In that gulf, there was no continental shelf; its waters were not very deep and nowhere exceeded 75 fathoms. The geologists had ascertained that the geological structure of the soil beneath the sea was the same as that of the adjacent territory which contained immense reserves of mineral oil. Consequently fantastic deposits of oil would certainly be discovered. Judge Manley O. Hudson, 1950

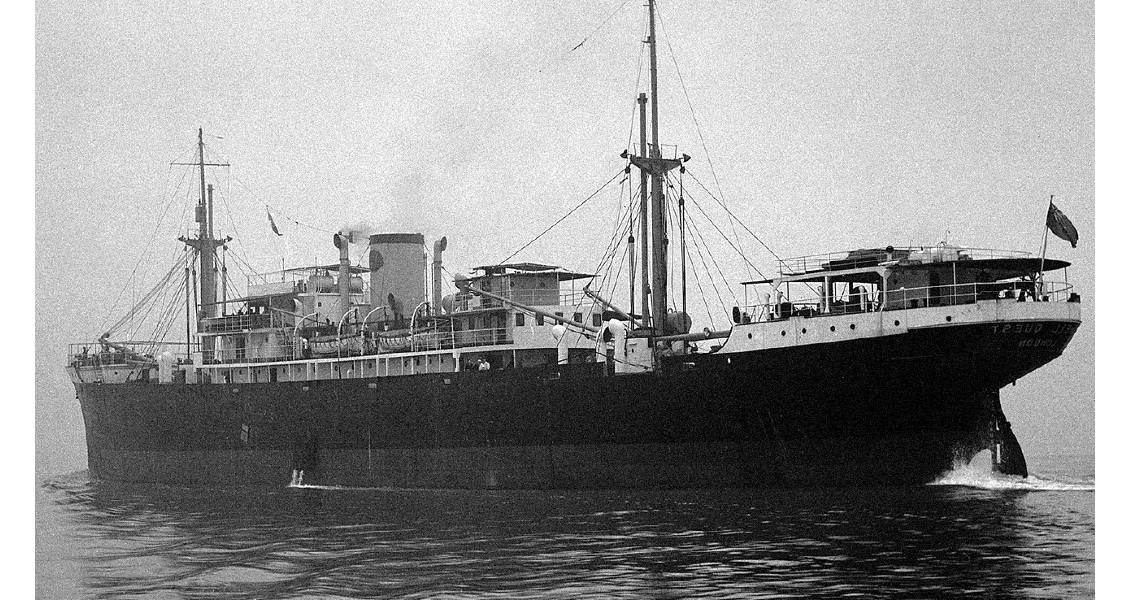

Casting the lead aboard SS Bandra off the Saudi Arabian coast in July 1935. The shallowness of the Arabian Gulf often required soundings to be taken, but also made it highly accessible for oil exploration.The pearl industry, which had once been the mainstay of the Gulf states, was in decline when the first oil was struck on Bahrain in 1932. Discoveries in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait followed in 1938, and Qatar in 1940. It dawned on the oilmen that there was a good possibility of finding oil offshore in the region: the Arabian side of the Gulf has similarities with the Gulf of Mexico, where the modern offshore oil industry began, both having relatively shallow waters conducive to drilling from simple structures or barges.

Casting the lead aboard SS Bandra off the Saudi Arabian coast in July 1935. The shallowness of the Arabian Gulf often required soundings to be taken, but also made it highly accessible for oil exploration.The pearl industry, which had once been the mainstay of the Gulf states, was in decline when the first oil was struck on Bahrain in 1932. Discoveries in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait followed in 1938, and Qatar in 1940. It dawned on the oilmen that there was a good possibility of finding oil offshore in the region: the Arabian side of the Gulf has similarities with the Gulf of Mexico, where the modern offshore oil industry began, both having relatively shallow waters conducive to drilling from simple structures or barges.

