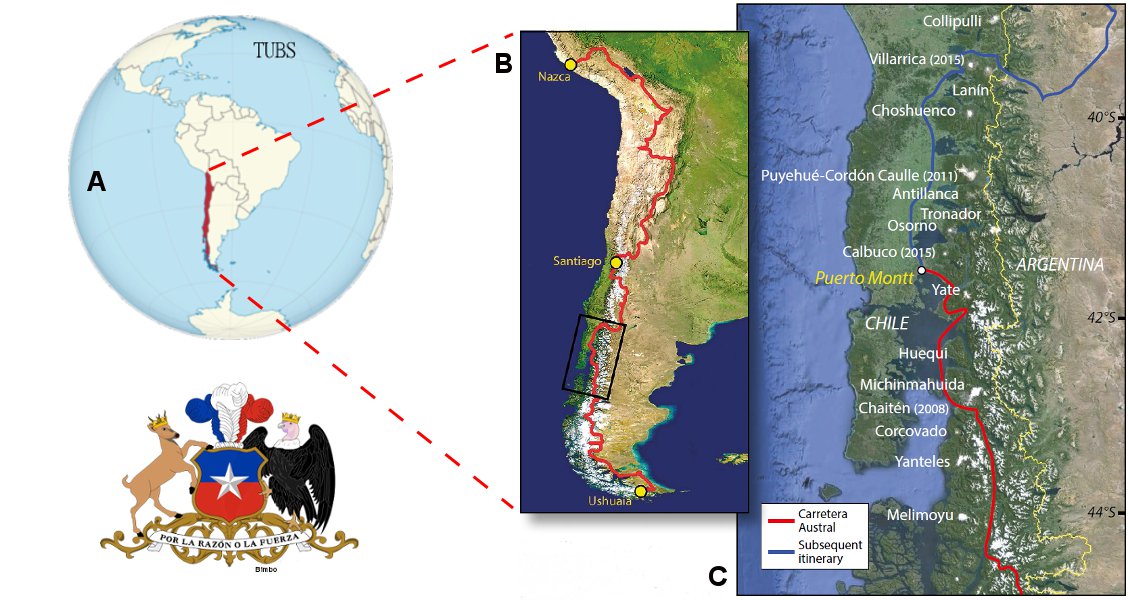

In GEO ExPro, Vol. 12, No. 1, (Torres del Paine – The Patagonian Diamond) Olivier and Caroline described travelling through the dramatic Torres del Paine, in Patagonia, at the start of their 10,000 km epic cycle trip exploring the geological highlights of the Andes. Here they describe another leg of their exciting journey.

This article first appeared as the lead story in Vol. 12. No. 5. For more information, see the ‘Print subscription’ feature at the top of this page.Two months after the start of our journey, we were heading north along Chile’s Road 7, the famous Carretera Austral, which spectacularly meanders between snow-covered peaks and glaciers. The dirt road cut through walls of pristine cold jungle, where hummingbirds were gathering nectar from colourful flowers. Contrasting with this peaceful natural paradise, travellers heading south consistently reported scenes of destruction and desolation from what used to be the peaceful spa town of Chaitén.

This article first appeared as the lead story in Vol. 12. No. 5. For more information, see the ‘Print subscription’ feature at the top of this page.Two months after the start of our journey, we were heading north along Chile’s Road 7, the famous Carretera Austral, which spectacularly meanders between snow-covered peaks and glaciers. The dirt road cut through walls of pristine cold jungle, where hummingbirds were gathering nectar from colourful flowers. Contrasting with this peaceful natural paradise, travellers heading south consistently reported scenes of destruction and desolation from what used to be the peaceful spa town of Chaitén.

Fifty kilometres before reaching Chaitén, a covering of grey ash could be seen toning down the usually sparkling glaciers. Many trees were dead on the slopes of the mountain. The river beds were filled with ash, as were the sides of the road. When we reached Chaitén, an unforgettable scene hit us in the stomach: Chaitén was a partially destroyed, abandoned town, buried under a gloomy grey ash, and dominated by a monstrous volcano that continuously vomited a gigantic gas cloud.

