‘This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands…’

William Shakespeare, King Richard II, Act 2 scene 1

When Shakespeare wrote of the ‘silver sea’ defending England’s ‘precious stone’, recognizing the importance of Britain’s maritime waters to the health and wealth of the ‘sceptred isle’, he could not have imagined the riches that lay under the waves, particularly those hostile waters of the North Sea. Nearly 400 years would have to pass before those treasures, buried deep beneath thousands of feet of unseen rock, would be revealed. Now, 50 years on from the first oil and gas discoveries in the North Sea we celebrate this golden anniversary by looking back at this important center of oil and gas production, set in silver but often turbulent seas.

A Long and Varied History

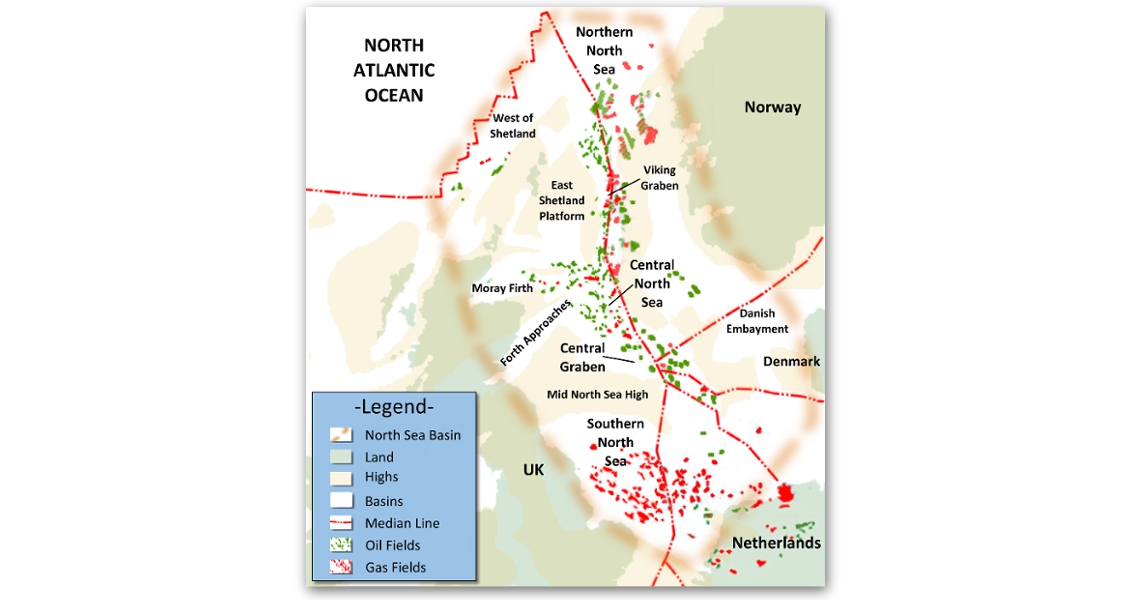

The North Sea (Figure 1) is an epicontinental sea located on the north-western European continental shelf and is a diverse maritime province that has provided bountiful riches to the people that inhabit her coastal stretches and far beyond. With a long and varied geological history (see inset box below) the North Sea has undergone multiple changes in shape and extent. Today the rhomb-shaped embayment stretches more than 600 miles (970 km) in length and around 360 miles (580 km) in width, an area of 290,000 square miles (750,000 km2), with an average water depth of 300ft (90m).

For hundreds of years before the discovery of oil the North Sea was plundered for her other treasure – fish. That industry continues and although this busy seaway serves as a major shipping route, tourist destination and as the site for renewable wind and wave energy projects, marine wildlife continues to live, if not necessarily thrive, in and around the region.

