In Victorian times, there were many reports in the United Kingdom of oil and gas seepages accidentally discovered while coal seams and railway tunnels were being excavated – but developing commercial oilfields was an entirely different matter. Although the Scottish shale oil industry was established and lasted over a hundred years, it would take two world wars to kick-start conventional oil production.

The Shale Oil Industry

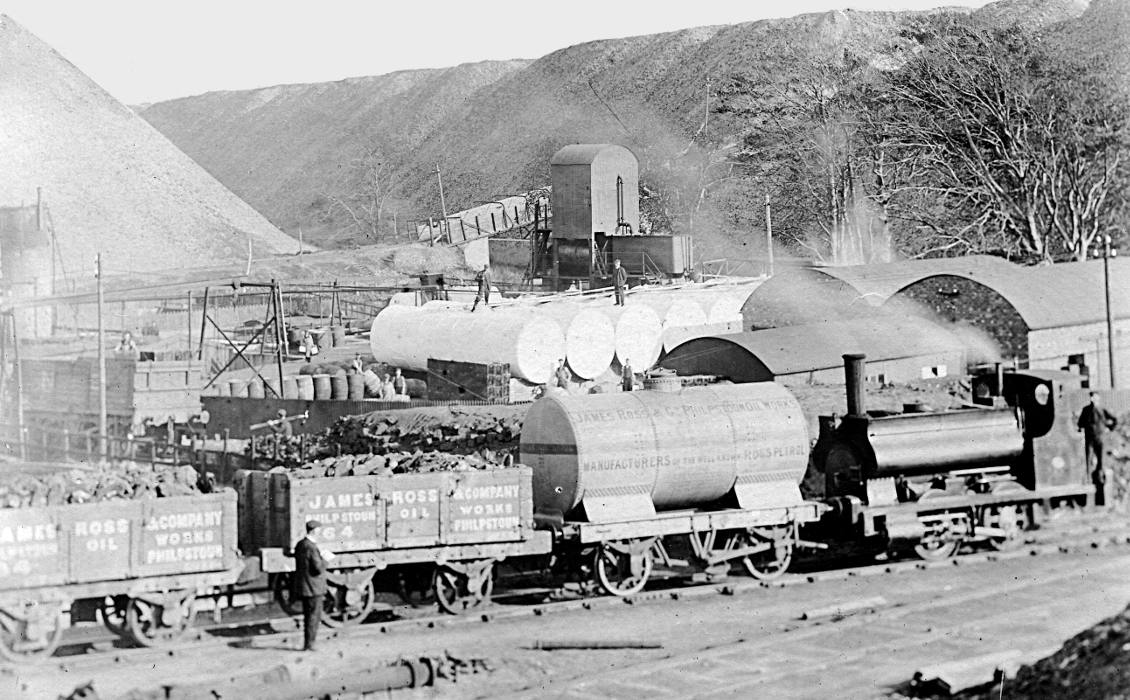

From the 1850s, Scottish companies used devices called retorts to produce oil from cannel coal (a type of bituminous coal) using a process known as pyrolysis. This involved heating the coal and capturing the evaporated liquid so that it could be sold as petroleum products.

As supplies of cannel coal depleted, Scottish entrepreneur James ‘Paraffin’ Young began applying the same processes to shale, producing oil which was then refined into various products: candles, and lamp lubricating and burning oils. In 1863 he bought a new complex at Addiewell, West Calder, near a shale deposit. As if to emphasise the pioneering spirit of the age, the corner stone of the new building was laid by Henry Morton Stanley, the famous African explorer – Young was a generous benefactor of Stanley’s expeditions.

This was the start of Scotland’s first oil boom, the ‘oil mania’ years. At first, the best seams yielded up to 40 gallons of oil per ton of shale. Mass production was established, with shale being processed at 130 sites across Scotland and, although most of these were short-lived, the industry was the UK’s only significant oil producer for many years. Production reached a peak in 1913 when over 3.2 million tons of oil shale were processed, but by then the average yield was 20 gallons per ton and production was expensive: East Lothian shale oil was more than double the price per ton compared with Persian oil, including freight.

By 1920, the Anglo-Persian (later Anglo-Iranian) Oil Company had acquired the remaining Scottish shale oil companies and created Scottish Oils Ltd in order to run them as a consolidated enterprise. Despite a brief reprise during World War II, production gradually declined and operations ceased in 1964.

