferns.

For something a little different take a bus or drive over the harbour bridge to Takapuna Beach on the North Shore. The rocky reef at the north end, beside the carpark, is one of the best examples anywhere of a forest that has been fossilised as basalt moulds by a passing lava flow. Here you will see the 1m-high moulds of several hundred tree stumps in situ, where the passing molten lava has chilled and solidified around the lower trunks before mostly draining away and leaving the stump moulds standing proud. The lava flow was erupted from the field’s oldest volcano, Pupuke, about 190,000 years ago, and the basalt fossil forest buried and preserved beneath many metres of volcanic ash. Only in the Holocene, with the return of high sea level, has this ash been removed by intertidal erosion to display the fossil forest crisp and fresh. In addition to the moulds on the reef, walk along the coastal path to the north and you will see many horizontal moulds of branches that were rafted along and later incinerated by lava flows, but not before their shape had been captured in the cooling basalt.

If you are worried about an eruption while you are in Auckland, sleep soundly in the knowledge that there is a network of seismometers all focused beneath the city to detect the earliest signs of moving magma at depth. There is no shallow magma chamber. Instead, the magma rises to the surface in small batches from the partly molten asthenosphere, 60–90 km down. The first seismic signals are expected when the magma enters the base of the crust at 30 km depth and will give an estimated two days to two weeks warning of the next eruption; plenty of time for everyone to evacuate a 10 km-diameter area around the determined vent area.

Eroding Submarine Stratovolcano

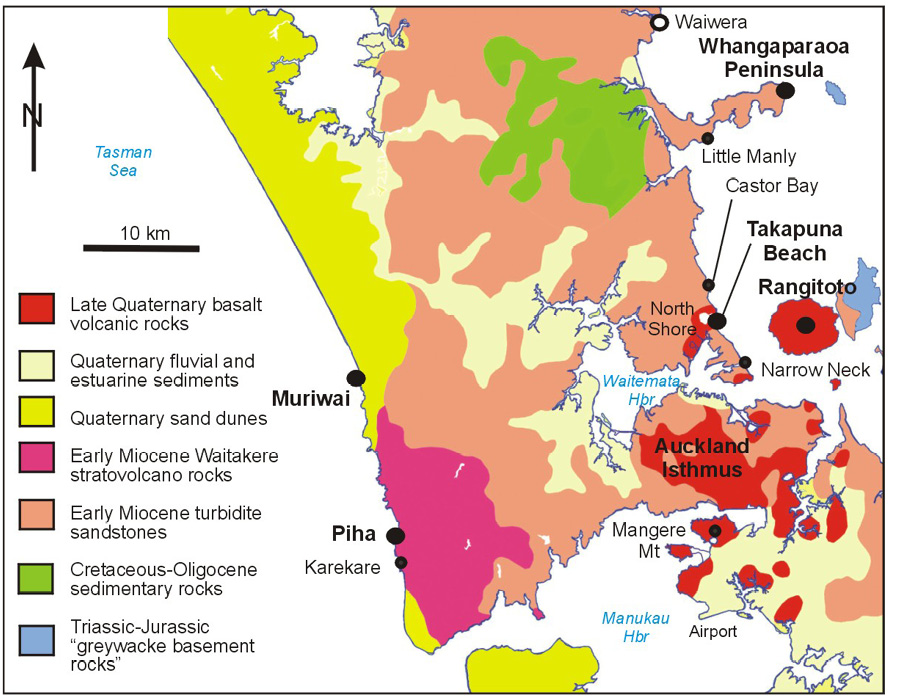

Auckland volcanoes are one of four similar Pleistocene–Holocene intraplate basalt fields that have erupted 150–200 km west of the modern volcanic arc that erupts above the subducting boundary between the Pacific and Australian plates. Twenty million years ago in the Early Miocene, the plate boundary and associated volcanic arc was further west and the southernmost volcano on the western arm of the Pacific Rim of fire at that time lay just to the west of present-day Auckland. The uplifted, eroded eastern remnants of this largely submarine stratovolcano now form the Waitakere Ranges, the city’s forested western skyline.

There are effectively four, no-exit roads out to the surf-battered, rocky Tasman Sea coast of the Waitakere Ranges. I recommend you try two of them. The one over the top to Piha and Karekare beaches takes you to the ancestral home of surfing in New Zealand at South Piha. One of New Zealand’s best-known views is from a lookout on the side of the road as you drive down the hill to the beach. The view up the rugged coastline stretches north beyond the imposing Whakaari/Lion Rock, the eroded neck of an ancient eruption centre standing tall in the middle of Piha Beach.