Hostile and Unknown

During the 1950s and 60s the oil industry had accumulated a wealth of experience developing offshore reserves in places like Venezuela and the Gulf of Mexico, but the relatively small size of fields in and around the North Sea had not attracted companies to this ‘hostile and higher-cost’ area. However, with the ratification of the ‘Continental Shelf Convention’ in 1964 and assigning of territorial rights to mineral resources along a median-line, halfway between participating countries, plus recognition of the ‘giant’ status of the onshore Groningen gas field (The Netherlands), the search for other, analogous fields in the offshore was about to begin.

Figure 2: The Ill-fated Sea Gem, which made the first UKCS discovery, was a converted steel barge, supported on 10 steel legs 15m above the waves. (Source: BP)Geophysical exploration was able to proceed in advance of petroleum legislation but drilling activities in the North Sea would only begin with the 1st Round of UK licensing late in 1964, with The Netherlands, Denmark, Germany and Norway quickly following. Interest in the 1st Round was so great that government departments could not keep up with applications and companies were asked to form consortia to speed things up; there were even tales of bids being decided by the toss of a coin! A total of 53 licenses were awarded – 394 blocks, 22 consortia, 51 companies. In the early days the ‘majors’ and the US independents led the way, with only 30% of the companies applying for licenses being UK-based.

Figure 2: The Ill-fated Sea Gem, which made the first UKCS discovery, was a converted steel barge, supported on 10 steel legs 15m above the waves. (Source: BP)Geophysical exploration was able to proceed in advance of petroleum legislation but drilling activities in the North Sea would only begin with the 1st Round of UK licensing late in 1964, with The Netherlands, Denmark, Germany and Norway quickly following. Interest in the 1st Round was so great that government departments could not keep up with applications and companies were asked to form consortia to speed things up; there were even tales of bids being decided by the toss of a coin! A total of 53 licenses were awarded – 394 blocks, 22 consortia, 51 companies. In the early days the ‘majors’ and the US independents led the way, with only 30% of the companies applying for licenses being UK-based.

