The volcanic origin of the Canary Islands is evident everywhere. Best known is the Pico del Teide, the mighty 3,718m tall active stratovolcano that rises above Tenerife, which last erupted, through a flank cone, in 1909. On Lanzarote, the Timanfaya national park encompasses a moon landscape of craters, formed during a long series of eruptions from 1730 to 1736. The last onshore eruption in the islands took place on La Palma in 1971, and a submarine eruption occurred south of El Hierro in the winter of 2011–2012.

The Canary Islands are located on the south-western end of a hotspot trace marked by seamounts that stretch in a gentle, anticlockwise arch along the African coast. The youngest volcanism is in the south-western islands of La Palma and El Hierro, while Lanzarote and Fuerteventura are the oldest Canary Islands at around 24 million years (ma.). Through submarine seamounts it is possible to trace volcanism back to the Lars seamount, around 69 ma. old. Notably, the Portuguese island of Madeira, which last erupted a few thousand years ago, is the south-western end of a similar hotspot track, which leads back to the 67 ma. Ormonde seamount.

Volcanism has moved back and forth along the hotspot tracks and in between the islands, indicating that the plumes have not been entirely stable, and may possibly be influenced by crustal structure along the African passive margin.

Eternally Green Forest

But let’s leave both large scale tectonics and the busy tourist places behind, and go to a small island, just to the left of Tenerife: La Gomera, known as the green pearl of the Canaries. However, it may not look too green upon arrival in the capital San Sebastian, as the southern part of the island is a half desert of eroded volcanic rocks. But drive an hour, to the mountains and the northern side of the island, and an emerald paradise unveils – a thick, green, leafy forest where birds sing to the playful sound of running streams. This is the Laurissilva forest, eternally green and the life blood of the island. Laurissilva is unique, a humid subtropical evergreen forest, almost a rainforest. During warm and humid Cenozoic periods, such forests covered large parts of southern Europe. Today, with a dry climate dominating the Mediterranean area, the Laurissilva is limited to the Atlantic Macaronesian islands (a collective name for the Canaries, Madeira, Azores and Cape Verde islands). A total of 75 different plant taxa have been described as unique to the Gomeran Laurissilva forest, and it also contains 280 species that are only found in the Macaronesian islands.

At one time subtropical forests like the Laurissilva forest covered much of southern Europe. (Karsten Eig)The Laurissilva forest is green not primarily as a result of rainfall, as the dry semi-deserts on the Canary Islands can testify. Instead, it catches the moisture which is carried to the island with the trade winds, which eternally blow from the humid north, touch the Canaries and then cross the Atlantic towards the Caribbean. In the morning, the mountains on the northern side of Gomera are often covered in fog – more reminiscent of a mystic place where hobbits could appear than a subtropical island.

At one time subtropical forests like the Laurissilva forest covered much of southern Europe. (Karsten Eig)The Laurissilva forest is green not primarily as a result of rainfall, as the dry semi-deserts on the Canary Islands can testify. Instead, it catches the moisture which is carried to the island with the trade winds, which eternally blow from the humid north, touch the Canaries and then cross the Atlantic towards the Caribbean. In the morning, the mountains on the northern side of Gomera are often covered in fog – more reminiscent of a mystic place where hobbits could appear than a subtropical island.

The fog condenses on the trees, and drips to the ground, where the porous volcanic rocks deep below the island act as a large sponge and store the water. This water is the source for all the streams on La Gomera, and also supplies the drinking water. The precious forest is protected by the Garajonay National Park, named after the highest peak on Gomera. At 1,480m, Alto de Garajonay is easily reached by a short walk from the main road and offers a great view of much of the island. In the distance, the mighty Teide on Tenerife rises so high that one still has to look upwards towards the peak. Laurissilva forests also cover parts of La Palma, Tenerife, and some spots on Gran Canaria, always on the northern side of each island and at high altitude, facing the trade winds. As on Gomera, the southern side of the islands are protected from the trade winds, and are therefore half deserts, populated by cacti and lizards. Lanzarote and Fuerteventura are too low and to the east of the winds, and are therefore effectively deserts.

