Kevin Topham has had an eventful life. Born in Retford, Nottinghamshire, in the English East Midlands, he joined the RAF when still in his teens to fight in WWII. His four brothers were also all in the services and miraculously all survived.

Kevin remained in the RAF until the early 1950s, working for much of that time as a bomb disposal expert. When I asked him what drew him to a line of work the thought of which terrifies most of us, he simply says, “I was 17; you think you’re invincible at that age. I was quite mechanically minded, and if the RAF decided you did something, you didn’t have much choice!”

First UKCS Discovery

On leaving the RAF Kevin joined Kirklington Hall, BP’s research station at Eakring in Nottinghamshire as a mechanical engineer. “I worked all over England and Scotland, drilling wells and finding oil and gas. I was even involved in drilling the first well at Wytch Farm, although it wasn’t successful that time,” Kevin says. “And we fracked all our wells! People seem to think fracking – or, as I prefer, hydraulic fracturing – is a modern process, but we’ve been doing it for years.”

By the 1960s oil companies had begun to look seriously at the UK North Sea, and BP was no exception. “All of us based out of Eakring were experienced drillers, so when the company decided to start exploring the southern North Sea, they transferred us onto the project.”

BP had converted a barge, the Sea Gem, for use as a drillship by welding on 10 steel legs and adding a helipad, living quarters, radio shack, drilling tower and associated structures. “I helped construct and test the derrick in Eakring before we transferred it to the Sea Gem,” Kevin explains. “The whole thing was quite hastily put together – there was a lot of pressure to get a British rig working in the North Sea. Three wells had been drilled by American rigs, the first in December 1964, but they’d all been dry.”

In May 1965 the Sea Gem was towed out of Middlesbrough docks. The crew, including Kevin, flew out by helicopter to join her and by early June they were drilling about 65 km east of the English coast. “We were guinea pigs,” he says. “Although some of the team had worked offshore Saudi, no one had experience of drilling in the North Sea. There was very little safety gear and no protective clothing. I travelled out with my RAF greatcoat to keep me warm.”

On 17th September there were signs of gas and the drilling fluid returning from the bottom of the well was frothing: the Sea Gem had made the first discovery of hydrocarbons in the UK sector of the North Sea – the West Sole field. “To be honest, there wasn’t that much excitement,” Kevin recalls. “After all, we were experienced drillers and we’d found oil and gas before – it was just normal work for us. We also didn’t know what they would do with gas, whether they would be able to pipe it to shore. And we knew that a show didn’t necessarily mean a major discovery – in fact that first evidence of gas at 2,500m wasn’t commercial.”

The team continued drilling to over 3,000m and in December 1965 BP and the UK government announced that testing had shown that there was sufficient gas in the field to justify building a pipeline to bring it ashore.

Disaster at Sea

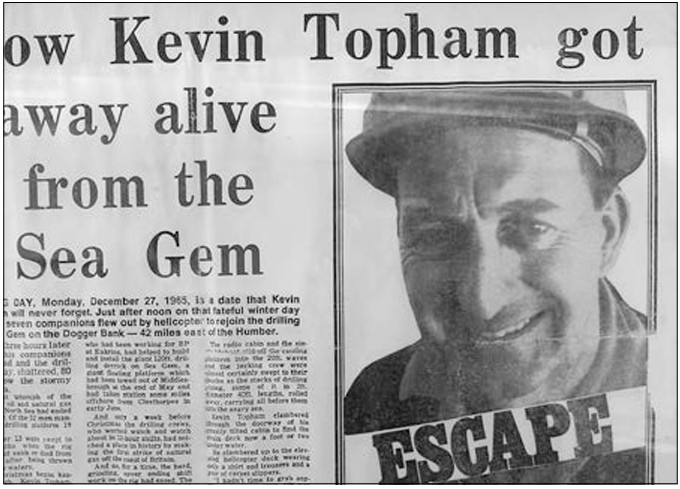

Having completed testing, the plan was to move the Sea Gem to a new drill site. Working a 10-day rota, Kevin expected to remain on board over Christmas 1965 – but a message came through on Christmas Eve saying that 12 personnel would be allowed home for Christmas, on standby for moving the rig when the weather permitted. Kevin continues the story.

“We talked among ourselves and those who wanted to have New Year off – mostly the Scots – stayed on board and the rest of us were delighted to be flown home to spend Christmas with our families. But on Boxing Day [26th December] there was a knock on the door and the BP driver told me I’d been recalled to move the rig and he’d pick me up early the next morning. Nine of us flew out to the rig on 27th December, looking a bit cheesed off at being recalled; four never returned.

