To say there is concern over the industry’s rising capital expenditure is an understatement. ‘Capital discipline’ is the new in-phrase. The headline-grabbing challenges of more difficult geology and political disruptions have been exacerbated by scarcities of experienced and qualified staff, painful surges in key exchange rates and several large-scale blighted projects.

Many would say the underlying factor has been a level of complacency among the major producers fueled by the price surge of the mid-2000s. The facts are that the costs of oil and gas extraction have risen almost 11% per year since 1999, reaching a high-point of $700bn in 2013 and out-pacing revenues by 2 – 3%. Rising capex has not been matched by rising production. Although there has been an increase of 11.9 MMbpd since 2000, the bulk of the capex increase has been post-2005, a period in which conventional oil production has almost flat-lined.

Oil Prices Are Key

Most new production is reliant on a high break-even oil price – between $70 and $100, a 20% increase since just 2011. During the same period the average Brent price has actually dropped approximately $5. Over the last thirty years, companies have become used to an average cash return of around 11% but levels are now below this, forcing companies to consider whether they can generate sufficient funds to service existing dividend and investment commitments.

In an economist’s ideal world, oil prices should rise. However, they have been remarkably stable over the last two years, as US shale production has filled some of the demand gap. Even if prices do rise, companies face the conundrum that a level much above $100 appears to be counterproductive. There is a limit to what even OECD consumers can bear and, as the price spike of 2008 demonstrated, demand from marginal consumers – those that have some degree of flexibility over how much they consume – can pull back dramatically. Not only do high oil prices suppress individual demand but they also sap economies, removing the ‘feel good’ factor and capping growth, preventing any possible lift-off in general consumption.