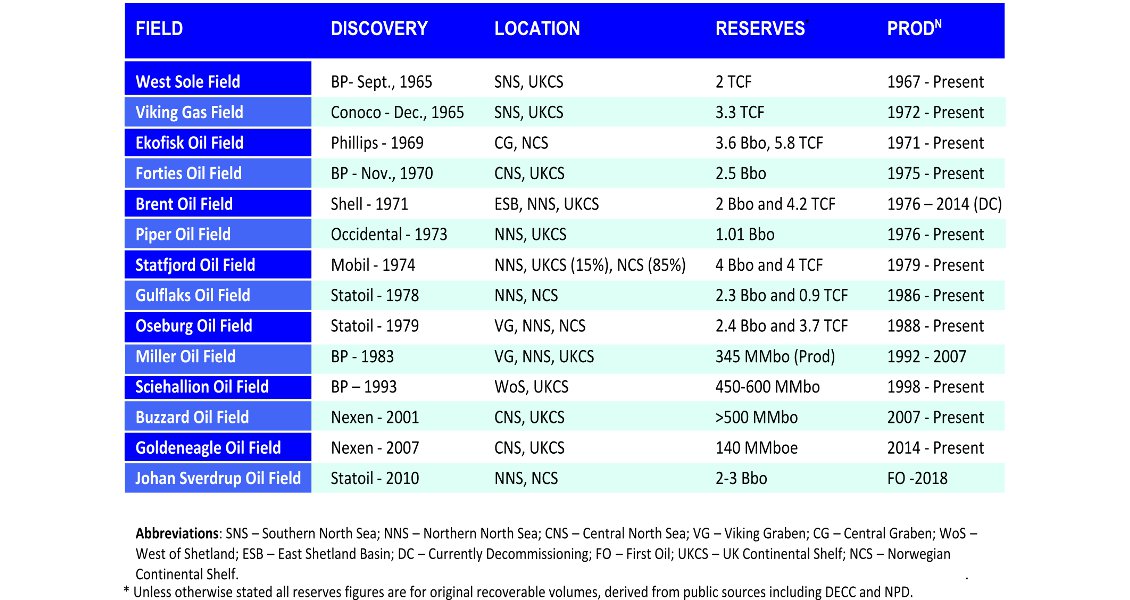

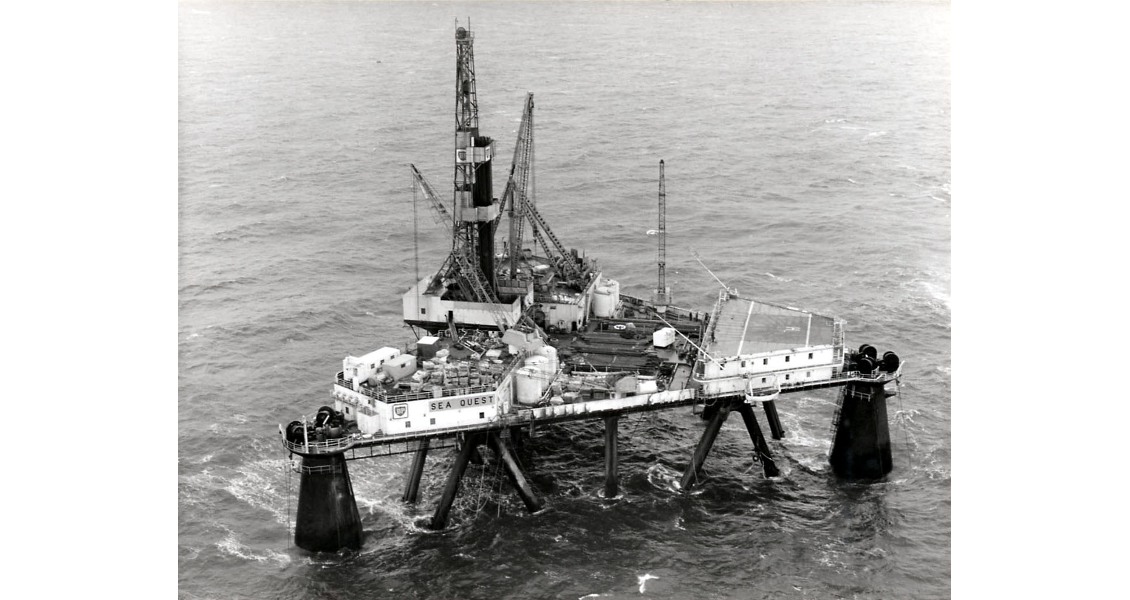

The first wells were dry but data gained proved invaluable and late in 1965 BP made the first discovery of commercial quantities of gas in a Groningen analog close to the UK, in what was to become the West Sole Gas Field. The drilling rig was the now infamous Sea Gem and the good news quickly turned somber as reports that the rig had collapsed as it was moving out to drill a new well began to make headlines (Figure 2). Two of the legs became detached and the platform plunged upside down to the bottom of the sea. It was two days after Christmas, 1965 and thirteen men were killed.

A short time after the discovery at West Sole, Conoco announced the discovery of the Viking Field (Table 1) and the excitement behind the exploration campaign began to intensify. A 2nd Round was announced in the UK in 1965, this time for 1,000 Blocks – although participation was not as great as for the 1st Round, mostly because the initial work programs were still active and limited human resources were available. News of discoveries from both Rounds followed at regular intervals and the oil rush had begun, with giant fields like those at Ekofisk and Forties convincing geologists that greater rewards could be had in the relatively uncharted Central and Northern provinces.

