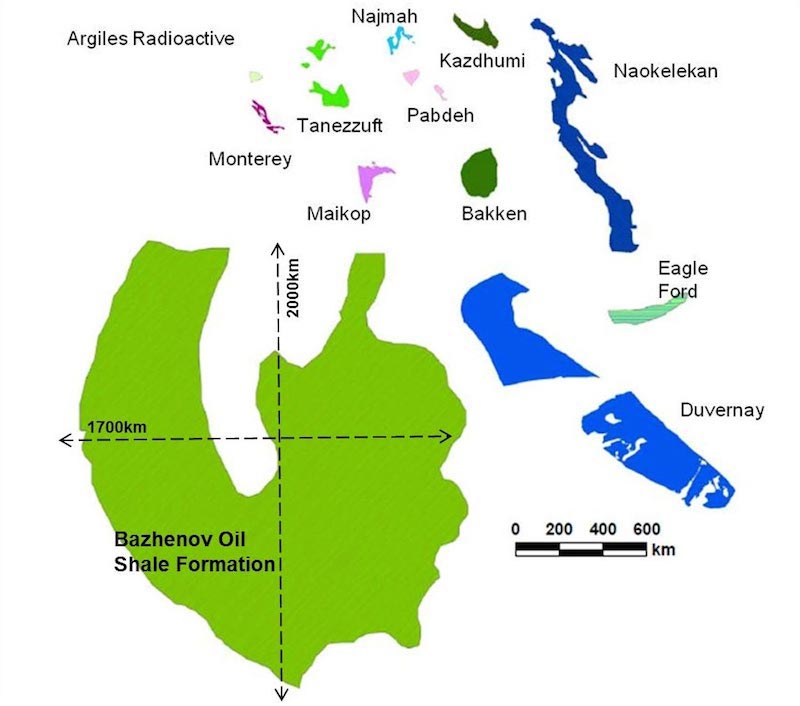

In 2013 Russia has come to equal Saudi Arabia in oil production, reaching a post-Soviet high of 10.4 MMbopd: in terms of total hydrocarbons, the figure is an impressive 21 MMboepd. The country accounts for almost 13% of the world’s oil supply, and there is clear further potential in its massive shale reserves and the Arctic, both of which are only just starting to be explored and developed. The Bazhenov Formation in western Siberia is vast, dwarfing the North American shale fields of Bakken, Eagle Ford and Duvernay, while the Russian Kara Sea alone holds the tantalising possibility of 100 Bboe. It would appear that there is much to be hoped for from Russia in terms of long-term supply and price stability.

False Impressions

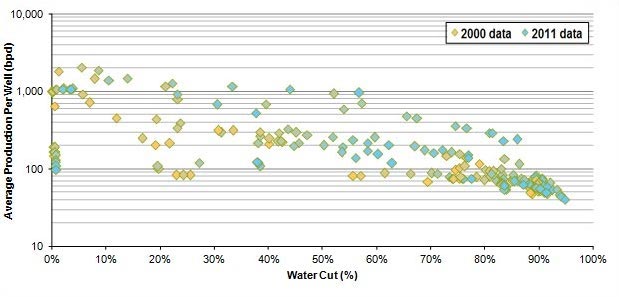

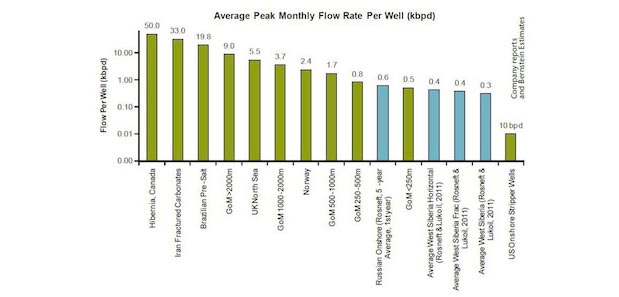

However, many observers argue that these headline figures are misleading and that production will begin to slip as early as 2015. According to Oswald Clint, Senior Analyst at Bernstein Research, Russia is having to run fast just to stay still, relying on ageing fields with declining output. Russian oil now comes mainly from Soviet-era fields, with new fields contributing approximately only 12%. Typically, older wells are now producing only 50–70 bpd, with a water cut of over 90%. In consequence, these fields are being worked hard and companies are drilling many more wells in order to maintain production levels. According to analysis by Bernstein Research, Lukoil now has to drill thousands of wells to achieve a volume equal to just 80 or 90 wells in the Gulf of Mexico.