Volcano-shaped Island

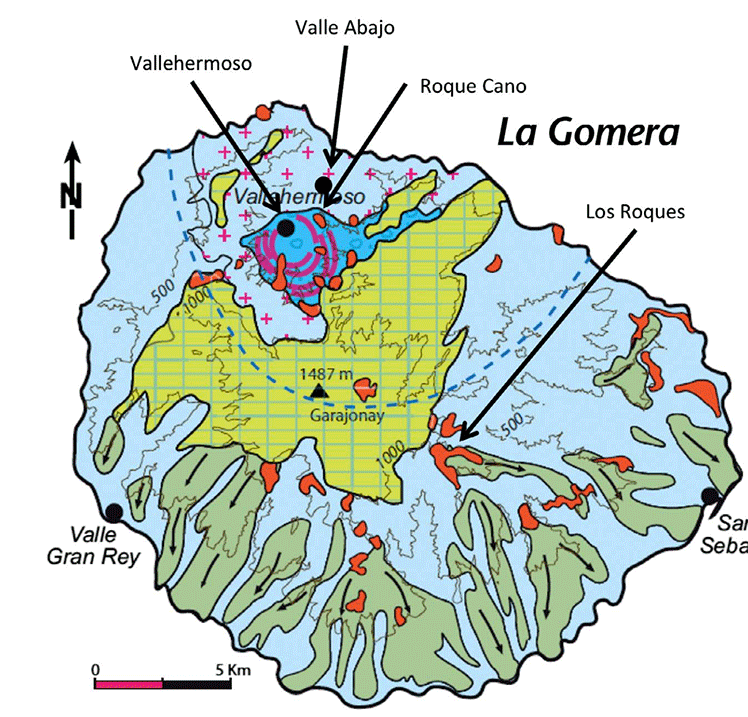

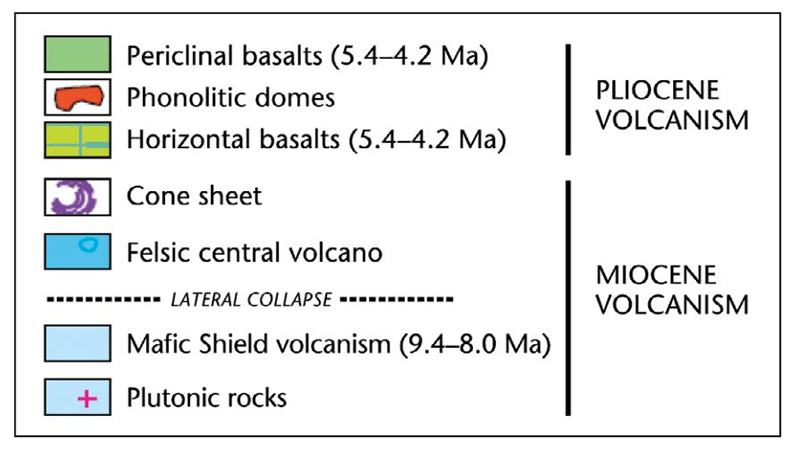

Now, let us look at the most interesting part for readers of GEO ExPro: the geology. From the map, one can easily recognise Gomera’s characteristic outline. The island looks like a giant fruit squeezer, with steep valleys radiating from the centre. Reminiscent of the shape of a volcano, with a peak in the middle, this form does not, however, reflect the original shape of Gomera. Volcanism originally took place in the northern part of the island, where a basal complex with abundant volcanoclastics, conglomerates and intrusives is exposed. If you walk the footpath from Valle Abajo, north of Vallehermoso, up the steep valley side, you can admire the complex intrusive-extrusive relationships, and the kilometre-long dykes which cross the valleys.

After Hoernle and CarracedoZeolites, which form where volcanic rocks and ash layers react with alkaline groundwater, are commonly found in the older volcanics. The vesicles are usually small, with analcime and hairy zaolites as the most commonly found minerals. If you pick up the rocks, be careful not to hurt the many lizards and geckos that hide in open fractures in the rocks.

After Hoernle and CarracedoZeolites, which form where volcanic rocks and ash layers react with alkaline groundwater, are commonly found in the older volcanics. The vesicles are usually small, with analcime and hairy zaolites as the most commonly found minerals. If you pick up the rocks, be careful not to hurt the many lizards and geckos that hide in open fractures in the rocks.

Gomera rose above sea surface approximately 20 ma, at which time volcanism moved to the centre, covering the island in plateau basalts with interbedded tuffs. These basalts, often developed as columns, as well as red tuffs, are beautifully exposed in cliffs on the south-west coast, near Valle Gran Rey. The many cycles of eruptions can be seen by the interchanging of lavas and red and orange tuffs. To the north of Playa del Ingles in Valle Gran Rey (with real, black volcanic sand!), a large fault has developed a characteristic half graben filled with tuff.

Gomera rose above sea surface approximately 20 ma, at which time volcanism moved to the centre, covering the island in plateau basalts with interbedded tuffs. These basalts, often developed as columns, as well as red tuffs, are beautifully exposed in cliffs on the south-west coast, near Valle Gran Rey. The many cycles of eruptions can be seen by the interchanging of lavas and red and orange tuffs. To the north of Playa del Ingles in Valle Gran Rey (with real, black volcanic sand!), a large fault has developed a characteristic half graben filled with tuff.

Rocas – Volcanic Plugs

For the last five million years, Gomera has been in the post-volcanic erosion stage, which has dug out the present shape with steep valleys spreading out towards the coast. Before roads were built, these steep valleys isolated communities, and the people of Gomera developed a unique means of communication – a whistling language which combines various frequencies, and uses increasing or decreasing tone as substitutes for letters.

Exposures of interbedded tuffs and basalts along the south-west coast of Gomera. (Karsten Eig)Due to erosion, today the ‘rocas’ which can be seen protruding into the landscape are now the main topographic evidence of volcanoes. These are steep-sided volcanic plugs, left behind when the surrounding, softer rock has been eroded, and they stand out as huge, thick obelisks above the landscape. Notable examples are the Roque Cano, standing guard in the hillside above the town of Vallehermoso on the north coast, and the four rocas at La Zarcita, which create a landscape from a science fiction movie – or to the more imaginative, as if four large trolls had been surprised by the sun and frozen to stone.

Exposures of interbedded tuffs and basalts along the south-west coast of Gomera. (Karsten Eig)Due to erosion, today the ‘rocas’ which can be seen protruding into the landscape are now the main topographic evidence of volcanoes. These are steep-sided volcanic plugs, left behind when the surrounding, softer rock has been eroded, and they stand out as huge, thick obelisks above the landscape. Notable examples are the Roque Cano, standing guard in the hillside above the town of Vallehermoso on the north coast, and the four rocas at La Zarcita, which create a landscape from a science fiction movie – or to the more imaginative, as if four large trolls had been surprised by the sun and frozen to stone.