In England, progress was sporadic and uncertain. In 1787 Shropshire miners had struck a bitumen spring, the famous Tar Tunnel, from whence oil was sold for treating ropes, caulking decks and medicinal purposes. In 1848 James Young created products from crude oil at the Biddings colliery in Derbyshire. Kimmeridge Clay, the main North Sea oil source rock, outcropped in a less mature form in eastern and southern England, and was worked in Dorset for many years. Several large consignments of shale were sent to Scotland for processing, but no lasting industry emerged. The oil shales of Norfolk prompted much speculation during the fuel scares of World War I, but interest dwindled after the war when it was discovered that the oil had a high sulphur content, and was therefore without commercial value.

A Very Fine Show

The conversion of Royal Navy ships from coal to oil, and the demands of World War I, put great stress on the nation’s oil supplies. By 1917 the situation was critical. Scottish shale oil could not meet wartime demands, and foreign oil supplies were vulnerable to attack. As fuel stocks dwindled, the government investigated ways of increasing oil production at home. One answer was to look for sources of conventional oil on the UK mainland.

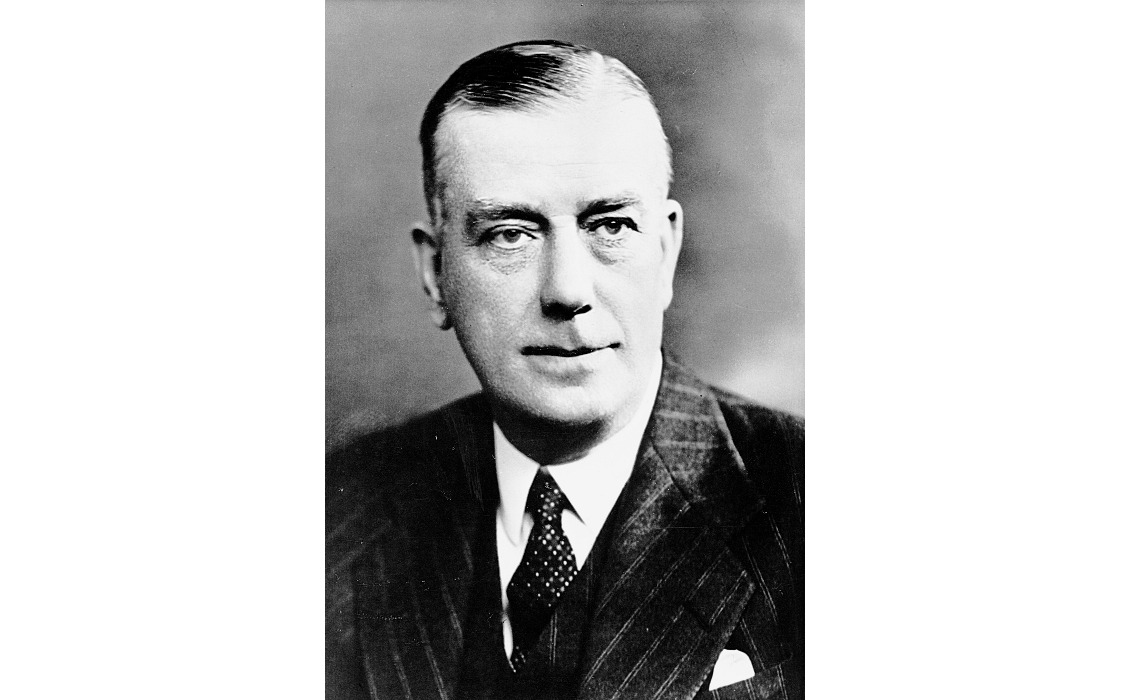

The conversion of Royal Navy ships from coal to oil, and the demands of World War I, put great stress on the nation’s oil supplies.Two figures emerge from a confusing scene: John Cadman, the technician and government adviser, who was knighted for his efforts; and Lord Cowdray, the oil magnate, who was convinced that oilfields might be found in the UK. As director of HM Petroleum Executive, Cadman chose the first 15 onshore drilling areas and Cowdray’s firm, Messrs Pearson and Son Ltd, was contracted to manage the sites, including one at Hardstoft in Derbyshire.