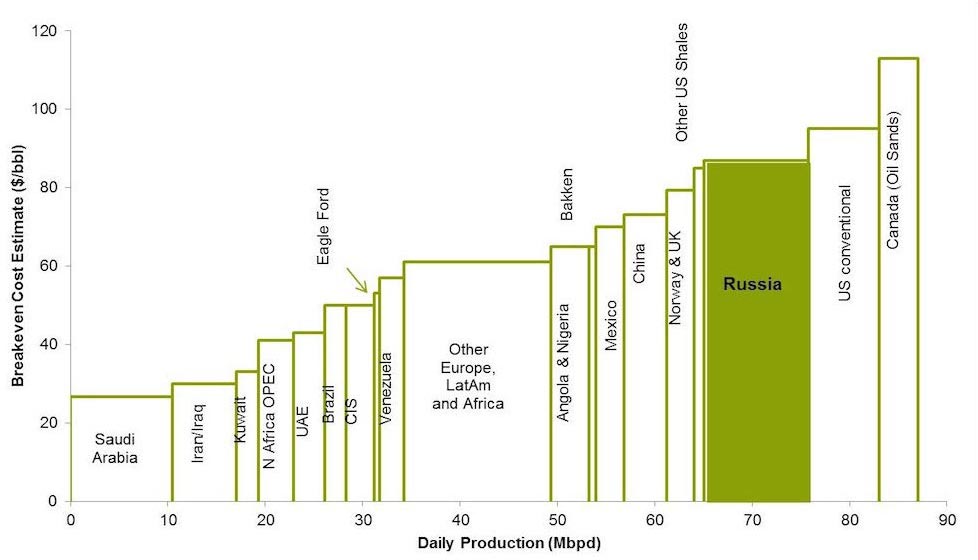

The cost curve has risen dramatically. Companies now need a price of $90/bo simply to make a 10% return. However, this is not just the cost of physical production, which remains relatively low at approximately $3 per barrel. Long-distance transport adds a further $8/bo and other factors bring the physical cost of getting oil to market close to $20/bo. The largest additional cost is the export duties, currently over $50/bo. Together these factors place Russia’s marginal rate of supply below only US conventional production and Canadian oil sands, but above those of every other region, including Nigeria, Venezuela, the North Sea and US shale.

It is not just the tax rates that make Russia a less-than-attractive investment opportunity. Onshore fields typically have a longer ramp-up period than fields in the North Sea and elsewhere: Russian fields typically take 40–50 years to reach peak production compared to just two to three years in other parts of the world. Despite this, it is high levels of capital expenditure that are currently supporting Russian production: according to Oswald Clint, CAPEX is now approximately $6 per barrel compared to just $2 six or seven years ago. All costs are rising.

Little Appetite for Exploration

Because of a combination of tax and political factors there has been little appetite for exploration, although this may be changing. Legal restrictions apply to all ‘strategic deposits’, i.e. those of more than 500 MMbo or 1.77 Tcfg, which are reserved for the state backed companies. But foreign companies are moving in and hundreds of smaller blocks are being auctioned monthly in a fairly transparent manner, despite the major disincentive that bidding companies risk not being given a production licence if they make a significant find. As Julian Lee, Senior Energy Analyst at the Centre for Global Energy Studies, points out, often there are no bids for blocks – apart from the licensing risk, companies face a high level of bureaucracy, limited geological and geophysical information and the prospect of working in very challenging terrain with poor transport infrastructure.

New technology may bring some hope but, according to Clint, much of the ‘low hanging fruit’ in terms of enhanced recovery has already been picked. There is a potential two trillion barrels of oil in the 2,300,000 km² of shale formation and currently the Russians are only using conventional seismic technology to identify suitable natural fractures for drilling, which leaves the potential for further recovery through US-style fracking. However, the inhospitable environment, the need for expensive site clearance, and the lack of infrastructure all add to the cost of development in this area. In terms of environmental costs, as yet the Russian people appear relatively unconcerned but it is possible that international pressure may become a factor as climate change calculations add in the high levels of methane that are being released.