After a lull during World War II, interest in offshore exploration revived, spurred on by President Truman’s proclamation of 1945, which effectively extended US jurisdiction over the natural resources of the subsoil and seabed of its entire continental shelf. Similar proclamations followed in 1949 from the rulers of the Arabian littoral, the Gulf sheikhs, in respect of their own seabed resources. But there were serious logistical obstacles to working offshore, since the Gulf sheikhdoms were undeveloped, lacked basic infrastructure and bore no comparison with the commercial environment of the United States at that time. Great Britain was the predominant foreign power in the region, and sought to restrict the access of non-British firms through a network of treaties and undertakings with the local rulers.

In Saudi Arabia, where British influence was waning, the government decided to work with the onshore concessionaire, the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco). In 1939, Dick Kerr, an Aramco geophysicist, had drawn a red arrow on a map of north-east Saudi Arabia, writing alongside: “possible high area offshore”. The arrow pointed out into the Gulf past a hooked spit of white sand called Safaniya, translated as “the place where navigators meet”. In 1949, offshore drilling began there and Kerr’s prediction proved to be correct, with the “high area” indicating the presence of an oil reservoir thousands of feet beneath the seabed. This turned out to be the first of many discoveries in the Gulf – and the largest offshore oil reservoir in the world.

Qatar: Disaster and Discovery

In Qatar, the first offshore concession was granted to Superior Oil of California, a veteran of offshore operations in the Gulf of Mexico, and Central Mining and Investment Ltd, a British company. The company holding the onshore concession, Petroleum Development (Qatar) Ltd, disputed the ruler’s right to grant a concession to the Superior group, claiming that they already held the rights; an arbitration decided the issue in the ruler’s favour. However, Superior Oil withdrew from the venture in 1952, citing ‘financial, political and economic’ difficulties, and the concession went to Shell, another company with offshore experience.

The Shell Company of Qatar was formed in October 1953, with its headquarters at Doha. Undersea surveys began with a converted merchant vessel, Shell Quest, which was used as a base for marine operations and a floating depot for men and equipment. A drilling rig, described as looking like an ‘interstellar radar tower’, soon appeared in the incongruous surroundings of Doha Bay.