“We arrived in time for an excellent late Christmas dinner, and then went to our cabins to change into working clothes. The rig was in the process of being ‘jacked down’ [when the hull is lowered down the legs until it is floating, before the legs are raised from the seafloor]. I wasn’t due on shift until we began the move later that night, so I sat on my bed and picked up a magazine. Suddenly, there was a sharp judder throughout the barge, and I felt like I was going down in a lift. The shelf came off the wall behind me and hit me on the head and as I made for the door there was a terrible lurch and the floor tilted to about 45°. Dashing outside, I realised that two of the legs had collapsed and the rig was rapidly going over. The derrick had disappeared and so had the radio shack – there had been no time to send out a mayday call. We grabbed our lifejackets and ran; I was just wearing a shirt and trousers and my slippers.

“Initially I went to the highest point on the rig, the helideck, along with a number of other men, but spotting the empty lifeboat, which had been set adrift by the rig lurching, I determined to swim out to it, so went back down to the deck with Colin Grey, a radio operator, who had flown out with me earlier that day. By now the lifeboat was maybe over 100m away, and the sea was very rough with waves over 6m high, and I didn’t think I’d manage to reach it, but Colin was a champion swimmer, so he dived in and I saw him reach the lifeboat and clamber in.

“The deck was now under water and we knew we had to get off fast. A couple of us tried to launch a Carley life-float – the thing that looks a bit like a white torpedo; you pull a rip cord and it inflates into a dinghy. We didn’t think to tie it to the hand rail though, and as it inflated the rig made a further lurch and it went scuttling away over the waves, empty. We crept along the top of the hand rail like tightrope walkers to the next one and managed to get that afloat and three of us climbed in, soon followed by another 10 men. We were about to cut the rope to get away from the rig before she turned over when we saw Bert Cooper, the fitter, appear. He had been in the workshop below decks and broke several ribs when the rig lurched, but had somehow managed to climb in pitch darkness up to the deck. We turned back for him and then started paddling as fast as possible away from the rig. We could see a cluster of men still on the heli-deck, but the rig suddenly turned over and they went down with it.”

Rescued by Cargo Ship

Although the Sea Gem had not been able to send out a distress call, a passing cargo ship, the Baltrover, saw the disaster unfold and had immediately radioed for assistance. By the time the rescue helicopters arrived there was nothing to be seen of the Sea Gem but one of the broken legs sticking out of the water, a mass of debris – and empty life-rafts.

Meanwhile, the Baltrover had steamed towards the stricken rig and with great difficulty picked up the men in Kevin’s overloaded life-raft, which by this time was shipping water fast. “One man was wearing Wellington boots and we used them to bale out the raft, which possibly saved our lives. Now another danger faced us, as the waves were pushing us towards the Baltrover and we were at risk of being crushed against it. We paddled round to the lee of the ship, where the crew threw ropes down to us. One man, Ken Forsythe, grabbed a rope and hung on to it, acting as an anchor to the raft so we could clamber up the rope ladder onto the ship. I still don’t know how he managed it in those huge seas. We also had to help the injured up those swinging ladders; in some ways it was the worst part of the whole experience.”

Thirteen men were lost in the disaster, including Colin Grey, who despite swimming to the lifeboat had died of exposure before he could be rescued. “He was only 19 years old,” adds Kevin, sadly. “Two days later Dean Sutherland, the American specialist who had been in charge of the move, had a stroke and died. I think he blamed himself for the disaster, but it wasn’t his fault. The enquiry into it found that the legs had suffered catastrophic metal fatigue, probably because of the cold water, and had literally snapped.”

Sea Gem’s Legacy

Kevin and the 18 other survivors, some badly injured, returned to shore and were taken to hospital, where he was kept overnight as he had injured his leg, before being sent home. “I arrived back 36 hours after I left home – but my offshore career was over, as my leg was never the same again, and I was off work for six months.”

Kevin stayed with BP, working in maintenance at Eakring, before moving to the Central Generating Board, where for 25 years he specialised in safety matters. In his retirement he became a co-founder and curator of the Dukes Wood Oil Museum in Eakring, which celebrates ‘Churchill’s best-kept wartime secret’: the Dukes Wood oil field which kept the ships and planes working during WWII (see The Yanks are Coming, for the story of Dukes Wood).

The Sea Gem disaster left a legacy to the UK offshore oil industry, as many new rules for operating were made as a result of the tragedy. These included more and better safety equipment, the requirement for an Offshore Installation Manager in overall charge, and a permanent standby vessel close to each rig or platform.

The men who survived the disaster continue to meet regularly, the last meeting being in February 2016, when they commemorated the 50th anniversary of the tragedy, although there are now only three of them left. Kevin says, “It is important that those of us who survived get together to remember the men who died and pay tribute to those who saved us.

“Eh, it was a hell of a day,” he sighs. “Boxing Day and all. I still don’t like Boxing Day, or Christmas much – but, anyway, life has to go on. Have you seen this?” And he hands me a mounted core from the well where Kevin Topham and the men of the Sea Gem found the first commercial hydrocarbons in the UK North Sea. A piece of history.