Oman is often described as a geologist’s paradise – with good reason. Boasting a huge diversity of rocks ranging in age from Late Proterozoic basement to Quaternary sands, well exposed in scenic vistas, and cut over millennia into wonderful landforms, there is always something fascinating to look at. From the jagged peaks of the Al Hajar Mountains and the deep inlets of the Musandam Peninsular to the wide Wahiba sand sea and the sabkhas of the Empty Quarter: there are thousands of geotourism stories in a single country. Its geological situation between the converging African and Asian land masses means that Oman has been subject to extremes of rock evolution, resulting in the assemblage of some of the most unique geological features to be found in the world, including the Earth’s largest mass of exposed ancient oceanic crust, the Samail Ophiolite.

Here we take a look at just one of the country’s many geological wonders: Wadi Nakhr, in the Al Hajar Mountains.

The Al Hajar Mountains of Oman

The Al Hajar stretch 700 km across the north of the country, majestically dominating the scenery as they rise abruptly to over 3,000m from the coastal plain. The sediments at the core of the range were mainly laid down during the Late Permian to Late Cretaceous in the Neotethys ocean basin that had resulted from the break-up of Gondwana. As the Arabian platform slowly submerged, almost 3,000m of predominantly shallow marine limestones, with occasional clastic pulses, were deposited. This formed the Hajar Supergroup, which provides many of the best reservoir and source rocks throughout the Arabian Peninsula , including in the supergiant Rumaila-West Qurna field.

As the subduction of the Arabian Plate below the Eurasian Plate continued and partial closure of the Tethys basin commenced, the carbonate sequence was uplifted and compressed, and oceanic crust was pushed from the north over the continental crust to form the ophiolite complex which makes up the majority of the Al Hajar range. The carbonate platform sediments were folded during these movements, resulting in the westward-dipping anticlinal structure of the Jebel al Akhdar structure, which is one of only a couple of places where the underlying carbonates outcrop in the mountains. The highest point of Jebel al Akhdar is Jebel Shams, which at 3,010m is also the highest mountain in Oman.

The flanks of Jebel Shams are cut by a number of deep valleys, known in Arabic as wadis, running perpendicular to the strike of the anticline. The deepest of these is the 12 km-long Wadi Nakhr, which cuts down through over 1,500m of sediment, thus providing one of the best exposures of these important Cretaceous reservoir horizons.

The road to Jebel Shams gives a snapshot of some of the varied geology that this fascinating country offers the geo-tourist – before the final corner is turned and a deep crevice in the earth drops down into the hazy depths of Wadi Nakhr.

Exotics and Supergroups

The road starts in the small town of Al Hamra, about 30 km north-west of the tourist centre of Nizwa, and a couple of hours drive from the capital, Muscat. The road runs alongside a wadi; for much of the year the river bed is dry, but the water table is high enough for there to be plenty of vegetation along the valley, helped by the highly effective ‘falaj’ system of irrigation found throughout Oman.

The valley is quite wide to begin with, with sides which rise steeply from 700m on the valley floor to over 1,600m. On the right (northern) side of the road are the gently-dipping layered limestones of the Hajar Supergroup, while on the southern side things look quite different. The road here closely follows the contact between the autochthonous Hajar Group rocks and the allochthonous rocks of the Hawasina complex, which comprise deep marine and continental slope sediments deposited in the ocean basin on the southern margin of the Neotethys ocean. During the Upper Cretaceous, the obduction of the Semail ophiolitic complex led to these deep sea Hawasina sediments being thrust over the Hajar Supergroup.

Towering over the valley a few kilometres away to the south is Jebel Kawr, 35 km long and at 2,960m nearly as high as Jebel Shams. This is an example of the ‘Oman exotics’ – so-called because their lithology cannot be matched laterally to any of the adjacent rocks. It is composed primarily of Late Triassic limestones overlain by Jurassic pelagic limestone and overlies Triassic volcanics. It is believed to have been formed in an ocean island tectonic setting before being thrust over the Hawasina complex and folded by the tectonic movements which created the Jebel al Akhdar dome. The thick carbonate unit contains shallow marine fossils such as corals, crinoids and stromatolites. The volcanics underlying the limestone can be clearly seen along the southern side of the road from Al Hamra, both as basalt and as a volcanic breccia.

About 10 km from Al Hamra is the village of Ghul, which lies at the southern entrance of Wadi Nakhr. As is common in Oman, there is a picturesque but abandoned and crumbling old village, which lies on one side of the wadi mouth, with the modern village surrounded by date palms and irrigated gardens on the opposite bank.

