If one word could sum up the Mediterranean island nation of Malta, it would be ‘limestone’. Limestone has shaped the islands’ topography, their economy and possibly black bank accounts. It has also made Malta, and particularly the island of Gozo, a paradise for carbonate geology studies – and diving.

In this article, I will take a look at them all. But, let’s start with the (literally) fundamentals: the geology itself. Get ready to get nerdy!

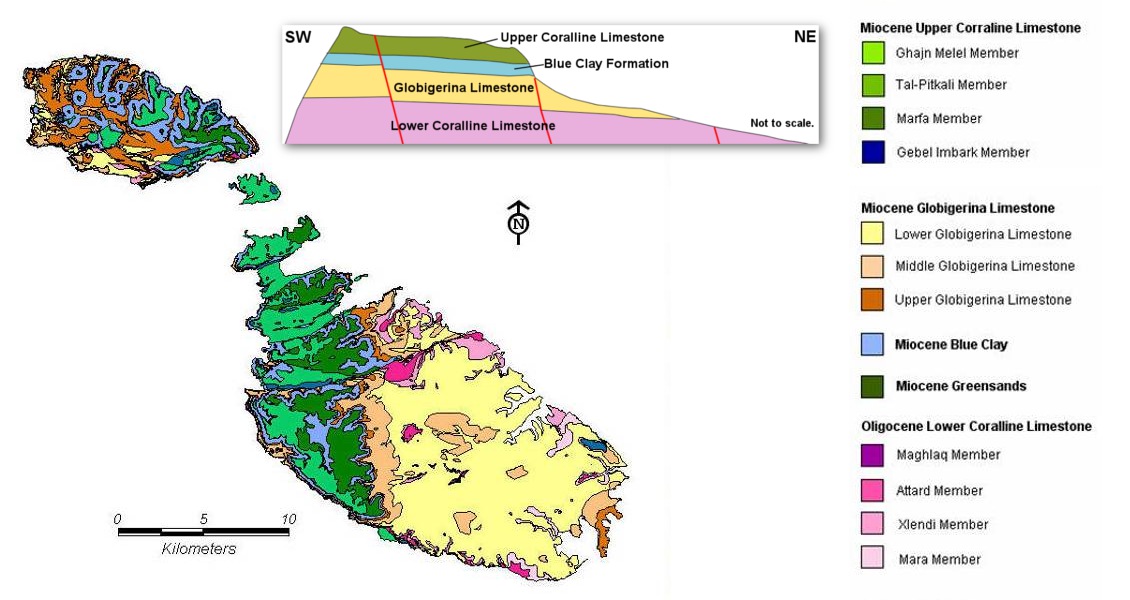

Malta lies on a large carbonate platform that stretches northwards from Africa and also includes Sicily. Geo-wise, Malta is thus a part of Africa, and the islands are just the youngest tops of the rocks that peak above sea surface. They were deposited from the Upper Oligocene through Upper Miocene, from about 20 to 8 million years ago. On the geological time scale, Malta is a toddler.

The lithostratigraphy on Malta is divided into three main groups, their development controlled by changes in the sea level of the Mediterranean through time. Sea level, in turn, is the result of the complex interplay between how much water came through the Gibraltar strait relative to evaporation, and sediments dumped from the erosion of landmasses lifted up when Africa collided with Europe to produce the Alps.

Lower Coralline Limestone

The lower of the three levels is the Lower Coralline limestone, made up of carbonate sand and gravel, mixed with shell fossils. The carbonate sediments were originally living organisms, such as coral reefs, shells, or as very fine-grained plankton – probably on what is now Sicily. These rocks were then eroded, flushed south to Malta by high-energy waves and currents, and re-deposited as sand and gravel in shallow water. Some beds in the Lower Coralline consist nearly solely of shell fossils, ground to fragments by the eternal wave movements.

The Lower Coralline limestone is hard and resistant to wear and tear, and forms steep and vertical cliffs along the coast. North-west of Marsalforn on Gozo, it has beautiful crossbeds, where each bed consists of thin layers that dip in the direction of the current.

The Globigerina Limestone

The middle interval, the Globigerina limestone, is the softest of the three limestones. It is composed nearly completely of planktonic carbonate, and gets its name from the Globigerina foraminifera, a very tiny crustacean. Pure and fine-grained, this limestone has a distinctive yellow-greyish colour. It is used to construct buildings, aquaducts, pavements – basically everything – and Maltese towns therefore have the same yellowish-greyish colour from tip to toe. Because limestone slowly dissolves from acids in rain, some buildings have had parts of their walls washed away.

The limestone is pure because it was deposited in deep water, probably 200m, where very few organisms would mess it up before it consolidated into rock.

However, periods of shallower water interrupted the deep calmness, and with shallow water came organisms that buried in the sediments. Their burials and tunnels, ‘bioturbation’ in geo-speak, left coarse dark nodules that almost entirely make up some beds. My muggle – a.k.a. non-geologist – travel mates were quite surprised to learn that the dark blobs in the light rock were literally old faeces from slimy creatures that lived in the sediments before they became hard rocks; they ate not-yet-solidified carbonate rock through one end, and left brown blobs at the rear.