Walk around the shoreline or take the track over the cliff tops to the scenic Puaotetai Bay/The Gap, south of South Piha. It is surrounded by towering cliffs of stratified volcanic conglomerate that was left behind as lag deposits by debris flows that swept down the submarine slopes of New Zealand’s largest stratovolcano nearly 20 million years ago. Today the eroded stump of this long-extinct Waitakere Volcano spans 60 by 40 km with three quarters of it submerged offshore. In picturesque Puaotetai Bay there are classic examples of sea caves, tunnels, and a blowhole, all of which have been eroded along vertical joints or andesite dikes by the crashing waves.

The black sand grains at the top of these west coast beaches are titanomagnetite. They were a minor component in the huge Quaternary ignimbritic eruptions in the centre of the North Island, and have been transported here down the Waikato River and up the coast by longshore drift. They have been left behind in high concentrations around high tide level because of their high density, with more voluminous and much lighter quartz, feldspar and pumice being swept further north along the coast. Older Pleistocene sand dune deposits of titanomagnetite, 40 km to the south, provide the major feedstock to New Zealand’s only steel mill at Waiuku.

Giant Andesite Fans

Venture out to the west coast at Muriwai at the northern end of the Waitakere Ranges and you will join the throngs viewing New Zealand’s most accessible mainland gannet colony. Just to the south of this, however, in the cliffs above Maukatia/Maori Bay is one of the country’s most treasured geoheritage features – the spectacular columnar fans and pillows of a basaltic andesite flow that was erupted in 1,000–2,000m of water on the lower slopes of the Waitakere Volcano about 17 million years ago. Sea erosion of the cliffs has sliced a section right through a 400m-wide, 30m-thick pillow lava flow, exposing the large, solidified internal feeder pipes surrounded by more usual, 1–2m-diameter branching pillow lobes or fingers. From the beach look up and admire the flow and its huge fans of columns in the cliffs behind. On a good low tide, it is possible to walk south and see further smaller pillow lava flows up close and even dikes captured in time with an extruded pillow roll being squeezed out into the unconsolidated sediments just below the sea floor.

Highly Deformed Miocene Turbidites

The young volcanic rocks that underlie Auckland City are just a thin mantle that buries a rolling landscape of ridges and valleys eroded out of the region’s most common rocks, interbedded Early Miocene sandstone and mudstone. The sandstone layers were deposited by turbidity currents flowing down submarine canyons from the north into a rapidly subsiding deep bathyal-abyssal marine basin. The thinner and less erosion-resistant mudstone layers were deposited by the settling out of the fine tails of the turbidites and by slow hemipelagic mud sedimentation in between turbidity current events. This Waitemata Basin was formed as a result of the initial propagation of the modern Australian–Pacific plate boundary, obliquely beneath northern New Zealand.

The relatively soft Waitemata Sandstone strata can be seen forming 20–100m-high sea cliffs around the coastlines of most of Auckland’s two harbours, the Manukau and Waitemata. The total thickness of accumulated turbidites is about 1000m and these have been uplifted, tilted west and partly eroded down during several episodes of enhanced tectonism since sedimentation ceased, 17–18 million years ago. In many of the cliffs of the North Shore’s eastern beaches and particularly around the finger-like Whangaparaoa Peninsula, the strata exhibit sections of intense faulting and folding. The larger faults are probably of young age but it is clear that most of the mix of ductile and brittle deformation occurred within the upper parts of the sediment pile as it was accumulating.

One hypothesis is that there was a major seafloor failure event on the basin’s northern slopes involving as much as several hundred square kilometres of seafloor to a depth of up to 500m or more. No doubt this failure was a compound event with slabs progressively sliding downslope and thrusting over the top of earlier slide blocks and compressing, folding and fracturing strata around and beneath their toe. Other unrelated slope failure slumps are also likely to be responsible for some of the deformed sections. The best places to examine some of this amazingly complex deformation are at low tide in the cliffs south of Narrow Neck, north of Castor Bay, at Waiwera Beach, and all-around the Whangaparaoa Peninsula. I recommend an exciting four-hour walk during low tide around the tip of Whangaparaoa Peninsula from Army Bay to Pink Beach, returning overland through the natural bird sanctuary of Shakespeare Regional Park.

Further Reading

- Hayward, B.W. 2019. Volcanoes of Auckland: A field guide. Auckland University Press, 335 pp.

- Hayward, B.W. 2017. Out of the Ocean into the Fire. History in the rocks, fossils and landforms of Auckland, Northland and Coromandel. Geoscience Society of New Zealand Miscellaneous Publication 146, 336 pp.