It is possible to trek up Wadi Nakhr from here; a strenuous hike, but one which exhibits the full sequence of the Hajar Group. At the entrance to the wadi there is the massive limestone of the Natih Formation, conformably overlying the shaley Nahr Umr Formation, which together form the Mid Cretaceous Wasia Group. They are underlain by limestones and marls of the Lower Cretaceous Kahmah Group. Moving northwards further along the wadi floor, the southerly dip of the rocks mean that the canyon has eroded down to expose the Jurassic Sahtan Group, with oolitic black limestone underlain by rust brown shaley units deposited in a shallow marine environment.

What is the Hajar Supergroup?

The road starts in the small town of Al Hamra, about 30 km north-west of the tourist centre of Nizwa, and a couple of hours drive from the capital, Muscat. The road runs alongside a wadi; for much of the year the river bed is dry, but the water table is high enough for there to be plenty of vegetation along the valley, helped by the highly effective ‘falaj’ system of irrigation found throughout Oman.

The valley is quite wide to begin with, with sides which rise steeply from 700m on the valley floor to over 1,600m. On the right (northern) side of the road are the gently-dipping layered limestones of the Hajar Supergroup, while on the southern side things look quite different. The road here closely follows the contact between the autochthonous Hajar Group rocks and the allochthonous rocks of the Hawasina complex, which comprise deep marine and continental slope sediments deposited in the ocean basin on the southern margin of the Neotethys ocean. During the Upper Cretaceous, the obduction of the Semail ophiolitic complex led to these deep sea Hawasina sediments being thrust over the Hajar Supergroup.

Towering over the valley a few kilometres away to the south is Jebel Kawr, 35 km long and at 2,960m nearly as high as Jebel Shams. This is an example of the ‘Oman exotics’ – so-called because their lithology cannot be matched laterally to any of the adjacent rocks. It is composed primarily of Late Triassic limestones overlain by Jurassic pelagic limestone and overlies Triassic volcanics. It is believed to have been formed in an ocean island tectonic setting before being thrust over the Hawasina complex and folded by the tectonic movements which created the Jebel al Akhdar dome. The thick carbonate unit contains shallow marine fossils such as corals, crinoids and stromatolites. The volcanics underlying the limestone can be clearly seen along the southern side of the road from Al Hamra, both as basalt and as a volcanic breccia.

About 10 km from Al Hamra is the village of Ghul, which lies at the southern entrance of Wadi Nakhr. As is common in Oman, there is a picturesque but abandoned and crumbling old village, which lies on one side of the wadi mouth, with the modern village surrounded by date palms and irrigated gardens on the opposite bank.

It is possible to trek up Wadi Nakhr from here; a strenuous hike, but one which exhibits the full sequence of the Hajar Group. At the entrance to the wadi there is the massive limestone of the Natih Formation, conformably overlying the shaley Nahr Umr Formation, which together form the Mid Cretaceous Wasia Group. They are underlain by limestones and marls of the Lower Cretaceous Kahmah Group. Moving northwards further along the wadi floor, the southerly dip of the rocks mean that the canyon has eroded down to expose the Jurassic Sahtan Group, with oolitic black limestone underlain by rust brown shaley units deposited in a shallow marine environment.

Spectacular Views

Beyond Ghul the road begins to climb more steadily and the valley sides become even steeper. It runs along another geological contact, this time between the Natih Formation and the overlying syntectonic Cretaceous Muti Formation. This is a complex mix of sediments with conglomerates, mega breccias and irregularly sorted deposits including yellow siltstones with a chaotic structure, often with large blocks of the Natih Formation embedded within the conglomerate. It records the transition from a passive margin to a foreland basin during subduction.

About 16 km from Ghul, after a steep and winding climb, the road begins to flatten out at a height of about 1,500m and runs across a polished limestone pavement for several kilometres. This is the top of the Natih Formation, marking the cessation of marine deposition. A few kilometres further, and there is a spectacular viewpoint. In the distance is the sharp outline of Jebel Misht, the most spectacular of the Oman ‘exotics’, its dramatic white limestone cliffs rising 1,000m above the surrounding hills.

By this stage the road is no longer paved, and a 4×4 is required to continue – but it is well worth the effort. At the most northerly point of the drive, the track climbs along the edge of the steep white cliffs of another limestone exotic, with volcanics outcropping underneath. Vegetation is sparse at this height, so the long-haired goats, for which the area is famed, can be seen climbing trees in their search for food. The road now closely follows the unconformable contact between the Natih and the overlying, sometimes tightly folded shales of the Muti Formation.

