As Bloomberg Energy expert Javier Blas showed on Twitter last week, both the UK and Dutch gas benchmarks closed at all-time highs. Combined with the fact that due to the cold spring many gas storage sites have not been filled to levels as expected – in the Netherlands, the degree to which the main gas storage sites have been filled sits at around 40% whilst it should be at 75% at this time of the year -, some experts argue that a cold winter could lead to gas supply problems.

Let’s have a look at gas storage capacities of the UK, Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway.

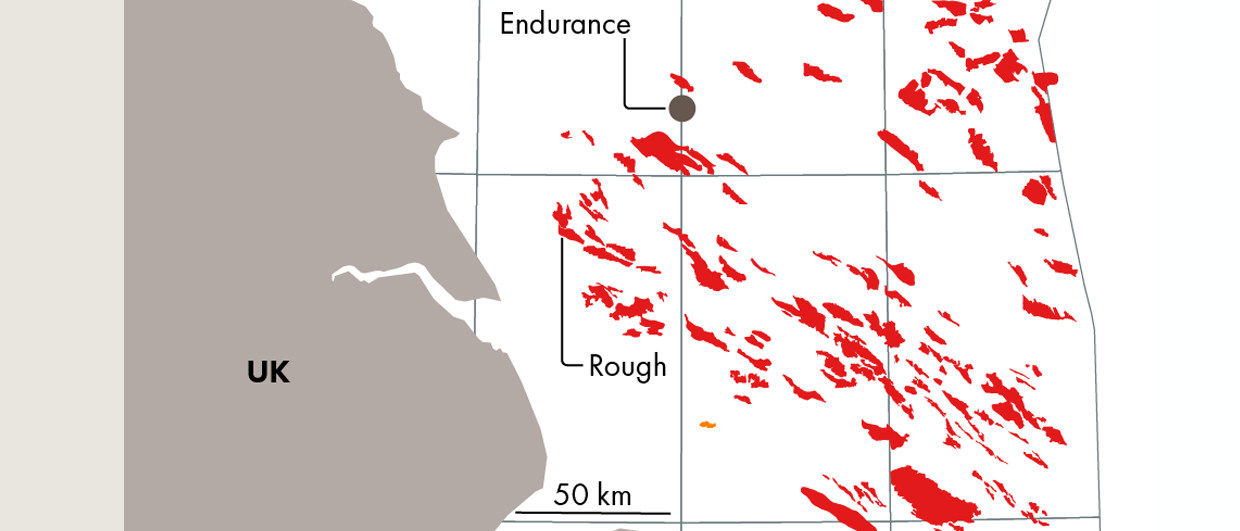

In the UK, an OFGEM 2018 document lists nine storage facilities in total, which could store up to 1.7 Bcm (10.7 MMboe) of gas in depleted gas fields and salt caverns. With an annual consumption of around 75 Bcm, it is clear that in case of a shortage of supply, the gas storage facilities, even when completely filled, would not last very long at all. It is also worth knowing that the UK produces around 45 Bcm of gas a year, leaving the country open to import-related fluctuations without storage facilities being able to compensate for a long time.

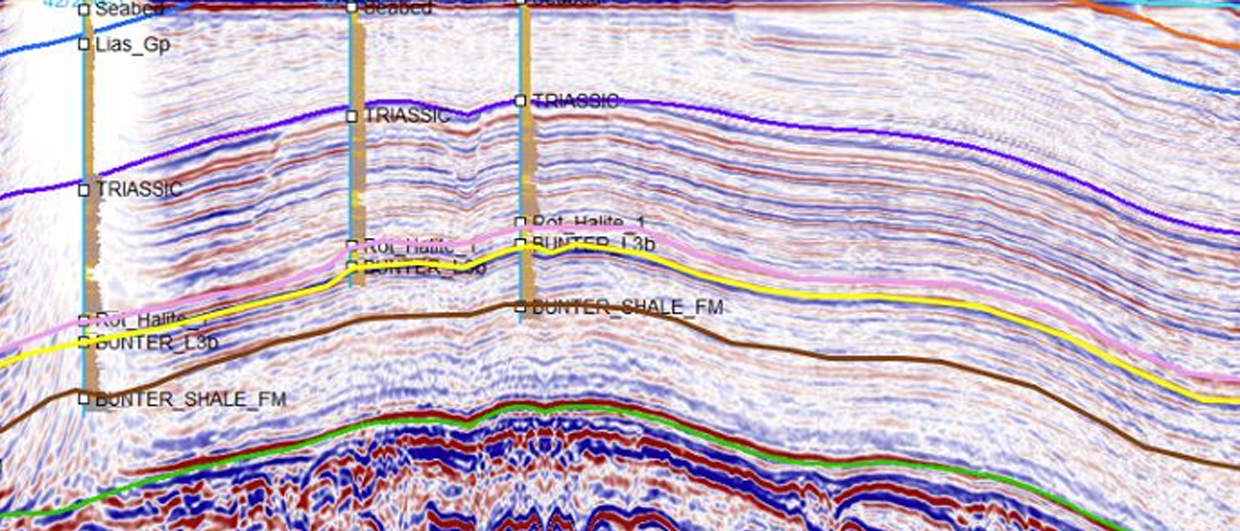

Larger than all of the above-mentioned gas storage facilities in the UK combined is the offshore Rough reservoir, which had a working capacity of 3.65 Bcm. However, operator Centrica ceased operating Rough in 2017, probably because of aging infrastructure. At the same time, plans have recently been unveiled to transform the Rough storage field into a hydrogen store, at a cost of approximately £1.6 billion.

In the Netherlands, five onshore storage facilities are in operation, with one in salt caverns and the rest in depleted gas fields. Together, they can handle a total volume of 12.9 Bcm. That is around one third of the annual gas consumption of 35 Bcm a year, so when filled completely, these facilities will be able to buffer some of the demand for a while. However, similar to the UK, the Netherlands is also increasingly dependent on gas import, because of the imminent closure of the Groningen field and the depletion of small fields offshore are leading to a significant drop in domestic production to less than 20 Bcm a year in the time to come.

In Denmark, two onshore facilities are operational, one in a saline aquifer overlying a Zechstein salt dome and the other in a salt cavern. The combined capacity of the two is about 1 Bcm, which compared to an annual consumption of 2.3 Bcm looks quite healthy. With the Tyra redevelopment ongoing and expected to start up in the next few years, it can also be expected that Denmark will be self-sufficient in terms of gas consumption for some time.

Gas storage capacity in Norway is negligible, although it does take place in some man-made caverns in the west of the country. However, with Norway being a net gas exporter it is unlikely that the country will run into problems, especially when considered that the annual gas consumption is only 4 Bcm whilst total production amounts to around 17 Bcm.

In summary, the gap between the amounts of gas in storage available at very short notice and the annual demands, taking into account the reliance on gas import as well, clearly points to the UK being the most prone to experiencing issues related to price hikes if not issues in terms of supply. Given that some of the gas storage facilities are at the moment experiencing a significant lag in being refilled, the potential for disruption is only increasing.

HENK KOMBRINK