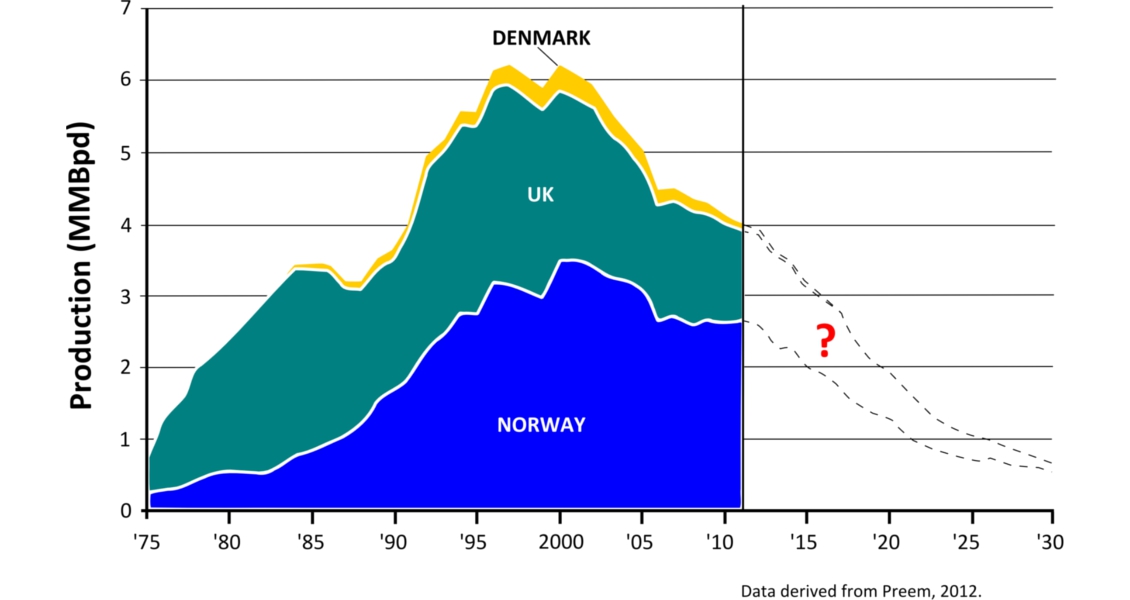

By the time of the 4th Round ‘Scramble’ in 1971 the introduction of ‘spec surveys’ in the North Sea heralded the start of a new phase of development, and within a few years most of the major oil and gas accumulations in both the Northern and Southern North Sea had been discovered and production levels began the rapid incline towards peak production, occurring sometime around 1999/2000 (Figure 3).

Following the early, exciting years of intense exploration activity, the 1980s saw steady but interrupted development and addition to reserves, as the region became subject to the cyclical nature of the industry. By the 1990s the region moved into another phase of exploitation and in 1992 BP discovered Foinaven, the first deepwater oilfield to be developed in the UK and the first development West of Shetland.

In the early part of the 21st century production and reserves additions are in inevitable decline but with imaginative technical and commercial models there are always new opportunities. In 2011, for example, BP sanctioned development of Clair Ridge using ‘LoSal’ enhanced recovery technology and in 2014 sanctioned a life extension project for the Magnus field. Smaller independents specializing in late field exploitation also have an important role to play and continue to enter the changing business landscape.

