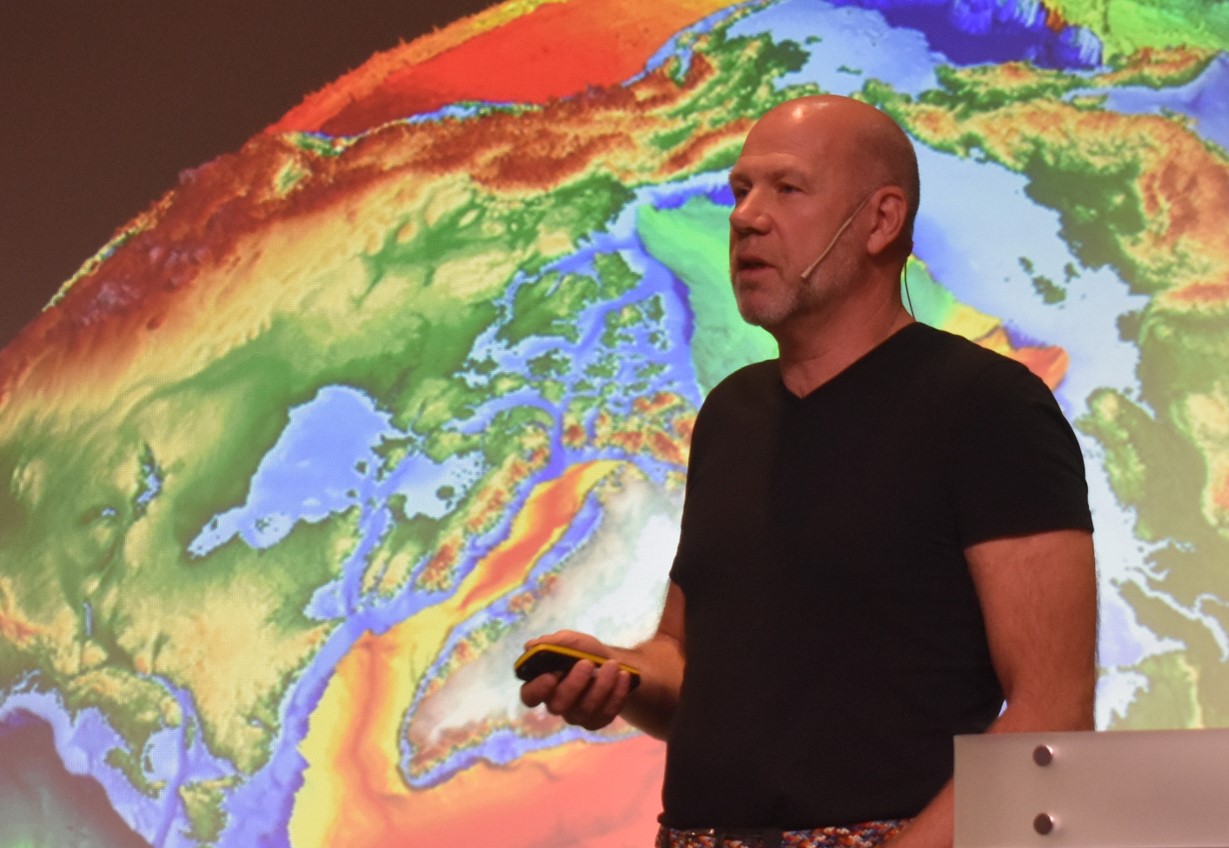

“All extractive activity comes with costs, both in terms of money and in terms of environmental impact. Many terrestrial mines have to blast and move huge amounts of waste rock to reach the ore. Ten percent of our CO2 emissions come from the extraction and crushing of rock,” said Ebbe Hartz, Lead Geologist at Aker BP during the GeoPublishing Deep Sea Minerals conference in Bergen last week.

Hartz pointed out that deep-sea minerals occur with far higher grades than the mineral deposits we find on land. That offers several advantages, including lower costs of extraction. It also means that we need a much smaller area to operate on per kg of metal we want to extract, the geologist claimed.