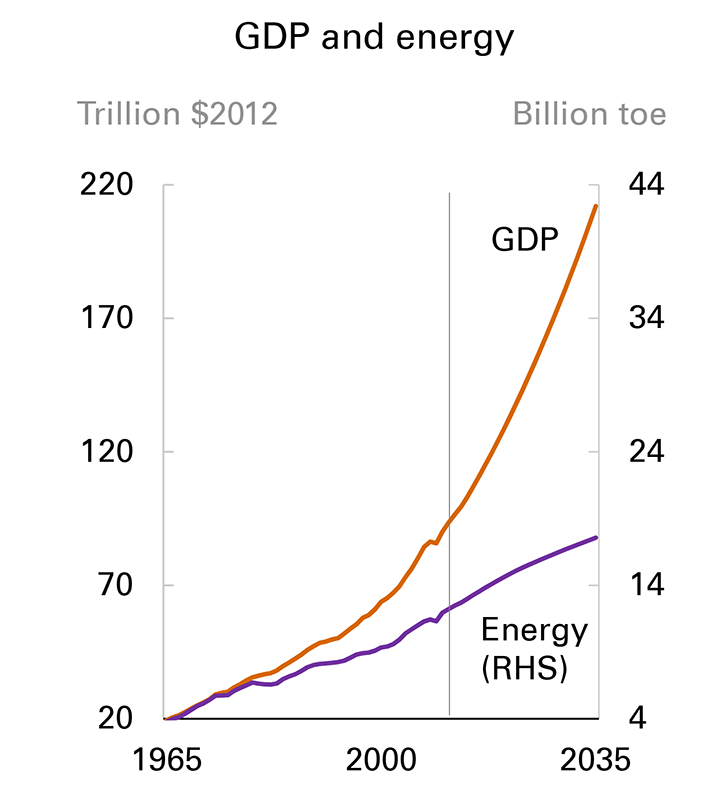

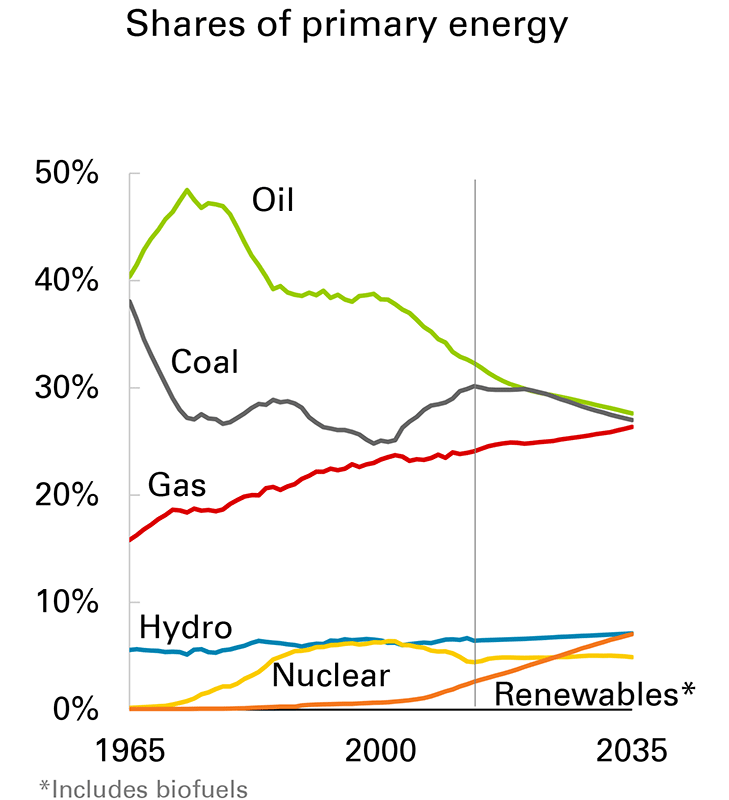

Energy is gradually decoupling from economic growth. BP Energy Outlook 2035The result is that investors are looking nervous. Even the best performing majors – ExxonMobil and Chevron – have seen their shares rise only 11% in the period 2011 – 2014, while the Standard and Poor 500 index has risen 40%. Shell has actually dropped 2%. Adding to investor fears of poor returns, a growing fossil fuel divestment campaign has been gaining traction and several new benchmarks have been developed that specifically exclude oil and mining companies. The concern is that discoveries in the Arctic or ultra-deep water may simply become stranded assets with development either not justified by the oil price or ruled out by regulators and governments focused on ‘unburnable carbon’. In April this year BlackRock, the world’s biggest fund manager, announced its own collaboration with London’s FTSE group and it is rumoured that investors as large as Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund are considering divestment from the sector.

Energy is gradually decoupling from economic growth. BP Energy Outlook 2035The result is that investors are looking nervous. Even the best performing majors – ExxonMobil and Chevron – have seen their shares rise only 11% in the period 2011 – 2014, while the Standard and Poor 500 index has risen 40%. Shell has actually dropped 2%. Adding to investor fears of poor returns, a growing fossil fuel divestment campaign has been gaining traction and several new benchmarks have been developed that specifically exclude oil and mining companies. The concern is that discoveries in the Arctic or ultra-deep water may simply become stranded assets with development either not justified by the oil price or ruled out by regulators and governments focused on ‘unburnable carbon’. In April this year BlackRock, the world’s biggest fund manager, announced its own collaboration with London’s FTSE group and it is rumoured that investors as large as Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund are considering divestment from the sector.

In response, the oil majors have created a buyers’ market with a mass sell-off of more than $300bn of assets, as well as a commitment to cutting costs. The major buyers of physical assets appear to be private equity, sovereign wealth funds and the commodity houses that have been moving beyond trading into investments all along the supply chain.

Future Prospects

BP Energy Outlook 2035There is little consensus on what happens next. If the shale boom peaks in the early 2020s, supply shortages could become a more pressing reality with the world increasingly dependent on Middle Eastern oil. Whether prices will then rise enough to allow more expensive, high break-even point investment depends on the extent to which economies have recovered from the current slump – as well as the alternatives developed in the meantime. The IEA is predicting prices $15/b higher than current levels by 2025 and annual investment of $850bn by the 2030s. However, 90% of oil investment will simply be compensating for declines in existing fields, keeping production at current levels; similarly 70% of gas investment will be maintaining the status quo.

BP Energy Outlook 2035There is little consensus on what happens next. If the shale boom peaks in the early 2020s, supply shortages could become a more pressing reality with the world increasingly dependent on Middle Eastern oil. Whether prices will then rise enough to allow more expensive, high break-even point investment depends on the extent to which economies have recovered from the current slump – as well as the alternatives developed in the meantime. The IEA is predicting prices $15/b higher than current levels by 2025 and annual investment of $850bn by the 2030s. However, 90% of oil investment will simply be compensating for declines in existing fields, keeping production at current levels; similarly 70% of gas investment will be maintaining the status quo.

Controlling costs is easier said than done. Undoubtedly the world will continue to need oil and gas, but upstream companies are looking less than comfortable. Inevitably they will continue to face challenging questions from investors for the foreseeable future.