50 Years and Counting

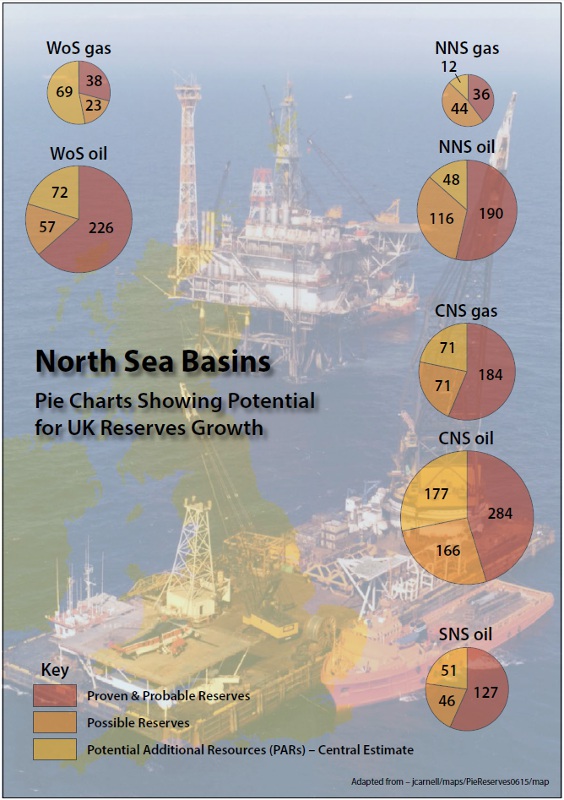

Figure 6: North Sea Basins: potential for reserves growth 2015. Key: Gas – billion cubic metres; Oil – million tonnes. (Source: Modified from jcarnell www.gov.uk.) Background image is the Forties Alpha installation (Source: BP).In 2015 the UK is in the 28th Round, Norway the 23rd and a series of initiatives are being implemented with a view to stimulating exploration and development activities in the region generally and in predefined areas or sectors. Around 40 Bboe have been produced in the UKCS alone and government estimates suggest that there could be another 24 Bboe to recover – another 30–40 years of production (Figure 6). Regionally, production is in a steady decline and, in a climate of diminishing returns and to a backdrop of challenging decarbonization targets, global financial markets will decide the future for North Sea oil and gas; regulators can only do so much.

Figure 6: North Sea Basins: potential for reserves growth 2015. Key: Gas – billion cubic metres; Oil – million tonnes. (Source: Modified from jcarnell www.gov.uk.) Background image is the Forties Alpha installation (Source: BP).In 2015 the UK is in the 28th Round, Norway the 23rd and a series of initiatives are being implemented with a view to stimulating exploration and development activities in the region generally and in predefined areas or sectors. Around 40 Bboe have been produced in the UKCS alone and government estimates suggest that there could be another 24 Bboe to recover – another 30–40 years of production (Figure 6). Regionally, production is in a steady decline and, in a climate of diminishing returns and to a backdrop of challenging decarbonization targets, global financial markets will decide the future for North Sea oil and gas; regulators can only do so much.

Initiatives such as the Wood Review are now in the early phase of implementation and the UK is looking to recover the maximum value from North Sea investments. In Norway the sovereign wealth fund – Government Pension Fund Global, valued at $785 billion in September 2013 – will buffer the effects of diminishing North Sea revenues for future generations in Norway. ‘One day the oil will run out, but the return on the fund will continue to benefit the Norwegian population’ reads the blurb, and informed sources will tell you that 50% of the reserves are still in the ground and ‘the era of oil… is not over yet.’

In 1967 BP constructed a terminal in Yorkshire and ‘within 18 months North Sea gas was igniting an energy revolution that changed the face of Britain’. Barring any sudden change in commodity prices, or the rapid evolution of some new enabling technologies, the North Sea is unlikely to have the same impact on fortunes in the future. The glory days are gone but the region will continue to provide energy of one sort or another, as long as there is a market for it. The current impact of the industry downturn on North Sea fortunes will make themselves clearer as taxes and royalties dry up and unemployment in the region rises, so the North Sea will feature large in the public conscience for a while longer.

In the immediate future the industry will look to begin to decommission many of the 450+ installations that have been in use for the past 40 years, including 10,000 km of pipelines and around 5,000 wells. Decommissioning expenditure is projected to be £19 billion by 2030, rising to £23–25 billion by 2040.

Final Word

The ‘silver sea’ has given up her bounty at a cost that is greater than can be measured in dollars alone. An army of men gave their lives in the pursuit of the North Sea’s oil and gas, with the tragic events at Piper Alpha and the loss of 167 lives in July 1988 providing the nadir. Their sacrifice has been to our great collective benefit and their memory and legacy must shine bright and long. As we look to the next 50 years of the industry in the North Sea it is imperative that we honor them by ensuring that such tragedies remain a thing of the past.