Chaitén: an Unexpected Eruption

Early in the morning of 2 May 2008, the Chaitén volcano exploded. Numerous earthquakes had shaken the area for several days before the eruption, warning the authorities and the population of the small coastal town, but because the volcano had no reported historical activity and did not show any recent signs of unrest, the authorities expected that it was the massive volcano Michinmahuida, 25 km east of the town, which was preparing an eruption. What a terrible surprise the inhabitants of Chaitén had, therefore, when a gigantic explosion occurred just 10 km away in the hills overshadowing the city.

House partly buried in ash in Chaitén. (Olivier Galland, Géoroute)As soon as the eruption started, the local population was evacuated. At its climax, the eruption produced an impressive Plinian ash column, 30 km high. Miraculously, this did not devastate the immediate surroundings, as the dominant west winds pushed the ash cloud across South America, eventually reaching Buenos Aires and the Atlantic. The ash also settled in the vicinity of the volcano, covering the area with a fine grey blanket, which rainfall then turned into the characteristic volcanic mudflows known as ‘lahars’. Even though the eruption had not succeeded in destroying the town, the lahars obliterated numerous buildings and split the town in two with a wide, grey area of no-man’s-land. Fortunately, by this time Chaitén had been emptied of people.

House partly buried in ash in Chaitén. (Olivier Galland, Géoroute)As soon as the eruption started, the local population was evacuated. At its climax, the eruption produced an impressive Plinian ash column, 30 km high. Miraculously, this did not devastate the immediate surroundings, as the dominant west winds pushed the ash cloud across South America, eventually reaching Buenos Aires and the Atlantic. The ash also settled in the vicinity of the volcano, covering the area with a fine grey blanket, which rainfall then turned into the characteristic volcanic mudflows known as ‘lahars’. Even though the eruption had not succeeded in destroying the town, the lahars obliterated numerous buildings and split the town in two with a wide, grey area of no-man’s-land. Fortunately, by this time Chaitén had been emptied of people.

We camped on what used to be the seashore. The volume of ash carried by the lahars was such that a new, vast ash delta now filled the bay, moving the coast more than a kilometre seaward. Instead of the dark blue waters of the Pacific Ocean, a monotonous grey landscape spread in front of us. Partly buried boats and houses, including the former tourist information office, protruded from the deposits, breaking the monotony of the delta.

But the most impressive feature of this surreal scenery was the volcano. Only 10 km away, it dominated the bay and the valley. We could not forget it for a single second: it was visible from everywhere in the town – a chaotic, reddish volcanic dome that constantly exhaled dark gases and vapours. The summit was gradually growing, and from time to time unstable sections collapsed and produced small ash clouds. The volcanic dome had formed because the lava erupted by Chaitén was very viscous, and consequently could not flow downslope as in Hawaii but accumulated at the vent. In Chaitén, numerous blocks of porous, light pumice ejected by the volcano covered the ground. It is noticeable that the erupted magma was of rhyolitic composition, making this the first major rhyolitic eruption in nearly a century (the last one occurred at Novarupta, Alaska, in 1912). The 2008 eruption of the Chaitén volcano is thus a natural laboratory for such eruptions.

Because the road was partly destroyed further north, we left Chaitén by boat, travelling to the small fishing harbour of Hornopiren, before heading to Puerto Montt. Less than ten days later, Chaitén’s volcanic dome collapsed, producing pyroclatic flows that ran furiously down the slopes of the volcano. They miraculously stopped at the gate of the town, but after this the Chilean authorities abandoned Chaitén.

A String of Stratovolcanoes

After a few days’ rest at Puerto Montt, we cycled north through Chile’s Lake District, where during the ride we could often identify the characteristic topography of the volcanic arc.

The most majestic of the volcanoes is Osorno, a perfect ice-capped, steeply pointed cone. This shape is characteristic of stratovolcanoes, which are typically found in active margins, i.e. in subduction geodynamic settings. Other famous examples of stratovolcanoes are Mount Fuji, Japan, and the almost perfect Mayon Volcano in the Philippines. They form as a result of successive effusive and explosive eruptions of basaltic, andesitic to dacitic magmas, producing stratified competent lava flows and loose tuff layers, respectively. The southern volcanic zone of Chile hosts many volcanoes that recently hit the headlines after large eruptions, including Puyehue-Cordón Caulle (2011) and Calbuco (2015).

Climbing Villarrica

Villarrica, rising 2,847m above sea level, is a characteristic stratovolcano with an almost perfect conical shape. Its volcanic output primarily comprises compact basaltic lava flows, andesitic lava and pumice layers. Some locals like to claim that it is the most beautiful volcano in the world, and its majesty is enhanced by the 40 km2 of glaciers that crown its summit, they may well be right.

