A Complementary Monitoring Method?

Would you like me to give you a formula for… success? It’s quite simple, really. Double your rate of failure… You can be discouraged by failure – or you can learn from it. So go ahead and make mistakes. Because, remember that’s where you’ll find success. On the far side. Thomas John Watson, Sr. (1874–1956), Chairman and CEO of IBM

In 1962 Markvard Sellevoll at the University of Bergen, together with the Universities of Copenhagen and Hamburg, acquired a refraction seismic survey in Skagerak, south of Norway. The aim of the survey was to prove the existence of sediments in the area. The seismic refraction data clearly showed a low velocity layer approximately 0.4 km in thickness with low seismic velocities confirming sedimentary layers.

The end result of the refraction seismic survey from Skagerak in 1962. Sellevoll interpreted the first low velocity layer below the seabed as a glacial sand layer. The velocity of this layer was estimated to 1,680 m/s.

The Basic Idea

In the early history of exploration geophysics, the seismic refraction method was commonly used, but gradually reflection seismic, as we know it today, demonstrated its usefulness and its ability to create precise 3D images of the subsurface. Hence, the use of refraction seismic – by which we mean looking for waves that have predominantly travelled horizontally when compared to reflected waves – decreased. Here we discuss and show evidence that, although the most accurate 4D seismic results are obtained by repeated 3D reflection seismic surveys, there might be a small niche market for time-lapse refraction seismic. Landrø et al. first suggested this monitoring technique at the SEG meeting in 2004. The figure below, taken from this presentation, shows the basic principle: if the oil that originally filled a reservoir is replaced with water, the velocity in the reservoir layer will change, and hence the refraction angle (and the traveltime) for the refracted wave will also change.

Example showing how refracted waves can be used to monitor an oil reservoir that is gradually getting more and more water-saturated. Velocity changes caused by pressure changes may also be detected this way.

Example showing how refracted waves can be used to monitor an oil reservoir that is gradually getting more and more water-saturated. Velocity changes caused by pressure changes may also be detected this way.

It should be noted that the term refraction, or maybe one should say the way the word is used within geophysics, is not precise. The basic meaning is that if a wave changes direction obeying Snell’s law (sin θ1/v1 = sin θ2/v2) across an interface, the wave is refracted. The portions of the initially downgoing energy refracted along the boundary interface are called critically refracted waves. In this case, θ2 is 90°, implying that the incident angle θ1 must be greater than the critical angle sin θc = v1/v2 for waves to travel along the interface. As the critically refracted wave propagates along the interface, energy is sent back to the surface at the critical angle. We call this returning energy refracted waves or refractions. They are also called head waves since they arrive ahead of the direct wave at large source-receiver distances. When we use the term time-lapse refraction here, we mean that we exploit head waves and in general post-critical or diving waves.

Diving Waves

Diving waves are waves that are not head waves but, due to a gradual increase in velocity with depth, they dive into the subsurface and then turn back again, without a clear reflection event.

A diving wave occurs when the velocity (v) increases linearly with depth (z): v = v0 + kz, where k is the velocity gradient. Using Snell’s law again (sin θ1/v1 = sin θ2/v2), it is possible to show that the ray path will be given as a circle with a radius (R):

R = 1 / pk = v0 / (k.sin θi)

where p is the ray parameter:

(p = sin θi / v0)

and θi is the take-off angle with respect to the vertical axis for the ray.

The figure below shows two examples where the solid black line (k=0.75 s-1) represents a velocity model where the velocity increases more rapidly with depth than the solid red curve (k=0.5 s-1). We observe that in a model with higher velocity gradient, the ray prefers to turn around earlier, so the offset where this ray is observed is shorter. This is exploited in Full Waveform Inversion to determine the low frequency velocity model. We clearly see that diving waves occur at large offsets. A linear velocity model is of course an idealisation, but due to compaction, it is not a bad first order approximation for a setting where the subsurface consists of sedimentary layers.

Raypaths for two diving waves in a medium where the velocity increases linearly with depth. V0 = 2,000 m/s and two different k-values are used. The take-off angle with respect to the vertical axis is 30° for both cases.

Complementary to Reflection

A synthetic seismic shot gather showing baseline data (left). The P-wave velocity of the reservoir layer is changing from 2,500 m/s to 2,450 m/s, and the shot gather on the right shows the difference between the base and monitor shot. The black arrow shows the top reservoir event, and the red arrow on the right plot shows that the strongest 4D signal actually occurs close to the critical offset (which is at approximately 5,000 m).

Both head waves and diving waves need large offsets to be detected, and therefore we often put them into the same category, although they are different wave types. It is also challenging to discriminate between diving waves and head waves in field data, so it is often convenient to put them into the same basket.

From the equation defining the critical angle, we see that to generate a head wave or refracted wave the velocity of the second layer must be greater than that of the first layer or overburden. This is the first of several practical disadvantages in the time-lapse refraction method. Another disadvantage is that the horizontal extension of the 4D anomaly needs to be large enough to be detected by the method. A long, thin anomaly is ideal. In this way, it is clear that the refraction method is complementary to conventional 4D seismic.

References

Hansteen, F., Wills, P.B., Hornman, K. and Jin, L. 2010. Time-lapse refraction seismic monitoring. 80th Annual International Meeting. Society of Exploration Geophysicis, 4170-4174.

Hilbich, C. 2010. Time-lapse refraction seismic tomography for the detection of ground ice degradation. The Cryosphere 4, 243-259.