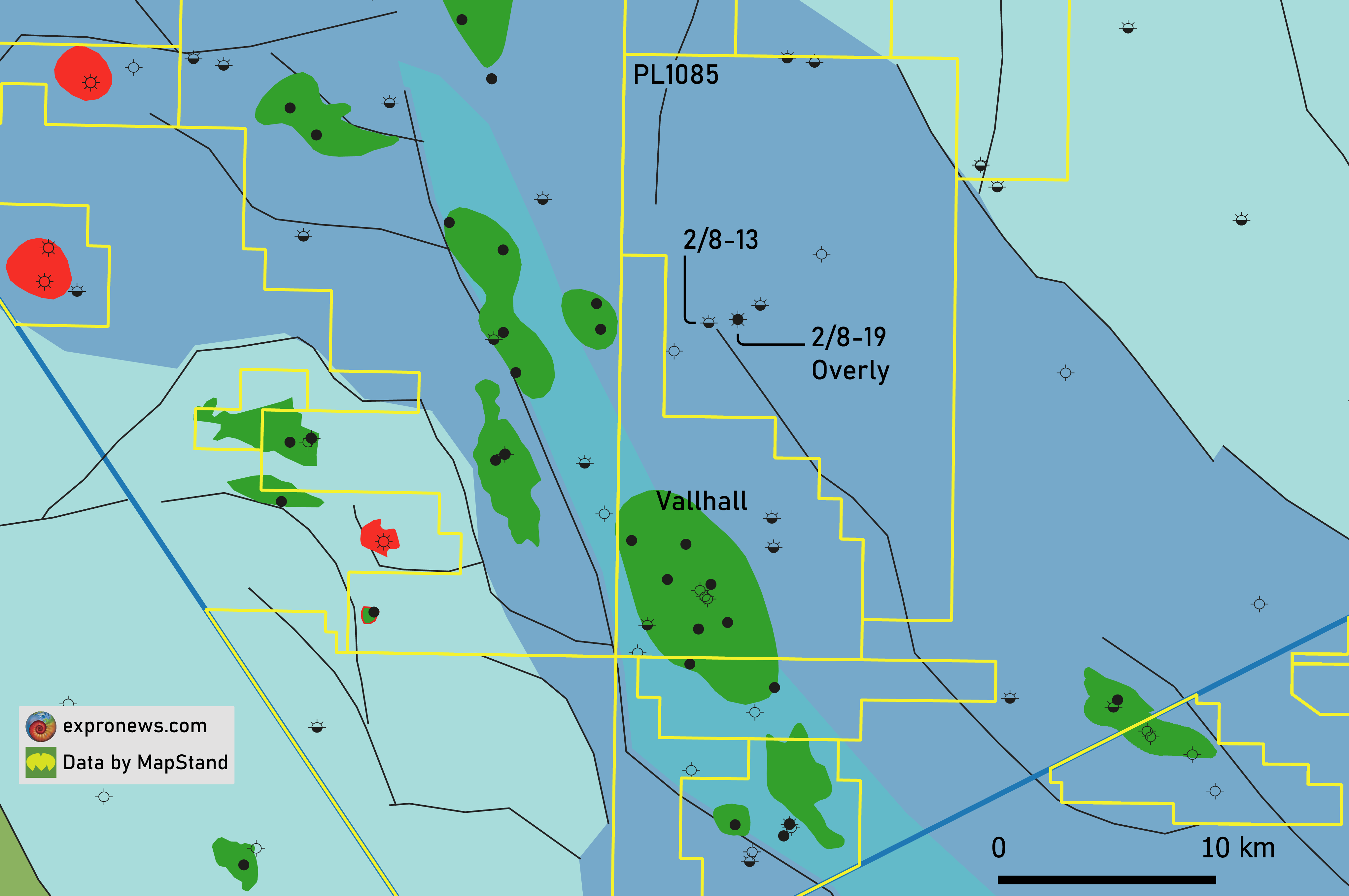

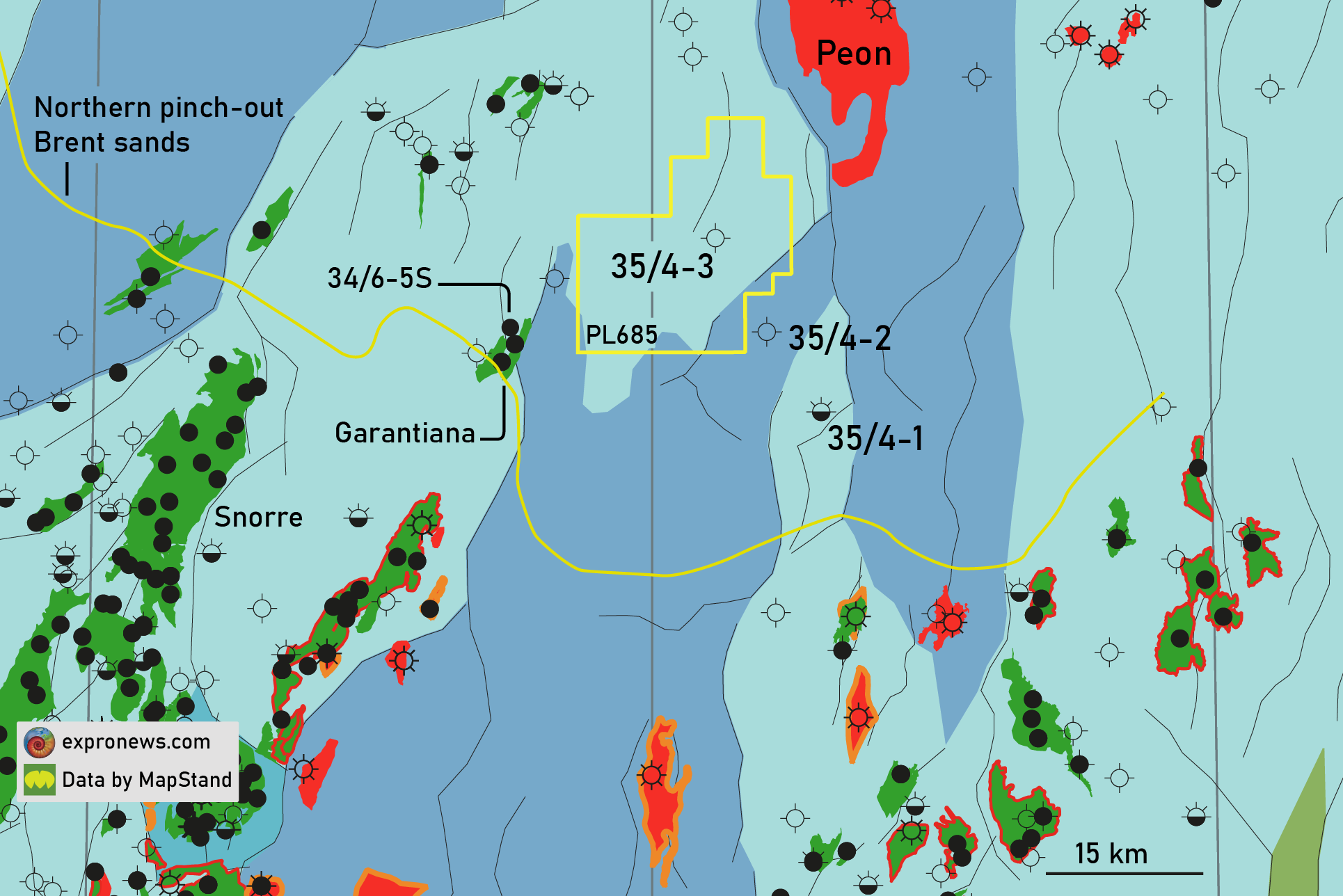

During his talk, he presented several diagrams that illustrate what this could mean for Norway. This country is potentially approaching the end of the opening process first set out by the former government in 2019. In the Norwegian exclusive economic zone, which includes the Atlantic spreading ridges, we find both seafloor massive sulphide (SMS) deposits and cobalt-rich crusts.

