The questions of ‘Why Ukraine?’ and ‘Why now?’ have been much discussed over the last few months. The world has watched with shock and some disbelief as November’s peaceful demonstrations in Kiev’s Maidan square have slid uncontrollably into a formal Russian annexation of Crimea and a build-up of Russian troops on Ukraine’s eastern border. The Ukrainian army has been attempting to clear Russian-speaking paramilitaries who have taken control of key buildings in eastern cities.

Ukraine has become the epicentre of a new cold – and possibly hot – war.

The role of energy – both Ukraine’s reliance on Russia and its position as a conduit to the West – is critical among the causes of the crisis, although energy dependency has also helped dampen any East or West impulse for escalation. Just as Ukraine and Europe are reliant on Russian gas, Russia is reliant on revenues.

The immediate question is how to avoid a civil war with both East and West being drawn in. An integral issue is how to resolve Ukraine’s gas debt to Russia, ensure continued supplies and avoid a sovereign default. Increasing the diversity of energy sources appears to be part of the long-term answer. Ukraine has both oil and shale gas potential, and could possibly import LNG and reverse the flows of its westward pipelines. Could these options provide some economic stability?

Why Ukraine?

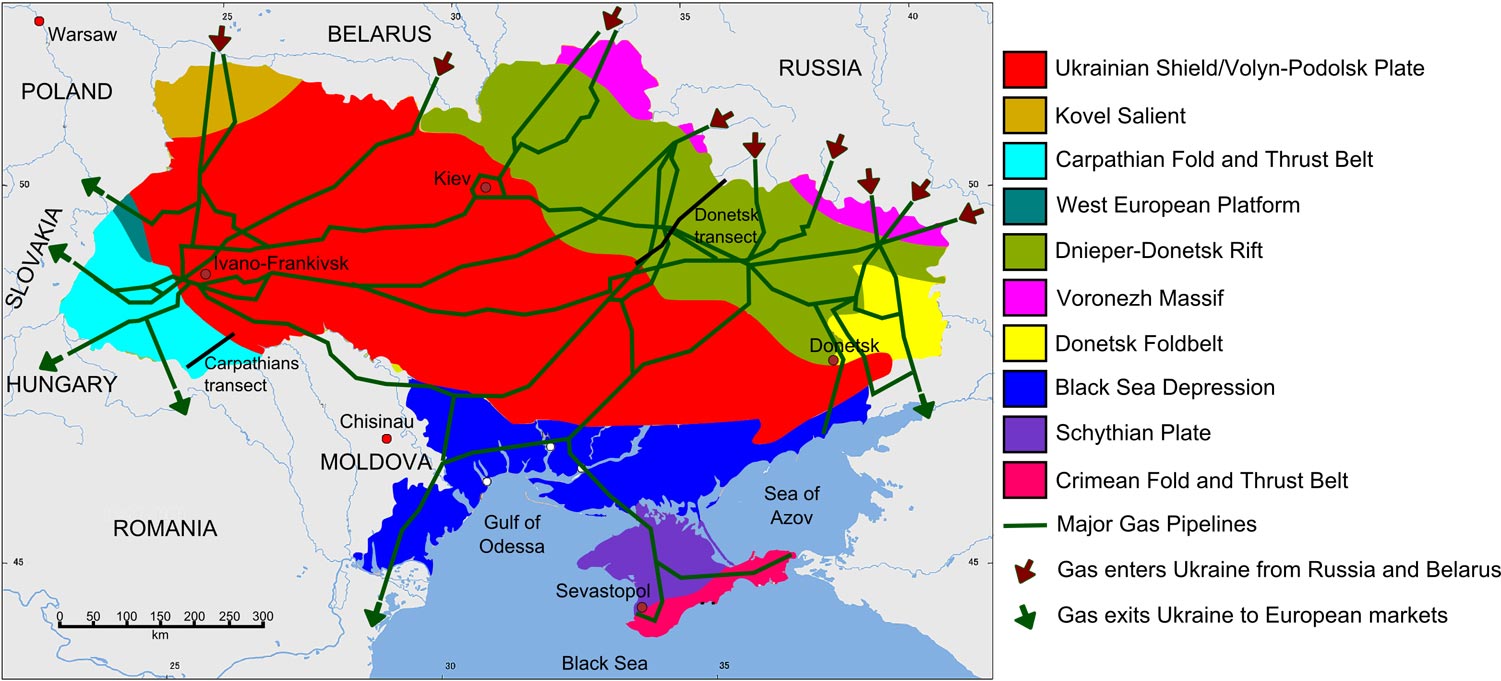

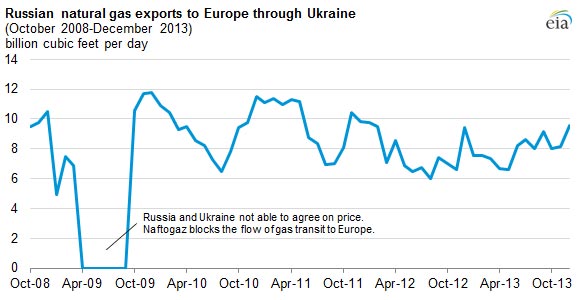

Russian natural gas exports to Europe through Ukraine (Bcfd). Source: EIA.Geo-politics and issues of national identity are central to the crisis: Russians consider the massive, central, former soviet republic to be a natural part of their territory, and moves by NATO and the European Union to draw Ukraine into their folds have been viewed with great hostility. Ukraine is crucial to Russia’s economy as, not only is it Russia’s single biggest foreign purchaser of gas, but it is the transit route for five major east-west pipelines. These provide a conduit for more than half of Russia’s gas exports to Western Europe and significant amounts of Russian and Kazakhstani oil.