The conversion of Royal Navy ships from coal to oil, and the demands of World War I, put great stress on the nation’s oil supplies.Two figures emerge from a confusing scene: John Cadman, the technician and government adviser, who was knighted for his efforts; and Lord Cowdray, the oil magnate, who was convinced that oilfields might be found in the UK. As director of HM Petroleum Executive, Cadman chose the first 15 onshore drilling areas and Cowdray’s firm, Messrs Pearson and Son Ltd, was contracted to manage the sites, including one at Hardstoft in Derbyshire.

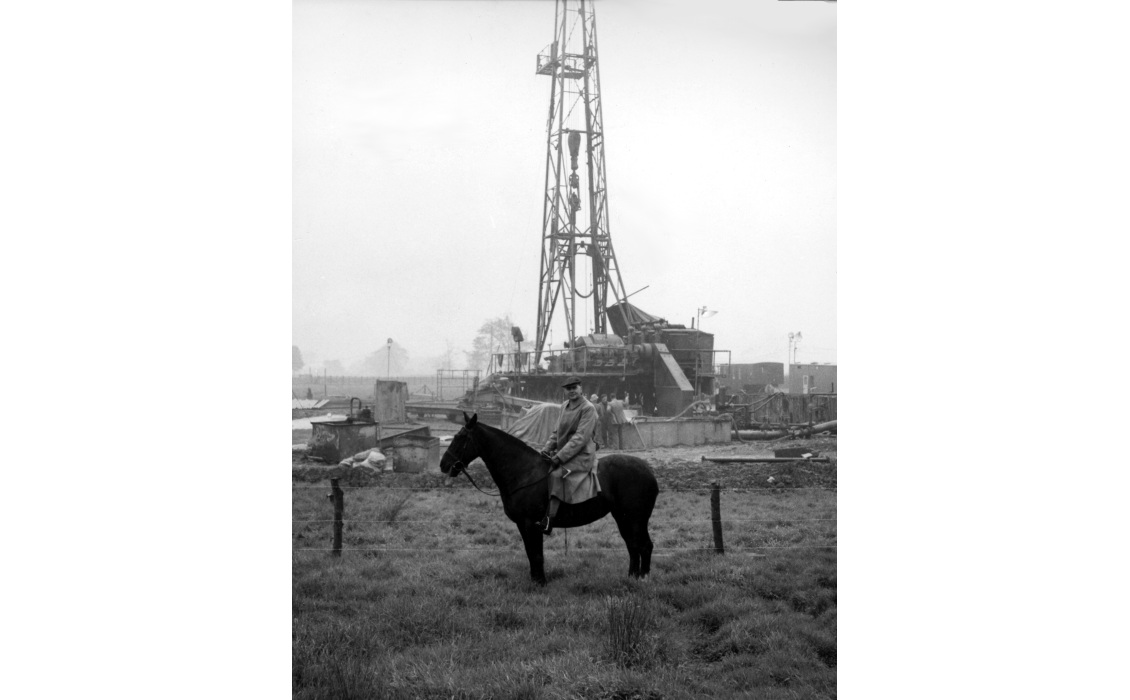

British firms could not perform the necessary drilling operations, therefore plant, equipment and 40 ‘brawny’ drillers were brought over from the United States. Using a cable drill rig, they struck oil at Hardstoft on the night of 27 May 1919 in the Carboniferous Limestone at a depth of approximately 1,000m. According to press reports of the time, the drillers called it ‘a very fine show’. A year later, oil flow was estimated at 50 barrels a week, and its quality was considered to be on a par with high grade oil from Pennsylvania.

Government indifference and legal difficulties stalled this first wave of drilling. The programme had been dogged by arguments over who owned the oil: was it the Crown (i.e. the country) or the landowner? At Hardstoft, the oil was kept in a tank pending a decision. A Petroleum Production Bill, which would have settled the issue, was defeated in the House of Commons by Labour MPs who objected to royalties being paid to landowners. The Defence of the Realm Act, which allowed the government to enter land for the purpose of oil exploration, lapsed. This was not exactly what Lord Cowdray had in mind: ‘I had expected a Rockefeller fortune,’ he told the House of Lords.

