Intensely secretive, for more than half a century Gulbenkian personally controlled five per cent of Middle East oil production and shaped the firms we know as Shell and Total.

The Red Line Agreement

The original Red Line Agreement map. © Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Every map has its legend. The map attached to the Red Line Agreement of 31 July 1928 is no exception. This agreement saw the companies we know as BP, ExxonMobil, Total and Royal Dutch-Shell join forces in the Middle East. Instead of fighting each other for control of the region’s oil, they would collaborate in a joint venture: the Turkish Petroleum Company (TPC).

TPC had been established by the Anglo-Armenian Calouste Gulbenkian back in 1912. Two years later the British Foreign Office and the Grand Vizier in Istanbul had given their blessing: rival powers were to cooperate not only in the oil-rich Ottoman provinces of Mosul and Baghdad, but in the entire ‘Ottoman Empire in Asia’. For Gulbenkian, who held 5% of TPC, it was a promising start.

By 1928, however, the ‘Ottoman Empire in Asia’ was a distant memory. The Great War broke out just a few months after TPC secured its concession. Allied to Germany, in the wake of defeat the Ottoman Empire had collapsed, triggering a wave of genocidal violence which killed a million of Gulbenkian’s fellow Armenians. A patchwork of mandates and protectorates was developing into the new nation-states we know today as Iraq, Jordan and Saudi Arabia. When it came to defining the ‘Ottoman Empire in Asia’ as it had been in 1914, therefore, the oilmen meeting in Ostend in Belgium that day in 1928 were in something of a fix.

The Ottoman Empire 1874. © Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

According to Ralph Hewins’s 1957 biography, all was confusion until Calouste Gulbenkian intervened:

‘When the conference looked like foundering, he again produced one of his brainwaves. He called for a large map of the Middle East, took a thick red pencil and slowly drew a red line round the central area. “That was the Ottoman Empire which I knew in 1914,” he said. “And I ought to know. I was born in it, lived in it and served it. If anybody knows better, carry on…”’

Gulbenkian’s TPC partners inspected the map, and it was good. Hewins continues: ‘Gulbenkian had built a framework for Middle East oil development which lasted until 1948: another fantastic one-man feat, unsurpassed in international big business.’

In his lifetime Gulbenkian studiously avoided the press, to the extent that today those who recognise the name often confuse the secretive Calouste with his publicity-seeking son Nubar. Londoners in particular fondly recall Nubar’s chauffeur-driven taxicab. Many contemporaries and some historians have equated Gulbenkian’s secretiveness with duplicity, rather than modesty. It is common to find Gulbenkian referred to as ‘a shadowy Armenian manipulator’, a ‘detested’ figure whose influence, we are told, derived ‘from the liberal dispensation of bribes’.

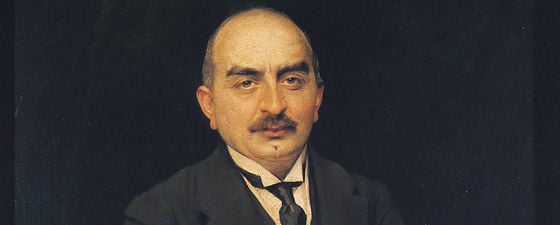

Calouste Gulbenkian – A Great Buccaneer of Oil

Calouste Gulbenkian, born March 1869, died 20th July 1955. © Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Others have been kinder. In his Pulitzer-winning history of the oil industry Daniel Yergin places Gulbenkian on a par with Rockefeller, Getty and Mattei, as ‘one of the great buccaneer-creators of oil’. But if Calouste Gulbenkian is known today, it is as the man who drew the red line. The 1928 Red Line Agreement embodied Gulbenkian’s personal claim to 5% of TPC’s oil, a claim which he later vested in a company, Partex, which continues to this day.

Yet on closer inspection the legend falls apart. Although the map was certainly left until the final phase of the negotiations that culminated at Ostend, Gulbenkian showed little interest in it. In fact, he was not even at Ostend on that fateful day. The others round this table were powerful empires and multinational companies, staffed by hundreds of employees, backed by armies of soldiers and sailors, as well as taxpayers and shareholders. They were hardly going to let Gulbenkian, an individual with no company or state behind him, scrawl red lines over their maps.

Gulbenkian had fought hard to get his quarrelsome British, French and American partners to agree to cohabitate in his ‘house’ (as he called TPC), and successfully defeated repeated attempts to defenestrate him. But he was not particularly bothered about the course of the red line itself. Nor was it his style to make pretty speeches. He worked as a back-room fixer, an intermediary between the worlds of business, diplomacy and high finance, a figure very different – and more interesting – than the Gulbenkian of legend. As Al Jazeera recently put it, Gulbenkian was ‘the world’s first oil fixer, broker and deal-maker’.

Gulbenkian at the age of 20. © Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

The spider at the centre of the emerging international oil and banking industry, Gulbenkian held empires and multinationals to ransom for more than fifty years. He would not have come to wield such power, however, had he not been an exceptionally skilled negotiator and financial architect. Oilmen from California to the Caucasus sought him out for his skill in raising capital on the stock markets of New York, London and Paris. He played an important, if previously unacknowledged, role helping both Royal Dutch-Shell and Total establish themselves as oil majors – notably as Svengali to Shell’s Henri Deterding.

Gulbenkian’s deals introduced American oil companies to the Middle East, and brought Royal Dutch-Shell to America – as well as to Mexico, Venezuela and Russia. The embryonic oil industry Gulbenkian found at the start of his career in 1900 was one dominated by a single oil producer and a single company: the United States and Standard Oil. At his death in 1955 the world oil industry was no longer an American monopoly, but an international cartel. Though the oil industry no longer resembles Antony Sampson’s “Seven Sisters”, the structure of multinational production, integration and partnerships remains the same. The web woven by Gulbenkian is with us still.