Russian natural gas exports to Europe through Ukraine (Bcfd). Source: EIA.Geo-politics and issues of national identity are central to the crisis: Russians consider the massive, central, former soviet republic to be a natural part of their territory, and moves by NATO and the European Union to draw Ukraine into their folds have been viewed with great hostility. Ukraine is crucial to Russia’s economy as, not only is it Russia’s single biggest foreign purchaser of gas, but it is the transit route for five major east-west pipelines. These provide a conduit for more than half of Russia’s gas exports to Western Europe and significant amounts of Russian and Kazakhstani oil.

Why Now?

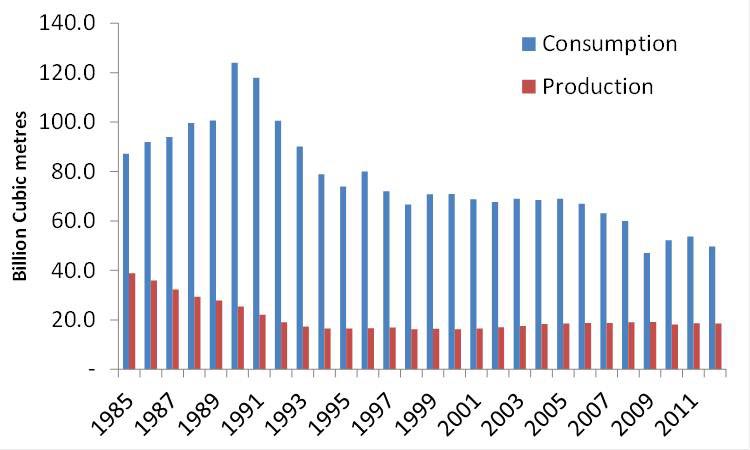

Ukraine: production versus consumption (Bcm). Courtesy of Nordea.Ukraine has been facing economic collapse for several years. Corruption has been the main problem, with a tier of Ukrainian oligarchs controlling more than a fifth of gross national product. Energy has been a major source of funds as ‘gas smuggling’ and profiteering from subsidised household fuel have been common. Energy also contributes to the structural deficit. Over 60% of national gas consumption is imported from the east and the price paid has been well over $400 per thousand cubic metres, a rate far higher than that paid by Western European countries and considered discriminatory by Ukrainians.

Ukraine: production versus consumption (Bcm). Courtesy of Nordea.Ukraine has been facing economic collapse for several years. Corruption has been the main problem, with a tier of Ukrainian oligarchs controlling more than a fifth of gross national product. Energy has been a major source of funds as ‘gas smuggling’ and profiteering from subsidised household fuel have been common. Energy also contributes to the structural deficit. Over 60% of national gas consumption is imported from the east and the price paid has been well over $400 per thousand cubic metres, a rate far higher than that paid by Western European countries and considered discriminatory by Ukrainians.