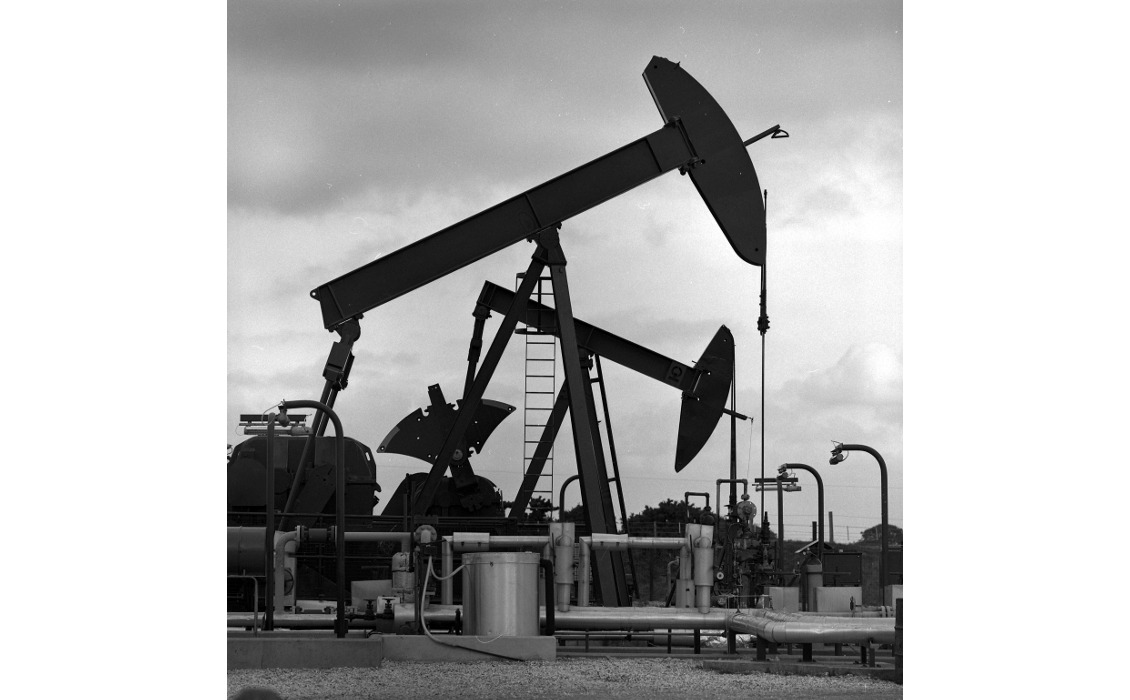

It fell to Lord Devonshire, the owner of the Hardstoft site, to take over drilling operations there. After a work-over and with a nodding donkey pump installed, the well reached a flow of 8 bopd and then went into decline. Nevertheless, it continued to produce commercial oil until 1945, sending it by rail to a refinery in Scotland. Of the ten other wells in the original programme, five had oil shows. A well drilled in the Midland Valley of Scotland by an Anglo-Persian subsidiary, the D’Arcy Exploration Company, produced the best result with seven tons of oil, but all of these wells were abandoned when the government withdrew its support.