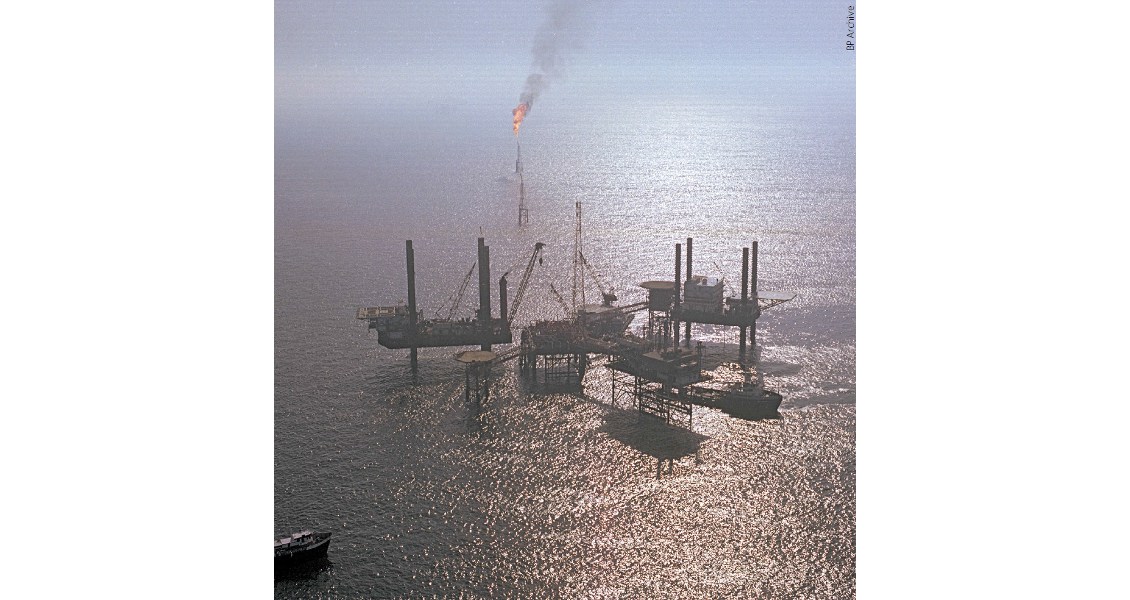

An Aramco offshore drilling rig in 1951.By December 1956, the rig had drilled one well to a depth of 2,042m and had just completed a second one at 3,657m but without finding any oil. Then disaster struck: the rig was being towed to Doha for modifications when the wind changed direction and a heavy crosssea developed. Two 2,000-ton pontoons supporting the platform broke loose and all the lights went out. The platform legs were damaged, the helicopter landing stage collapsed and several Qataris tragically lost their lives.

An Aramco offshore drilling rig in 1951.By December 1956, the rig had drilled one well to a depth of 2,042m and had just completed a second one at 3,657m but without finding any oil. Then disaster struck: the rig was being towed to Doha for modifications when the wind changed direction and a heavy crosssea developed. Two 2,000-ton pontoons supporting the platform broke loose and all the lights went out. The platform legs were damaged, the helicopter landing stage collapsed and several Qataris tragically lost their lives.

The wreck delayed Shell’s operations in Qatar and caused it to review its $21 million investment. In the event, the company decided to persist and the exploration programme was restarted, with successful wells being drilled at Idd al-Shargi (1960) and Maydam Majzam (1963). Oil started flowing in 1964. After the discovery of the massive North gas field in 1972, with a smaller oilfield above, this country of dwindling oil resources was eventually propelled into the top rank of natural gas producers.

Abu Dhabi: Islands in the Stream

In 1953 Sheikh Shakhbut, the ruler of Abu Dhabi (part of today’s United Arab Emirates), granted a 65-year offshore concession covering 30,370 km2 to a subsidiary of British Petroleum (BP), D’Arcy Exploration. The starting point was a geological and hydrographic survey of the seabed conducted by the ocean explorer, Jacques Cousteau, on his research ship, Calypso. In 1954, BP – in partnership with Compagnie Française des Pétroles (Total) – created an operating company, Abu Dhabi Marine Areas Ltd (ADMA). The Sonic, a marine exploration vessel belonging to Geophysical Service Inc, then carried out a seismic survey of the concession area. In 1956, the Astrid Sven arrived on the scene: this was an ageing 1,200-ton freighter once used by the Nazis to refuel their U-boats in the Pacific Ocean. The ship was fitted out with facilities for 30 personnel on board, all the necessary equipment and a drilling platform which was cantilevered over the vessel’s side.

Sheikh Shakhbut, ruler of Abu Dhabi (on left), with his brothers aboard the Sonic in February 1955.Having decided to drill, the challenge was to set up a rig and the infrastructure to support operations. BP drew on technologies from the Gulf of Mexico in the construction of a jack-up drilling platform, the ADMA Enterprise, which was built in Hamburg and then towed to the Gulf. The deserted Das Island became the hub of operations: an airstrip, accommodation and eventually oil storage tanks were built. In 1958, the first oil well was drilled on the old pearling bed of Umm Shaif, striking good-quality oil at 1,676m, followed by further discoveries, including the supergiant Zakum field. In 1962 the first cargo of oil was loaded onto BP tanker, British Signal. In 1972, BP sold a 45% share in ADMA to the Japan Oil Development Company (JODCO).