The longer a layer is left in shallow water, without being buried by new sediments, the more time the creatures have to make burials. In the bay of Marsalforn, our base at Gozo, one can see how a homogeneous limestone gets more and more burials, ending in a layer that is nearly entirely made up of burial nodules – before the sea level suddenly rose again, and the rocks abruptly changed back to yellowish again.

Upper Coralline Limestone

Above the Globigerina is the thin Blue Clay. It is the softest rock on Malta, but very important, because it consists of very fine-grained particles of clay minerals and carbonate, which make it impermeable. It catches water that sinks down through the porous rocks above, and forms the floor of a precious freshwater table.

Finally, the Upper Coralline limestone is a lookalike, although thinner, of its older sibling, deposited in the same high-energy deposition environment. On Gozo, this hard limestone stands out as caps with steep cliff sides and flat tops, above the softer rocks beneath. Therefore, castles for defence were built on top of these high parts of the island. Actually, after an Arabian pirate attack in 1556 kidnapped nearly the whole population, for a long time the remaining Gozitans stayed inside the citadels at night and went out only to work on the fields during the day.

By now, you have already seen glimpses of how the geology of Malta influences people’s lives. Let’s take a closer look.

Few Natural Resources

Water has always been scarce on dry Malta. It sinks through the porous limestone, and therefore the country depends on ground water. The largest fresh water body is at sea level, in the Lower Coralline, where lighter fresh water floats on salt water, but heavy use of the ground water has seriously threatened the future of the fresh water supply. Fresh water is also obtained through reverse osmosis of ocean water, but this energy-intensive, oil-fuelled process costs five times as much as ground water, and therefore many illegal wells tap into the ground water reservoir. As a result of the water scarcity, Malta produces only around one fifth of the food it consumes.

Malta has no natural resources. No metamorphism or volcanism circulated fluids saturated with metals. No ore, no coal, no geothermal, no energy resources. Sicily, with the famous Mt. Etna and other active and extinct volcanic fields, lies just to the north, and the volcanic island of Pantelleria to the south-west – but on Malta, nothing.

How about oil? Malta lies on the Pelagian block, a northward extension of Africa that also includes large oil fields on Sicily. Just to the west is Tunisia and to the south is Libya, both well known for their large resources. Thus, there is no reason why Maltese waters could not hold hydrocarbons. The first exploration well, Naxxar 2, was drilled onshore back in 1959. Altogether 12 wells have been drilled, both on and offshore. Offshore Alexia 2 found oil in 1984, while onshore MTZ 1 was a gas discovery in 1999. These were both technical discoveries but important, as they proved a working petroleum system.

In recent years, a number of oil companies have obtained acreage offshore Malta, looking into deeper and older rocks than those exposed on the islands themselves, but which are analogues to fields in Libya, Tunisia and Sicily. The most recent, Hagar Quim 1, was drilled south of Malta in 2014 by Genel Enerji and its partner Mediterranean Oil and Gas. It targeted a Lower Eocene to Paleocene carbonate-clastic reservoir but unfortunately came out dry. Upper Cretaceous reefs, and structural traps on Late Triassic-Early Jurassic platforms are other potential targets.

It is tempting to link some Maltese businesses to the lack of natural resources. The Maltese have become a prominent shipping nation – and a tax haven. At least, Malta has avoided the curse of natural resources!

A Diving Paradise

Swimming in the Blue Hole. (Source: Karsten Eig)Finally, let’s, literally, dive into one of the lighter sides of Maltese life: that under water. Malta, and especially Gozo, is regarded as the best place to dive in the Mediterranean. Malta has protected its fish stock fairly well, so there is plenty to see. Karst caves and sinkholes along the coast create spectacular landscapes above and below the water. Among them, the Cathedral Cave is a huge dome with access only underwater. Breaking the surface inside the cave, the dome is illuminated by the sun’s rays coming through small openings in the wall. Any sound, word or wave echoes from the walls. Then comes the swim out again, through the large, mighty door opening into the big blue yonder.

Swimming in the Blue Hole. (Source: Karsten Eig)Finally, let’s, literally, dive into one of the lighter sides of Maltese life: that under water. Malta, and especially Gozo, is regarded as the best place to dive in the Mediterranean. Malta has protected its fish stock fairly well, so there is plenty to see. Karst caves and sinkholes along the coast create spectacular landscapes above and below the water. Among them, the Cathedral Cave is a huge dome with access only underwater. Breaking the surface inside the cave, the dome is illuminated by the sun’s rays coming through small openings in the wall. Any sound, word or wave echoes from the walls. Then comes the swim out again, through the large, mighty door opening into the big blue yonder.

Even more spectacular is the Blue Hole. It is a sinkhole, where the sea has also torn away the lower part and connected it to the sea. The upper part is hard and consists of a well-cemented fossil rich layer, and creates a natural rim around the deep pool. A popular escape destination, the Blue Hole is chock full of bathers in the upper part and divers at all levels.

Just close by is the Azure Window, standing on a pillar in the sea. Once probably a cave, now only one last pillar is standing. It was an amazing experience to dive into the big Blue Hole, and see the shadow of the arch above, with waves smashing onto the pillar. Below the arch, the sea floor was covered with boulders that had fallen down from it during the winter season, a reminder that the pillar is slowly being eroded away. Geology may look eternal, but it certainly is not…