Secrets of the Forest

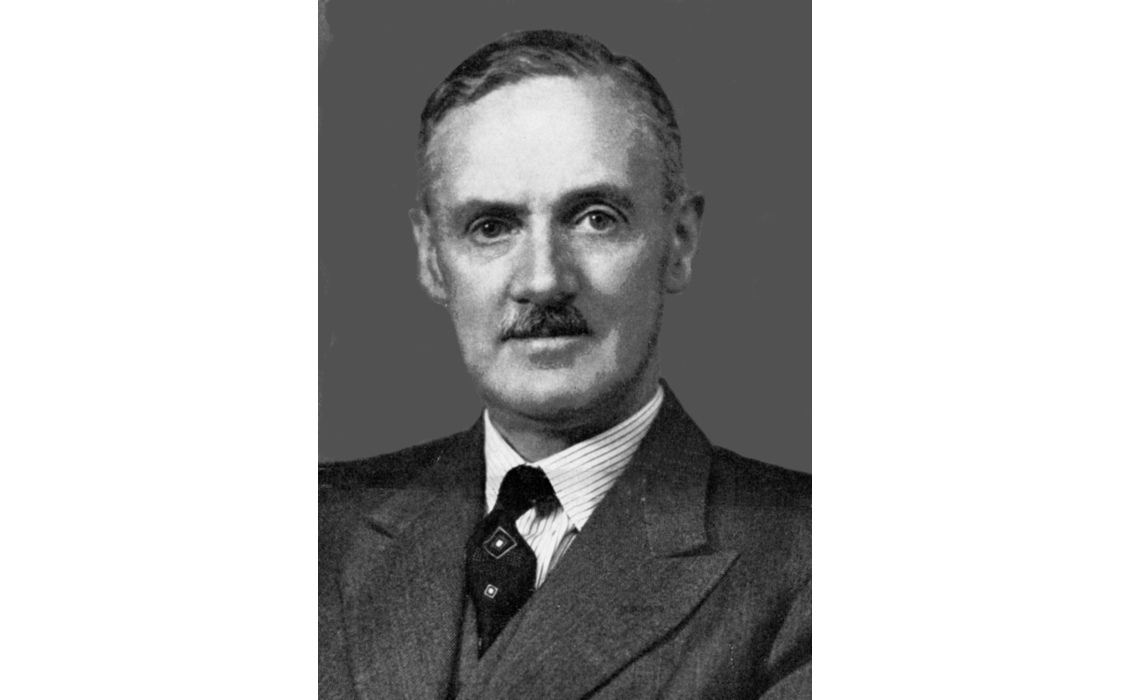

The Petroleum Production Act of 1934 nationalised the country’s oil resources and triggered a fresh search for onshore oil. A key figure in this was George Martin Lees, chief geologist of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (forerunner of BP). Lees had a keen scientific mind and expounded geological theories that often defied conventional wisdom. He struggled to persuade his company to invest in UK exploration, so he invited a sceptical Sir John Cadman, then chairman of the company, to visit some bituminous sandstone outcrops on the Dorset coast in the Wessex Basin. According to Lees, it was only after Cadman sat down and found his trousers stuck to the softened bitumen that the argument was won.

D’Arcy Exploration gained the first exploration licences. Over the next ten years, the company drilled 95 exploratory wells, many close to known seepages. A subsidiary of Standard Oil (New Jersey) found a small oilfield in the Midland Valley in 1937, followed closely by D’Arcy, which found gas in the same vicinity. In May 1939 D’Arcy discovered a small oilfield at Formby in Lancashire, followed by a larger oilfield at Eakring, Nottinghamshire, in the heart of Sherwood Forest. The oil was of good quality, with a specific gravity from 0.83 to 0.89 from a depth of 583m. D’Arcy went on to discover new oilfields at nearby Kelham Hills and Caunton, and even took over the Hardstoft well and improved its flow of oil.

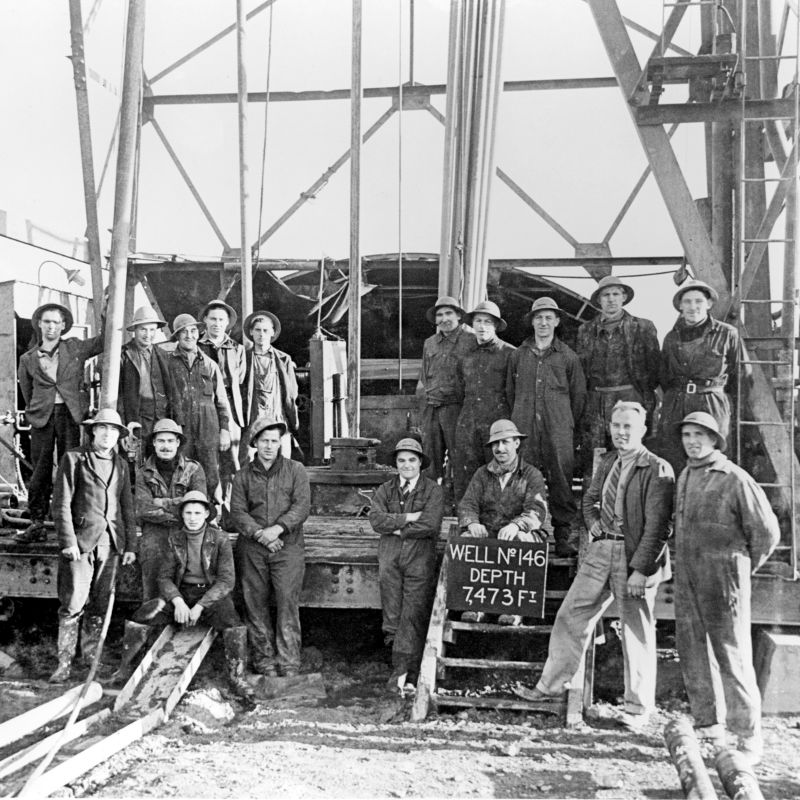

Workers at Well No. 146, Duke’s Wood. (BP)The advent of war in 1939 brought a striking parallel with the earlier conflict. A submarine blockade brought fuel shortages, and by August 1942 only two months’ worth of oil remained in stock. The government introduced a ‘short haul’ policy to obtain oil from sources closer to home. The UK now had oilfields, but most officials were unaware of their existence – when Sir Philip Southwell of D’Arcy raised the issue at a meeting of the Oil Control Board, members of the audience were astounded. ‘What oilfields?’ they asked.