It is not usually possible to climb Villarrica without a guide, but we obtained special permission directly from the director of the Villarrica National Park, don Jorge Paredes, to climb it alone. In return, we promised to visit him after the climb to report our observations. But he warned us not to have too many expectations: there was currently no lava in the crater…

We started our ascent at 4am in full darkness under the stars, which was really enjoyable. After an hour’s walk through the forest, we reached the end of the national park road at the very foot of the volcano and of the base of the Villarrica ski resort. Even in the darkness, the almost perfect conical shape of the volcano was clearly visible. Suddenly, a pale red glow issued from the crater: did you say “No lava”, Mr. Paredes?

As we climbed the steep slope of the volcano, the stunning sunrise revealed wonderfully memorable scenery, with the volcano Llaima to the north and the triangular shadow of Villarrica stretching in front of us. After several hours’ climbing we stopped for a short break and looked down at the vehicles of the guided groups of tourists far below our promontory. We were much higher than them, and we were amused by their late start, sure that they could not catch up with us. But we were much less amused when we realised that their vehicles had clustered at the start of a ski lift, that this lift was working and that it exited… only 50m below us! We quickly packed and went on, but a few minutes later, the lift liberated hordes of fresh, loud visitors, who were almost running up the mountain. Tired after our early morning climb, we could not keep up and, as we looked on miserably, they overtook us on the glacier, a few hundred metres before the summit.

Luckily, the guided groups only stayed a very short time at the summit before returning to the valley, so after a while, we had the volcano to ourselves. We were sitting on the rim of the enormous crater, which was so deep that its bottom was invisible; it really made us feel we were looking into the mouth of the Earth. Sulphur gas was exhaling from every pore of the ground, comfortably heating up the area we were sitting on. Periodically, we noticed that gas burst out of the centre of the crater, accompanied by rumbling and subtle vibrations in the ground. There was no doubt: lava was venting at the bottom of the crater, which explained the glowing red light we had seen in the darkness. Our observations were confirmed in subsequent months, as the crater filled with lava and the vents became visible from the crater rim.

Chile’s Most Active Volcano

Basaltic ropy-flow-type (pahoehoe) lava flow near summit of Villarrica. (Olivier Galland-Géoroute)The long descent down the volcano was very enjoyable. The ground was made of loose volcanic lapilli that allowed us to run comfortably without hurting our knees. When we got back down to Pucón, the tourist town at the foot of Villarrica, we reported our observations to Mr. Paredes, who was really excited that there was lava in the crater, as it is good for the tourist industry. However, at the same time he said that he regretted that people, and especially the locals, tended to forget that Villarrica is Chile’s most active volcano and that Pucón and its surroundings are built on the pyroclastic deposits of the volcano. He clearly remembered the frightening 1971 eruption, which melted the snow and part of the glacier, liberating massive lahars that destroyed villages at the foot of the volcano. The landscape still exhibits prominent scars of these lahars on the volcano flanks.

Basaltic ropy-flow-type (pahoehoe) lava flow near summit of Villarrica. (Olivier Galland-Géoroute)The long descent down the volcano was very enjoyable. The ground was made of loose volcanic lapilli that allowed us to run comfortably without hurting our knees. When we got back down to Pucón, the tourist town at the foot of Villarrica, we reported our observations to Mr. Paredes, who was really excited that there was lava in the crater, as it is good for the tourist industry. However, at the same time he said that he regretted that people, and especially the locals, tended to forget that Villarrica is Chile’s most active volcano and that Pucón and its surroundings are built on the pyroclastic deposits of the volcano. He clearly remembered the frightening 1971 eruption, which melted the snow and part of the glacier, liberating massive lahars that destroyed villages at the foot of the volcano. The landscape still exhibits prominent scars of these lahars on the volcano flanks.

To make tourists aware of the volcanic hazards, Pucón has designed an original warning system based on green, orange and red lights, very similar to traffic lights. Since 1971 this volcanic hazard alert system has remained in the ‘green’ level, the system becoming more part of the tourist attraction package than an educational and hazard communication medium. The year 2015 interrupted this long quiescent period, as Villarrica started a new eruptive cycle, which resulted in loud explosions and evacuation of the population in the nearby communities. This new eruption has been going on for several months already.