“The Netherlands will go ahead with plans to end gas production at the large Groningen field next year,” Reuters reported on the 24th of September.

Similarly, as written by S&P Global on the 16th of September, “The Dutch government would not reconsider any change to its policy on gas output from the giant Groningen field.”

True, in case of extreme weather conditions the field will be allowed to produce a limited amount, but that is it. Under the current plans, a minimum flow is expected to continue from the field of around 1.3 Bcm, but full closure is expected between 2025 and 2028.

A reminder

A reminder of the main reason to halt production from Groningen was presented only last week, when three minor earthquakes were recorded. Even when damage may be small or absent, there is no discussion as to what caused the ground to move: compaction caused by depletion of the Rotliegend reservoir at around 3000 m depth.

What can be done to compensate for the loss of production from the Groningen field? Only a few years ago, it still produced more than 50 Bcm in a year.

Fortunately, Norway is the third largest gas producer in the world and because it does not use much gas itself, it is able to even ramp up gas export to Europe as recently announced. However, this is only a modest increase, with the Oseberg field now allowed to produce 6 instead of 5 Bcm and Troll ramping up from 36 to 37 Bcm. That is not going to make a difference on a total European consumption of more than 400 Bcm a year.

At the same time, Europe is reluctant to increase dependency on Russia even further, and competition for LNG loads has only been increasing due to demand from the Far East.

Europe is between a rock and a hard place, with gas prices going through the roof recently. In addition, as we already reported on recently, gas storage facilities have only been partly filled, further exposing the supply system.

Back to Groningen

With all of that in mind, it should not be too surprising that some people are raising the possibility to reverse the decision to cease production from Groningen, as Cyril van Wildershoven argued in an opinion piece last week.

There is around 450 Bcm (2,833 MMboe) left in the field, which is not much compared to the 2,800 Bcm of initial reserves, but still an amount that can significant alleviate pressure on the European market for years to come.

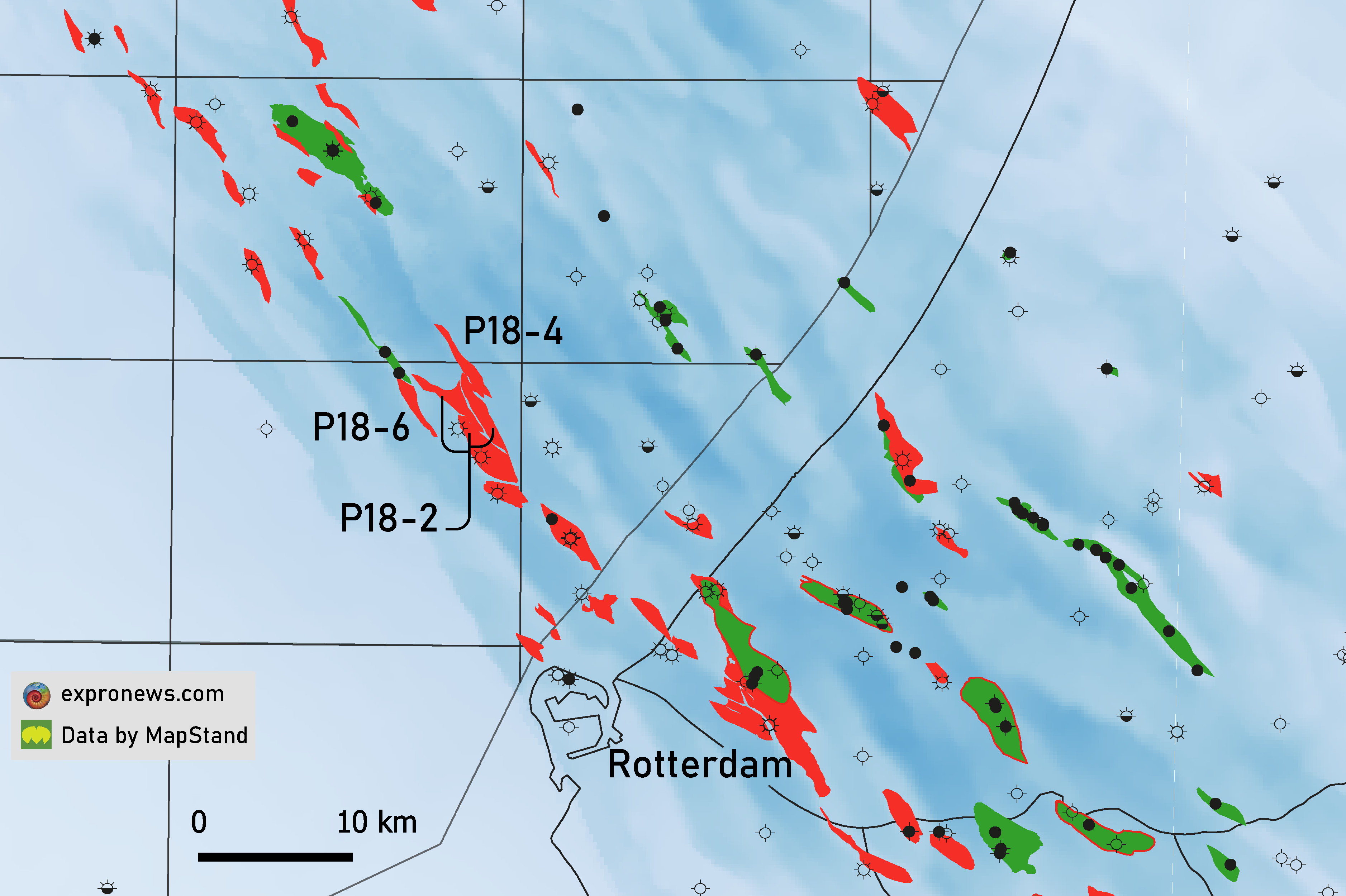

For obvious reasons, many people still argue that focus should be on maintaining production from smaller offshore gas fields in the Dutch sector rather than reassessing Groningen. However, it is a fact that production from most gas assets in the Dutch offshore has been declining rapidly over the past decades and only amounted to 13.3 Bcm last year, further dropping to around 5 Bcm in 2030. Small offshore fields are not going to make a big difference.

And although EBN estimates that there is around 30-50 Bcm expected to be discovered from the Dutch offshore area, it is clear that it is not a matter of just opening taps offshore – there are simply not the (proven) volumes.

On that basis, we have to accept increasing dependency on imports and Russia in particular, whilst reducing our dependency on fossil fuels in the years to come. At the same time, exploration drilling has to ramp up in order to add some volumes. Even though the Dutch government introduced a tax incentive for offshore explorers last year, the number of wells drilled is still very much depressed (only one exploration well was completed so far this year).

Against the backdrop of all these observations, it is not too much of a surprise that some people mention Groningen as an option to keep gas flowing. The coming winter months will show how precarious the situation will get.

HENK KOMBRINK