“Much of the seeming undisturbed landscape around us is anthropogenic in origin,” says Graham Leslie from the British Geological Survey when introducing a group of geologists to the area last weekend.

We are in the Midland Valley of Scotland, once the powerhouse of the country where Carboniferous coal was mined since and probably even before the Industrial Revolution.

The legacy of this mining activity finds a spectacular geological climax in the Spireslack abandoned open cast mine along the southern margin of the Midland Valley. Structural, stratigraphical and sedimentological aspects of the Carboniferous depositional systems come together to an extent that it forms a perfect training opportunity for those working in subsurface mapping in general and prospect generation in particular.

The mine exposes a cliff hundreds of metres long and tens of metres high where the rapid vertical changes in sedimentary environments can be inspected – from fluvial sandstones to overbank fines and swamps to shallow marine environments. Even better, lateral changes can be observed within the cliff face, which is such an essential aspect for any subsurface professional to be aware of when dealing with volume uncertainties.

An example of lateral facies change can be seen in the picture above, where a coarse-grained fluvial sand body of the Spireslack sandstone terminates abruptly against overbank fines where it eroded into. Another interesting observation that can be made is the more thinly-bedded sandstone at the top that does continue further towards the left. Does it represent the levee deposit of the main channel or is it a second phase of deposition? Regardless, it points out very well how fluvial systems have a limited lateral extent.

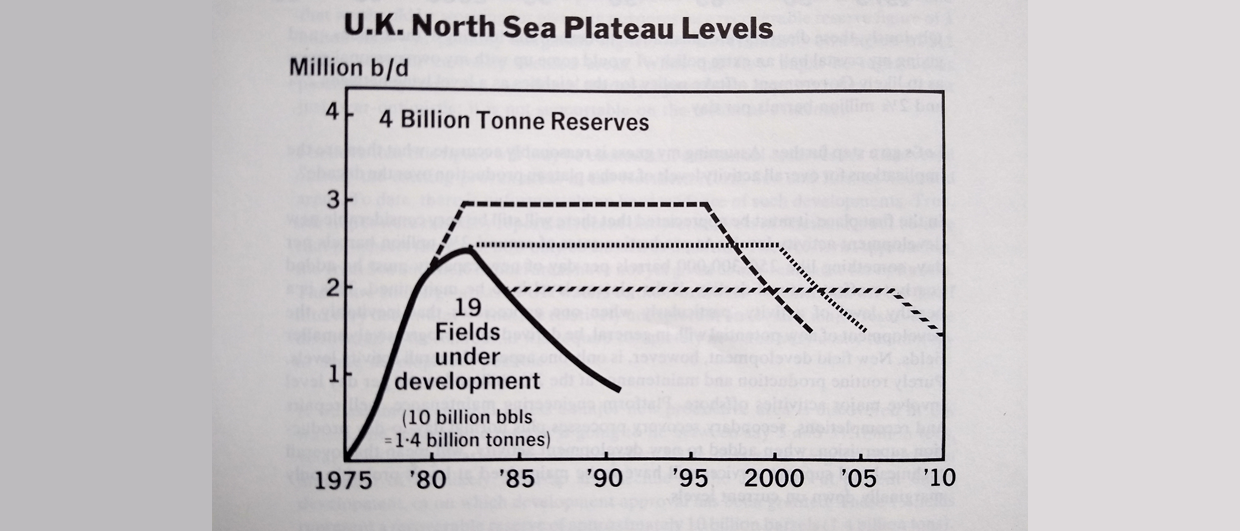

The size of the prize

It is the combination with structural features observed in the Spireslack mine that makes this location such a good example of subsurface evaluations. Situated in the updip limb of a NE-SW trending syncline, the faults and fractures that can be very well observed at the exposed dipslope form the keys to unravelling the structural history of the area.

Below is a picture of the dipslope, which shows a textbook example of a relay ramp. Offsetting the reservoir by only a metre or so, they are a reminder of the subseismic subsurface complexities when dealing with structurally complex settings – settings that are increasingly targeted in attempts to prove additional volumes in the mature basins of NW Europe.

As Graham Leslie explained, using a classic strain ellipse and superimposing it on the fault trends observed, a model of sinistral transpressive deformation is the most likely candidate to explain the different fault directions in the “compartment” exposed in the mine. The fascinating aspect about this observation is the way it can be subsequently used to put it into a much more regional perspective of the Midland Valley and even the continental configuration at the time. In that sense, a visit to site like this not only broadens ones view on sedimentological and structural geological aspects of reservoir-scale geology, but also the understanding of how observations relate to a much more regional picture.

On that basis, the Spireslack mine outcrops form an ideal playground for anyone wanting to do an exercise on the challenges of subsurface prospect evaluations, as it is essentially a small prospect being exposed here.

HENK KOMBRINK

For anyone interested in a field trip to the Spireslack abandoned mine complex, please get in touch through henk@geo365.no