An FPSO for deep-sea mining

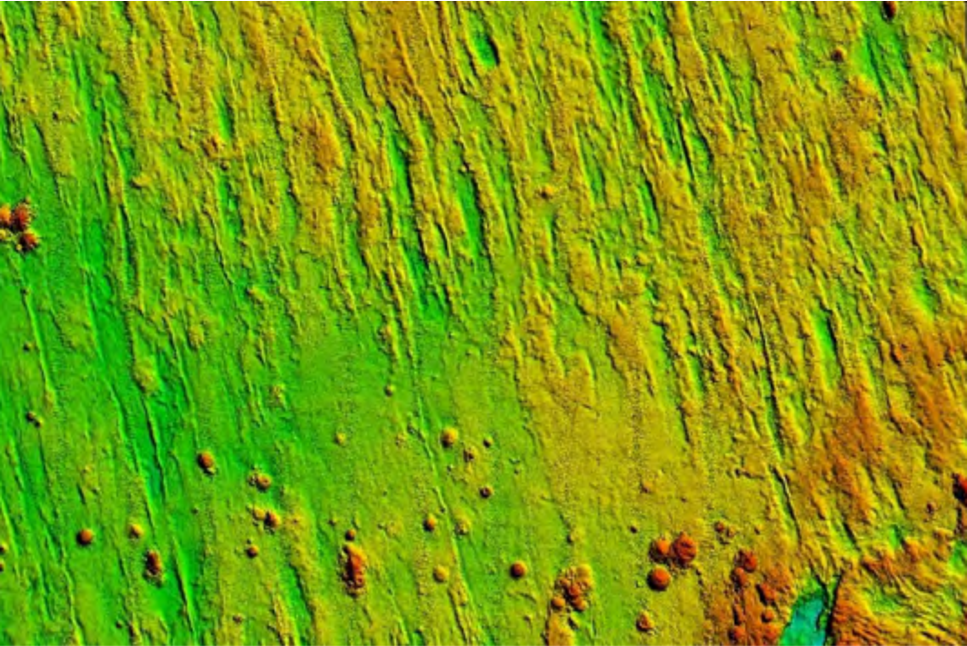

Aker BP’s calculations are based on the use of floating production, storage and offloading vessels (FPSO), which can turn round two million tonnes per year. “One mine on the seafloor, producing two million tonnes of ore per year, will occupy far less than one square kilometre. This is in stark contrast to many mines on land, which consume much larger areas,” says Hartz.

According to Hartz, a potential deep-sea mine at a sulphide deposit on the Mohn’s Ridge could make Norway more than self-sufficient for cobalt, copper, zinc, silver and gold. Of these metals, cobalt is the most important if we consider the EU’s definition of supply risk, while gold could contribute the highest value per tonne of ore.

Self-sufficient

For a Norwegian mining operation based on the extraction of crusts, Norway can be self-sufficient in as many as ten metals. “Of these metals, scandium will be the one we can export the highest share of; Norwegian scandium production based on a small mining operation (a quarter of a million tonnes per year) can cover almost the entire global demand,” Hartz mentioned.

Environmental concerns

The Aker BP geologist reiterated that mining operations in the deep sea have negative environmental consequences but maintained that many of these can be handled with the right choice of design and technology. He explained that the company spends a lot of resources on modelling plumes (sediment clouds) that are swirled up when activities take place on the seabed.

Another impact is noise, but the geologist claimed that this too is fully manageable, for example by placing the pump that will retrieve the material from the seabed on the production ship instead of in the water.

In conclusion, the geologist said that Norway has everything needed to start mineral extraction on the seabed, including an industry that cooperates well with the authorities, and that what remains is for the government to open a licence round for exploration. This could potentially happen next year, as the impact assessment in connection with the opening process was recently put forward for public consultation with deadline in January 2023.

Aker BP sees mining of deep-sea minerals as a profitable line of business, albeit not to the same extent as the oil and gas activities.

A very rare metal

Scandium was highlighted as an interesting metal for Norway during last year’s Deep Sea Minerals conference. Former USGS geologist James Hein said that the crusts in the deep sea in the Arctic Ocean and in the Norwegian economic zone are highly enriched in this metal, which makes the deposits economically interesting. According to Hein, the average content of scandium in Arctic crust is 48 grams per tonne, which is significantly higher than the content of crusts in other parts of the world’s oceans (geoforskning.no: A very rare metal).

Scandium belongs to the group of rare earth elements (REE). It is a light raw material that can be used together with aluminium to form lighter and stronger aluminium products that are more corrosion resistant and heat tolerant. This makes scandium-aluminium alloys interesting for aerospace and military applications. Scandium is also used for high-intensity lighting (“stadium lights”), high-voltage power transmission and in 3D printing. Other applications include television and fuel cells. According to scrapmonster.com, scandium with 99.99 percent purity has a kilo price of 341,000 US dollars. It is approx. six times the price of gold.