Workers at Well No. 146, Duke’s Wood. (BP)The advent of war in 1939 brought a striking parallel with the earlier conflict. A submarine blockade brought fuel shortages, and by August 1942 only two months’ worth of oil remained in stock. The government introduced a ‘short haul’ policy to obtain oil from sources closer to home. The UK now had oilfields, but most officials were unaware of their existence – when Sir Philip Southwell of D’Arcy raised the issue at a meeting of the Oil Control Board, members of the audience were astounded. ‘What oilfields?’ they asked.

A production target of 100,000 tons per year was set, a massive increase on the 25,000 tons a year then being achieved. US companies were contracted to supply the necessary drilling equipment, including jack-knife rigs and a crew of 42 ‘roughnecks’, who arrived in England under conditions of great secrecy – curious locals were told that they were making a John Wayne movie. These men drilled 106 wells in the Eakring area over the next 12 months, and their efforts ensured that the company achieved its target by September 1942.

Wytch Farm

The oilfields of mainland Britain.In 1959, the UK was producing 80,000 tons of oil from its East Midlands fields. BP Exploration (formerly D’Arcy) was based at Eakring and in charge of the company’s UK operations. Although there were several post-war discoveries in the East Midlands, it was the Wessex Basin that proved the most promising prospect.

The oilfields of mainland Britain.In 1959, the UK was producing 80,000 tons of oil from its East Midlands fields. BP Exploration (formerly D’Arcy) was based at Eakring and in charge of the company’s UK operations. Although there were several post-war discoveries in the East Midlands, it was the Wessex Basin that proved the most promising prospect.

In 1937 Lees and his colleague, Percy Cox, had delivered a groundbreaking paper to the Geological Society entitled ‘The Geological Basis of the Present Search for Oil by the D’Arcy Exploration Co. Ltd.’ Using their knowledge of whaleback anticlines in Iran, they identified the Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous in southern England for exploration. Anticlines at Portsdown, Henfield and Kimmeridge were tested but it was not until 1959 that oil was discovered in commercial quantities. The Kimmeridge No. 1 well produced oil from a Middle Jurassic reservoir and raised hopes of more discoveries to come, but they had to wait until 1974, when the Gas Council in partnership with BP discovered an oilfield in the Lower Jurassic Bridport Sands beneath Wytch Farm. This well was producing some 5,500 bopd in the mid-1980s, by which time BP had taken a controlling share.

The real breakthrough came when further drilling led to the discovery of oil in the Sherwood Sands formation at 1,585m, which was producing an additional 65,000 bopd by 1992. This oilfield is the largest onshore oilfield in Europe (see Wytch Farm Ploughs Ahead), and provided 84% of UK onshore production (as at the end of 2010). The use of extended reach drilling enabled BP to drill offshore wells from a site on the Goathorn Peninsula and, in June 1999, well M16 set a new world record by breaking the 10 km barrier for horizontal displacement distance.

Back to the Shale

The search for oil in the UK tells us as much about human nature as about geology. Oilfields were traditionally associated with warmer climes and the idea of striking oil on the mainland was often greeted with disbelief. Even when onshore oil was discovered, it seemed to stop at the shoreline. The industry only began to make connections between onshore oil and the hydrocarbon potential of the North Sea after the discovery of the Groningen gas field in The Netherlands in 1959. Although the UK was recognised as a significant onshore producer following the Wytch Farm discoveries, the industry kept a relatively low profile. The future may be different, however, with hydraulic fracturing bringing shale oil and gas exploration under the public spotlight. The ghosts of the early shale oil pioneers, if they exist, would certainly be taking note.

Rail tankers transporting crude oil from UK oilfields. (Kevin Topham c/o BP)

Rail tankers transporting crude oil from UK oilfields. (Kevin Topham c/o BP)