The track levels out at a height of about 2,000m and heads southwards across the limestone plateau for a few kilometres – and a yawning chasm begins to be revealed. Finally, 40 km and a couple of hours since leaving the village of Ghul – now only 6 km south as the crow flies – there is the most spectacular viewpoint: the Grand Canyon of Oman.

The Balcony Walk at Jebel Shams

In the far distance to the right is the Jebel Misht limestone ‘exotic’, probably originally an ocean atoll. On the left in the distance is Jebel Kawr, also an exotic, whilst the high cliff in front of that is Jebel Misfa. The Hawasina deep oceanic sediments of the Hamrat Duru Group form the intervening dark low hills, with the top Natih Formation limestone pavement in the foreground. Photo credit: Jane Whaley.

The canyon is over a kilometre wide here, and to the north it can be seen cutting deeply into the flanks of Jebel Shams. At the viewpoint there is an almost sheer drop to the canyon floor over 1,000m below, where at the very bottom a few patches of greenery can be seen, following the stream bed through the wadi. The deep ravine of Wadi Nakhr probably formed during the uplift of the Jebel al Akhdar dome, enhanced by successive wadi floods, with some speculation that the collapse of underground caverns may have added to its development. The entire sequence of the Hajar Supergroup is exposed on the wadi sides, with the massive limestone beds forming near vertical cliffs, interspersed by weaker, shaley horizons. Although not as huge as the American Grand Canyon, it is still an awe-inspiring sight!

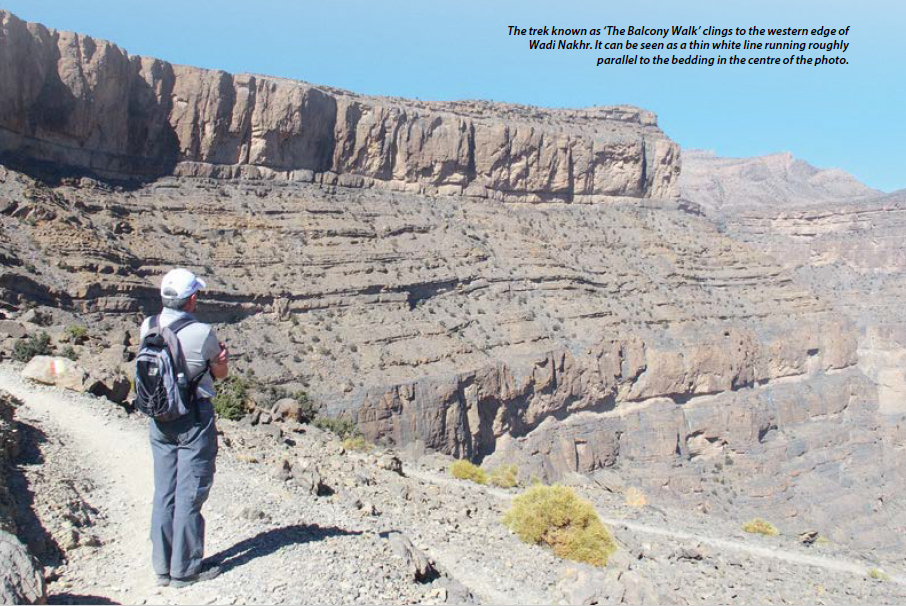

The journey is not yet over. A few kilometres further south, and the road finally ends in the windswept village of Al Khateem, sitting precariously on the edge of the canyon. Although the sides of the ravine look impenetrable, at this point it is possible to pick up a trail which travels inside the western rim of the canyon. Aptly known as ‘The Balcony Walk’, this old donkey path roughly follows the bedding, with occasional scrambles to a lower horizon. It affords tremendous views into the silence of the canyon, and of its geology – but with drops of hundreds of metres to one side in places, it is not for the faint-hearted.

Extreme as this environment seems, the Balcony Walk eventually reaches the ruins of a small village, As Sab, about a 2-hour trek from Al Khateem, which was inhabited until not long ago. It is perched on the cliff side with rough-hewn terraces clinging to the rock beside it – and a drop of 800m below. A spring at the base of the limestone wall above the village provided the water for the terraced gardens, and many of the houses are still standing as they are protected from the elements by overhanging rocks.Heading back up the trail, the lucky walker may catch a glimpse of the distinctive black and white Egyptian vulture hovering on the thermals rising up from the valley; or even, as we did, an intrepid paraglider, 1,000m above us, silently circling over the canyon. Surely, that paraglider had one of the best views in the world!