Gas contracts have been on take-or-pay terms. These are standard in the trade but Ukraine drastically cut its consumption after the 2008 financial crisis and claims it gave Gazprom adequate notice of the need to reduce imports. Gazprom rejects this and in January 2013 Kiev was faced with a $7 billion bill for not having imported the agreed amount in 2012, a sum equivalent to approximately 4% of GDP. Perhaps significantly, the bill arrived just hours before a landmark deal was signed with Shell at Davos giving the company exploration rights to Ukraine’s shale resources, and adding to the perception that Russia is using gas to control its neighbour.

Ukraine’s economic weakness has been exacerbated further by Russia cutting off its gas supplies in the winters of 2006 and 2009. The 20-day dispute of 2009 came at a particularly critical time as the economy slowed down after the 2008 global financial crisis.

Although it was the failure of Ukraine’s politicians to sign EU ‘political association’ agreements that sparked the Maidan demonstrations in November 2013, this has been complicated by the severe economic crisis and the need to choose between two rival, mutually exclusive bailout packages – an IMF or a Russian deal. In both, energy has been a significant factor.

Former President of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych, who was ousted in February after major street protests in Kiev. Source Igor Kruglenko.The IMF deal comes with standard conditions of freeing up the currency (in practice, a massive devaluation) and removing all state subsidies, particularly for fuel. These conditions are deeply unpopular in a country where the average wage is just $400 per month and winter temperatures can be as low as -20°C. Failure to remove fuel subsidies halted a previous IMF $15.4 bn assistance programme begun in 2010.

Former President of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych, who was ousted in February after major street protests in Kiev. Source Igor Kruglenko.The IMF deal comes with standard conditions of freeing up the currency (in practice, a massive devaluation) and removing all state subsidies, particularly for fuel. These conditions are deeply unpopular in a country where the average wage is just $400 per month and winter temperatures can be as low as -20°C. Failure to remove fuel subsidies halted a previous IMF $15.4 bn assistance programme begun in 2010.

The alternative on offer was a Russian bailout of $15 bn, the first $2 bn of which was given at the beginning of the crisis and is now being claimed back by Moscow. The ‘strings’ to this deal were a commitment to a customs union with Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia (seen as a nascent eastern counterweight to the EU), Russian control of the gas export pipelines that cross Ukraine and a withdrawal from the European Energy Community. The carrot was a gas price cut to $268.50 per thousand cubic metres, plus a loan to cover the debt to Gazprom.

The protests were sparked by President Yanukovich moving in favour of the Moscow deal, thereby closing off the option of closer integration with the EU. The eventual rejection of that deal means the country now faces the crippling price of $485 per thousand cubic metres, plus an $11 bn bill for arrears, amounts that have led Ukraine and the West to claim that Russia is using gas prices to make the country ungovernable.

Options

Alongside the IMF’s renewed bailout offer, it is being argued that Ukraine needs to rapidly diversify its fuel supplies and become more self-reliant. Energy conservation is the only immediate and effective option: since the IMF is insisting on a 50% increase in household prices from May 1, it is likely that consumption will drop, although the economy’s reliance on heavy industry will limit the effect.

In fact more than half of Ukraine’s energy comes from its own uranium and coal supplies (approximately 18% and 28% of electricity respectively). But the economy remains reliant on gas for 40% of its energy.

As with most of the central and east European countries, liquefied natural gas (LNG) is seen as the most obvious alternative and Ukraine is already constructing an import regasification terminal. Optimists hope that a north south supply corridor will be created to rival Russia’s east-west axis, and gas interconnectors are being improved.

Only the US is in any sort of position to increase exports in the foreseeable future and one Republican congressman has proposed an ‘Expedited LNG for American Allies’ bill. The aim is clearly not just to strengthen the bargaining power of European utilities but also to free up the West with regard to a more aggressive – possibly military – response should there be further annexations of territory.

However, the building of expensive liquefication and regasification terminals takes years and offers no immediate solution. Nor, given the costs involved, is American LNG likely to be cheaper than the gas on offer from Russia.

Greater Self-Reliance

It is unclear at present whether Ukraine’s shale reserves, believed to be the third or fourth largest in Europe, are commercially exploitable. The EU has, in January this year, issued guidelines that effectively ensure that environmental concerns do not prove an obstacle. However, companies will be mindful of the Polish experience where, despite large reserves, most major companies have chosen to quit, citing geological complications.