Creating the Turkish-Iraqi Border

In the 1920s the line which most exercised Gulbenkian was that separating Turkey from the new state of Iraq. Despite being ‘Turkish’, TPC’s relations with the Turks were poor. The British-mandatory regime in Iraq was more likely to confirm the company’s pre-war rights to Mosul’s oil. For TPC, therefore, it was crucial that Mosul’s oilfields ended up on the Iraqi side of any Turkish-Iraqi border. Unfortunately, the 1923 Lausanne Conference had failed to settle the border question, referring it to the League of Nations.

In June 1925 Gulbenkian proposed to get the League’s maps drawn so that the Mosul oilfields were on the ‘right’ (Iraqi) side of the border. He happened to know the cartographer assigned to the survey party, a fellow Armenian named Zatik Khanzadian and, as he explained in a letter to his TPC partners:

‘Khanzadian knows all the crooks [sic] and corners of the place, and as the other members [of the border commission] are not cartographers, it remains for him to make up the map according to certain instructions regarding topographical positions; I am given to understand that he can turn this as he likes, and so Khanzadian desires to get into personal and confidential touch with me, relying on my position and name to keep the whole thing [secret]. He is desirous of knowing which are the points that our company would like to remain on the side of Iraq.’

Why bother with conventions, protocols and treaties when international borders could be fixed your way, for just £2,000 (£100,000 in today’s values)? Others might go to the starting line. Gulbenkian went straight to the finish.

So, Who Was Calouste Gulbenkian?

Rembrandt’s ‘Pallas Athena’ was sold to Gulbenkian by Stalin. It is now owned by the Gulbenkian Foundation. © Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Born in Constantinople in 1869, Gulbenkian came of age in the Ottoman Empire, only to see this familiar world tear itself apart. He was not the only Ottoman Armenian to find refuge in the West, but he was the only one to make it big in this unfamiliar world. Far from holding him back, the destruction of his homeland and a loner personality became keys to his success: as a secretive man without loyalties to any one empire, state or company, Gulbenkian could present himself as the ultimate honest broker.

For ‘westerners’ he was a trusted source of intelligence on the Middle East. For ‘easterners’ he was someone to turn to in order to find out what the Great Powers and their mighty oil companies were up to. This was as true of Sultan Abdülhamid II in 1900 as it was of the Shah of Iran and Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia four decades later. Gulbenkian was a diplomat in the service of both the Ottoman and Persian empires. Even Stalin sought Gulbenkian’s advice, rewarding him with Rembrandts from the famous Hermitage Museum. No other business figure in the history of the oil industry wielded such influence, over such a scale, for so long.

Gulbenkian’s story is timely. Whether we look back to the First World War and secret agreements like Sykes-Picot a century ago, or whether we consider the ongoing struggle for control of Iraq or current debates about capitalism, politics and identity, Gulbenkian is hiding in plain sight, challenging us to pin down the source of his fabulous wealth and influence. How did a man who knew nothing of geology and who never visited Iraq, Saudi Arabia or any of the Gulf states lay claim to 5% of Middle East oil production? Once he secured this stake, how did he manage to hold on to it, and so become the richest man on earth? How did a shy recluse bridge divides of East and West which seem insurmountable today?

The roof terrace of Gulbenkian’s Paris palace. © Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Gulbenkian built a fabulous palace in Paris which he filled with treasures, not only paintings from the Hermitage, but Greek coins, Egyptian antiquities, Persian carpets, Iznik faience and Japanese netsuke. Today his collections are housed in Lisbon, next to the headquarters of the foundation which bears his name and which remains one of the wealthiest foundations in the world. Yet the great collector himself never slept in his palace. He lived in hotels. He held four different passports and intended his foundation to be equally international in ambition.

This freewheeling, cosmopolitan spirit reflected the pre-1914 world of unrestricted international exchange of capital, technology and people. Such globalisation subsequently went into retreat, until the 1980s. Now the tide is going out again: free enterprise and free movement are under assault from right and left. Trade disputes are trumped up. Sinister ‘citizens of nowhere’ are made up. And the cheers and the votes role in. Surely Gulbenkian, the ultimate ‘citizen of nowhere’, has something important to tell us at this moment in history.

Mr. Five Per Cent: The Many Lives of Calouste Gulbenkian

If you want to learn more about Calouste Gulbenkian, Jonathan’s new biography reveals the man behind the myths. Called Mr. Five Per Cent: The Many Lives of Calouste Gulbenkian, the book was published in January 2019 by Profile Books.

Further Reading on the History of Oil in the Middle East

Some recommended GEO ExPro reading relating to, or similar in content to, the history of oil and gas exploration in the Middle East.

Once Upon a Red Line – the Iraq Petroleum Company Story

Michael Quentin Morton

A consortium of four oil majors (today’s BP, Shell, Total and ExxonMobil) and oil magnate Calouste Gulbenkian, the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) was designed to explore and extract oil in the Middle East. Amid controversy about its role as the ‘Red Line Cartel’, its pioneering contribution to the oil development of the region is often overlooked.

This article appeared in GEO ExPro iPad App 6 – 2013

The Emergence of the Arabian Oil Industry

Rasoul Sorkhabi, Ph.D.

In terms of petroleum reserves and production, the Middle East is second to none. The stories behind the first discoveries in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in the 1930s are also intriguing.

This article appeared in Vol. 5, No. 6 – 2008