Landrø, M. 2007. Attenuation of seismic water-column noise – tested on seismic data from the Grane field. Geophysics 72, V87-V95.

Landrø, M., Nguyen, A.K. and Mehdi Zadeh, H. 2004. Time lapse refraction seismic – a tool for monitoring carbonate fields? 74th Annual International Meeting. The Society of Exploration Geophysicists, 2295-2298.

Mehdi Zadeh, H. and Landrø, M. 2011. Monitoring a shallow subsurface gas flow by time lapse refraction analysis. Geophysics 76, O35-O43.

Mehdi Zadeh, H., Landrø, M. and Barkved, O.I. 2011. Long-offset time-lapse seismic: Tested on the Valhall LoFS data. Geophysics 76, O1-O13.

Routh, P., Palacharla, G., Chikichew, I. and Lazaratos, S. 2012. Full wavefield inversion of time-lapse data for improved imaging and reservoir characterization. SEG Expanded Abstracts, 1-6.

Sheriff, R.E. 2002. Encyclopedic dictionary of applied geophysics. Society of Exploration Geophysicists. ISBN 0-931830-47-8.

Sirgue, L., Barkved, O.I., Van Gestel, J.P., Askim, O.J. and Kommedal, J. H. 2009. 3D waveform inversion on Valhall wide-azimuth OBC. EAGE expanded abstracts, U038.

Virieux, J and Operto, S., 2009, An overview of full-waveform inversion in exploration geophysics. Geophysics 74, WCC1-WCC26.

Further reading

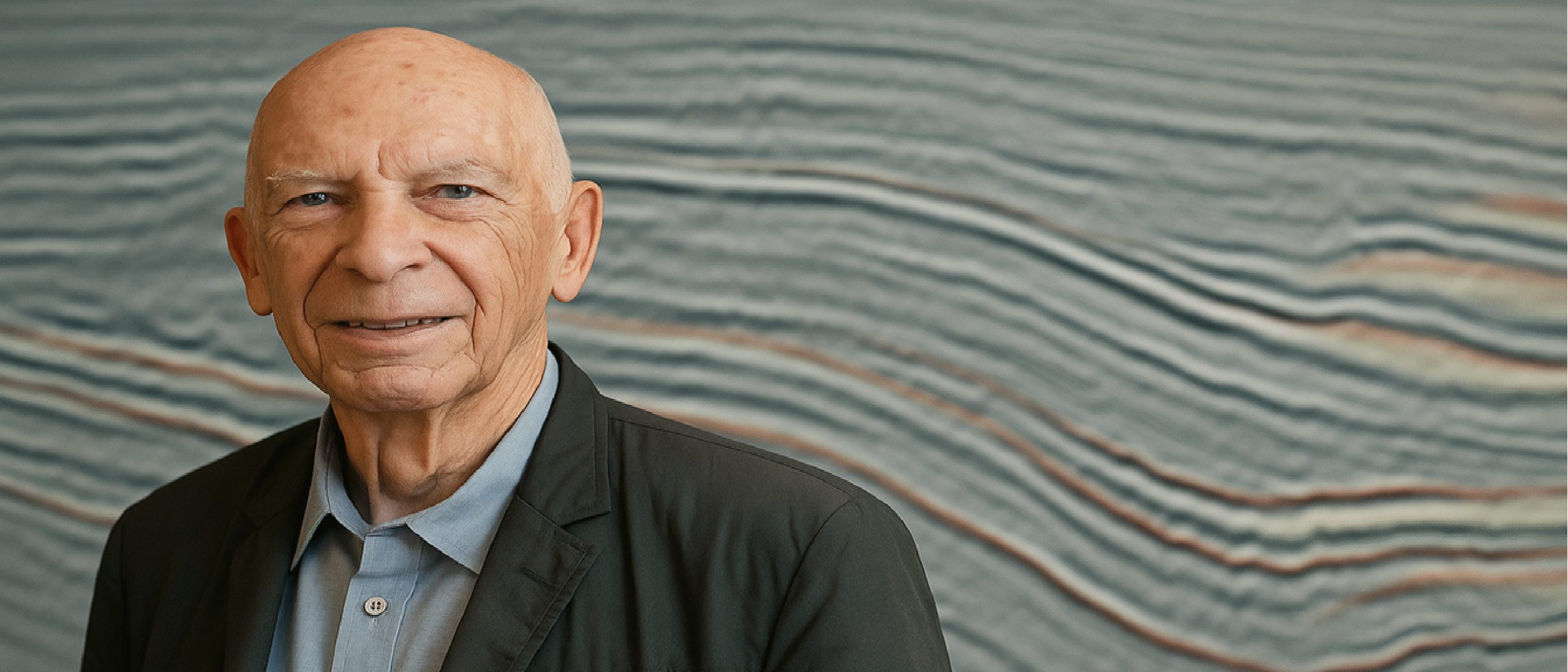

Time-Lapse Seismic and Geomechanics – Part I by Martin Landrø and Lasse Amundsen

Ekofisk, Norwegian North Sea, was one of the first fields where time-lapse seismic proved an excellent tool for monitoring and mapping geomechanical changes in a producing field. This article appeared in Vol. 14, No. 2

Time-Lapse Refraction Seismic II by Martin Landrø and Lasse Amundsen

Field Examples. This article appeared in Vol. 14, No. 4