Ukraine’s oil consumption is a relatively modest 0.32 MMbopd (compared to the UK’s 1.5 MMbopd) and, before the annexation of Crimea, Ukraine’s Chornomornaftogaz, which pumped both oil and gas, had a small off-shore production of 80,400 bopd. However, the company has now been nationalised by the Russians, and Ukraine will now not benefit from recently negotiated Black Sea exploration deals.

With regard to Ukraine’s $3 bn a year earnings as an oil and gas conduit to the West, this source of income was already being undermined by new pipeline projects: in 2009 Nord Stream became operational, bringing gas direct to Europe via the Baltic Sea, avoiding eastern Europe altogether, and a South Stream project under the Black Sea is waiting EU approval. Its construction, though some way off, will ensure that all Western European demand (30% of its total gas consumption) could be met without the need to transit Ukraine at all (Ukraine is currently the transit route for 16% of all European gas requirements).

The possibility of actually reversing the flow of the pipeline through Slovakia is an option for reducing Ukraine’s dependence on Russia. However, Ukraine is likely to continue to derive income from the massive Druzhba oil pipeline, one of the biggest networks in the world.

Prospects

Arseniy Yatseniuk, Interim Prime Minister of Ukraine. Source Arsen Yakovenko.Ukraine’s interim Prime Minister Yatseniuk says he is willing to pay the current $2.2 bn billion bill, but objects to the extremely high price of $485 per thousand cubic metres and the repayment of past discounts. Russia is, reportedly, insisting that gas is now paid for in advance. Supply cuts may be prevented only by the fact that Russia is wary of the escalation this would bring, the risk of pushing the West into a more rapid diversification of supply, and exacerbation of Europe’s investigations into Gazprom’s abuse of monopoly power.

Arseniy Yatseniuk, Interim Prime Minister of Ukraine. Source Arsen Yakovenko.Ukraine’s interim Prime Minister Yatseniuk says he is willing to pay the current $2.2 bn billion bill, but objects to the extremely high price of $485 per thousand cubic metres and the repayment of past discounts. Russia is, reportedly, insisting that gas is now paid for in advance. Supply cuts may be prevented only by the fact that Russia is wary of the escalation this would bring, the risk of pushing the West into a more rapid diversification of supply, and exacerbation of Europe’s investigations into Gazprom’s abuse of monopoly power.

With regard to a bailout, decisions are complicated by the fact that, till elections in May, the West is dealing with an interim government. Unpopular austerity measures – particularly the rapid removal of fuel subsidies – may produce the ‘wrong’ election result and drive much of the population towards Russia.

Anti-corruption measures are to the fore, with the hope that Ukraine can emulate Georgia in curbing the problem. Appeals have been made to Ukraine’s oligarchs to repatriate their funds and provide their own bailout.

The immediate focus is on the possibility of civil war. If this can be avoided, economic stability will be the primary goal and for this, less dependence on Russian gas seems essential. Few options will deliver the necessary results within the next year. The best hope is that East and West co-dependence on gas and revenues will allow a negotiated compromise.

References/Further Reading:

- EIA: Ukraine Country Data

- GeoExPro v11i1. Premature Predictions for LNG? Nikki Jones

- GeoExPro iPad Ed9. Russian Oil and Gas: No Guarantees on Growth. Nikki Jones

- Hydrocarbons Technology. LNG terminal in Ukraine.

- Oszczypko, N., et al, 2006. ‘Carpathian Foredeep Basin (Poland and Ukraine): Its Sedimentary, Structural, and Geodynamic Evolution’, in J. Golonka and F. J. Picha, eds., The Carpathians and their foreland: Geology and hydrocarbon resources: AAPG Memoir 84, p. 293 – 350.

- Reuters – ‘Ukraine signs oil, gas deal with Eni and EDF, sees $4 billion investment’

- Tari, G and Wagner, K (Chief Editor) ‘Ukraine. Exploration Country Focus.’, AAPG.

- Ukrnafta website – History

- Ulmishek, F. G. 2001. Petroleum Geology and Resources of the Dnieper- Donets Basin, Ukraine and Russia. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2201-E