The areal extent of the Russian Bazhenov Oil Shale Formation dwarfs that of high producing US areas. Source: Neftex, Company Reports, Bernstein AnalysisSimilarly the Arctic, for all its promise, comes with great costs and high risks. Despite the polar cap’s melting, there is still only a limited drilling window of a few summer months. Apart from the possibility of spills, for which the Arctic Council has been attempting to agree a treaty this year, the current rush for the Arctic has the potential to become a military engagement. The 1982 Law of the Sea gives each state an Exclusive Economic Zone of 200 nautical miles for fishing and fossil fuels but lack of international law beyond this point led Russia to plant its flag in the North Pole seabed in 2007. Both Russia and Norway have made submissions to extend their EEZs on the basis of their continental shelves: Norway’s bid has been accepted but Russia has been told to come back with better data. Canada and Denmark are likely to submit soon with bids that may overlap Russia’s. It has

The areal extent of the Russian Bazhenov Oil Shale Formation dwarfs that of high producing US areas. Source: Neftex, Company Reports, Bernstein AnalysisSimilarly the Arctic, for all its promise, comes with great costs and high risks. Despite the polar cap’s melting, there is still only a limited drilling window of a few summer months. Apart from the possibility of spills, for which the Arctic Council has been attempting to agree a treaty this year, the current rush for the Arctic has the potential to become a military engagement. The 1982 Law of the Sea gives each state an Exclusive Economic Zone of 200 nautical miles for fishing and fossil fuels but lack of international law beyond this point led Russia to plant its flag in the North Pole seabed in 2007. Both Russia and Norway have made submissions to extend their EEZs on the basis of their continental shelves: Norway’s bid has been accepted but Russia has been told to come back with better data. Canada and Denmark are likely to submit soon with bids that may overlap Russia’s. It has

been noted that Russia is building up its military capability in the area, and other states have made similar moves.

Oil Price is Critical

The price of oil is critical if investment is to continue. As many observers have noted, technology is not only not bringing the cost of production down but it is increasing supply, which brings the threat of weaker prices. There appears to be little room for cost reduction although the government has said it will waive some taxation in order to encourage investment in shale. However, it is likely to remain reluctant to significantly reduce its fiscal take since its sovereign wealth funds are weak compared to other oil-producing states or China. However, interestingly – and possibly inadvertently – Russia has been supporting a high Brent price this year by exporting less to Europe, refining and consuming more at home and rapidly increasing its exports to China. This Asian pivot has been made possible with the new Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean pipeline and in June, Rosneft signed a deal to double shipments. Russian oil has, in the past, generally traded at a discount to Brent, reflecting its poorer quality, but this summer it has traded at a premium as European refineries have seen supplies cut. Russia’s reorientation towards the East is effectively pushing up the global benchmark and possibly making investment more secure.

Gas Investments Dubious

However, 50% of new Russian production is gas and Russia’s market – and international prices – have appeared less secure over recent years as America has developed its shale reserves and Europe has threatened to follow. Last year, Gazprom was forced to abandon the Shtokman gasfield in the Barents Sea when its US market dried up, and similarly Total and Statoil abandoned Snøvit: the two developments have thrown long shadows over all gas investment. However, the threat to prices is not simply from global over-supply but from LNG connecting hitherto disconnected producers and consumers and creating a global market. Russia – as keeper of 18% of world gas reserves – is threatened with the end of long-term bilateral contracts that have standard take-or-pay clauses and are indexed to oil. In 2012, Gazprom was forced to make significant concessions to customers, and the EU Commission began an anti-monopoly investigation of the company, forcing it to pay substantial amounts to European utility companies.

The research vessel Academik Mstislav Keldysh surveying the Russian Arctic Shtokman field in 2010. Last year, Gazprom was forced to abandon the field development when its US market dried up. Source: Shtokman Development AGHowever, as long as Japanese demand remains high in the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster (they are the main spot purchasers), and Europe remains tentative about developing its own shale, Gazprom appears secure in its investments. Last year, it increased its average daily production by 30,000 bpd and has attempted its own Asian pivot, although Putin remains fearful that gas will find its way back to Europe and undermine Gazprom’s market there.

Unexpectedly, a significant threat to Gazprom comes from Rosneft, the only Russian company that is truly performing well. Under the presidency of Igor Sechin, KGB veteran and confidant of President Putin, the company has taken over TNK, moved into the Gulf of Mexico, begun ‘tight oil’ production in Siberia and, since 2012, a drilling programme in Russia’s Kara Sea. In 2012 Rosneft replaced 130% of its reserves, and 200% each year between 2009 and 2011. Increasingly looking like a ‘supermajor’, Rosneft now produces 4 MMboepd, more than ExxonMobil. In July, Rosneft took control of Itera, an independent gas producer, signalling that it aims to move into the gas business in a significant way, and break Gazprom’s monopoly on gas exports. Exactly how that will work out in terms of Russian politics is unclear, as are the implications for future gas investments.