Sheikh Shakhbut, ruler of Abu Dhabi (on left), with his brothers aboard the Sonic in February 1955.Having decided to drill, the challenge was to set up a rig and the infrastructure to support operations. BP drew on technologies from the Gulf of Mexico in the construction of a jack-up drilling platform, the ADMA Enterprise, which was built in Hamburg and then towed to the Gulf. The deserted Das Island became the hub of operations: an airstrip, accommodation and eventually oil storage tanks were built. In 1958, the first oil well was drilled on the old pearling bed of Umm Shaif, striking good-quality oil at 1,676m, followed by further discoveries, including the supergiant Zakum field. In 1962 the first cargo of oil was loaded onto BP tanker, British Signal. In 1972, BP sold a 45% share in ADMA to the Japan Oil Development Company (JODCO).

Zakum is the biggest oilfield in Abu Dhabi and one of the largest offshore fields in the Gulf – and in the world. It covers an area of about 1,500 km2 and lies in an average water depth of around 20m and consists of an upper and lower reservoir. The ADMA partners decided to push ahead with developing the lower reservoir layers. These had better quality oil and were more productive, since they were at a higher pressure than those in the upper reservoir, which they decided not to develop.

As a result of this decision, two new companies were created: ADMA-OPCO to operate the lower field and the Zakum Development Company (ZADCO) to develop and operate the upper field. The latter company now has three major shareholders: the Abu Dhabi government with a 60% share, ExxonMobil with 28%, and JODCO with 12%.

Dubai: Fields of Good Fortune

In Dubai, after D’Arcy had obtained the first offshore concession in 1954, oil development was put on hold for several years. Finally, in 1966, the Continental Oil Company acquired a 50% share in the concession and drilling began, leading to the discovery of the Fateh (‘Good Fortune’) field. The problem of storing oil in shallow waters was solved by building and transporting large floating tanks, known as khazzans, and towing them to where the oil was produced offshore. As the first khazzan was being towed into position there was a vast bubbling outflow of air along the rear skirt line, with a corresponding amount of noise as air was expelled. In the words of a Continental Oil engineer, it was like a “thunderous belch”.

On 22 September 1969, the first tanker of oil was exported from Fateh Field, thus enabling Dubai to finance a number of massive projects new to the Gulf; this was the start of the modern city of Dubai.

For Sharjah, a protocol agreement with Iran over the disputed Abu Musa Island ensured that, when the Mubarak field was discovered in 1972, its oil would be shared with Iran. This oilfield was found about 35 km east of the island by the Buttes Gas and Oil Company operating through Crescent Petroleum. Initially, the field went on stream at high rates, and other wells tested even higher, but by 1983 production had slumped to 6,400 bopd and to 5,900 bopd two years later.

Drawing Lines on the Sea

Oil exploration gave rise to several disputes between the rulers over their maritime boundaries. Kuwait was in an awkward position: bordered by Saudi Arabia and Iraq, and facing Iran. This led to arguments over maritime boundaries that would fetter oil exploration and development. A dispute between Saudi Arabia and Bahrain over the Fasht Bu Saafa oilfield was settled in 1958 with the former extracting the oil and the latter sharing the proceeds. Qatar and Abu Dhabi argued over Halul Island until two British experts determined that it belonged to the former and the Al Bunduq oilfield was to be shared between them. Dubai and Abu Dhabi were at loggerheads for many years over their maritime boundary, particularly when the Fateh field was discovered, until the matter was settled in 1968.

During the 1930s, an ongoing dispute between Qatar and Bahrain over the Hawar Islands was exacerbated by the prospect of finding oil in the area. The British representative ruled against Qatar and, when it came to delimiting the maritime boundaries in 1947, the UK government confirmed his decision. The dispute was eventually settled by international arbitration in 2001: Bahrain retained the Hawar Islands and Qatar kept Zubarah, part of the mainland to which Bahrain had laid a claim.

More about strategic gain than oil prospects, the dispute between the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Iran over the Abu Musa and Tunb islands was the most serious territorial issue. In 1971, on the eve of the inauguration of the UAE, Iranian forces occupied the islands and claimed them for the Shah. The two Arabian claimants – Sharjah and Ras al-Khaimah – became part of the UAE, which took up the claim on their behalf; but it is unresolved and remains a contentious issue in the region today.