Late June, the Greenland Government announced that it will cease issuing new petroleum exploration licences, based on economic calculations as well as the role hydrocarbons play in causing climate change.

By doing so, the country joins other nations who recently have taken similar decisions such as France, Ireland and Spain.

However, the difference between for instance Spain and Greenland is that Greenland has more potential to become a hydrocarbon producing nation. For that reason, the national oil company NUNAOIL is in the midst of carrying out a major study, looking at the offshore resource potential of the Greenland Continental Shelf.

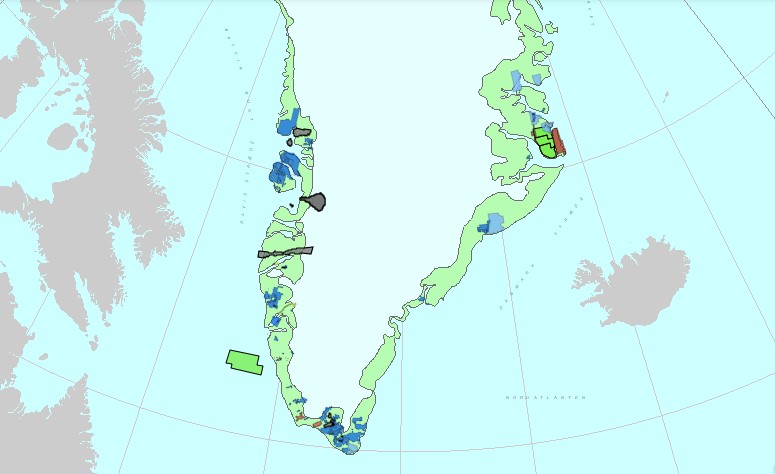

And even now that it is impossible to apply for further exploration licences, the company is intending to complete the study in order to have a rounded overview of what the area could potentially hold. So far, the West Greenland shelf assessment has finished through the publication of three digital reports and the fourth area – Northeast Greenland – is expected to be completed by the end of September.

Government U-turn

The decision to stop issuing exploration licence comes after a fairly recent attempt to attract oil exploration investment to Greenland. Only less than a year ago, the government offered a reduction in the government take from 51% to 41%. This U-turn now taken is probably down to the newly elected government that is more critical towards oil exploration than its predecessor.

A quick overview

Despite the under-explored nature of the Greenland shelves, several wells have been drilled and the area was on the radar of majors such as Statoil, Shell and ARCO. Most recently, it was Cairn that embarked on a major campaign in 2010-11 whereby a total 8 eight wells were drilled west of Greenland. However, out of the 15 exploration wells drilled in this area, no discoveries were made, and following the price collapse of 2014 most licences were relinquished.

No hydrocarbon exploration wells have yet been drilled along the eastern Greenland Continental Margin (East Greenland Rift Basin). This is mainly due the technical challenges posed by sea ice, as the USGS indicated that the area may hold around 31,400 MMboe. Also, given that the area forms the conjugate margin to the prospective Norwegian sector, it is again no surprise why there has been significant interest.

At the moment, there is only one active offshore licence, located on the west coast, and three small adjacent onshore licences in the east (The Jameson Land Basin). Any future activity in these licences seems to have become more challenging and finding project partners could be one of the stumbling blocks to progress these licences.

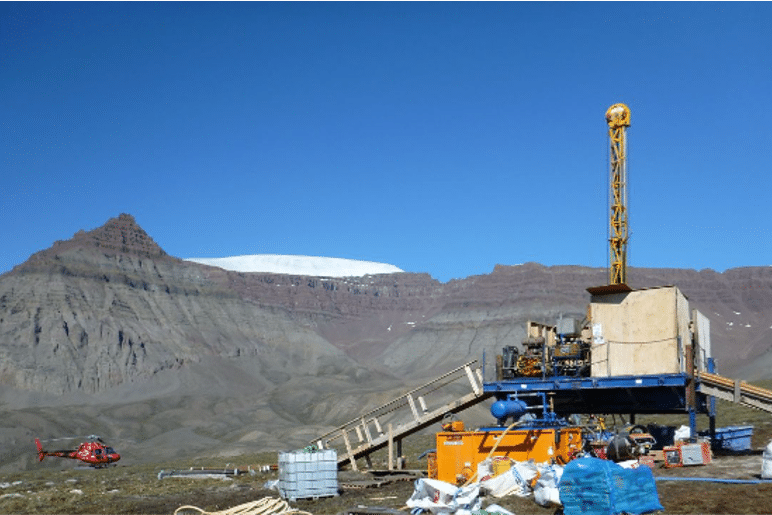

In contrast to hydrocarbon exploration, the government does support the mining sector, with a number of projects currently in both the exploitation as well as the exploration phase. However, a critical factor is the presence of uranium, which is not supposed to be traded and may put a spanner in the wheel of some projects.

In the meantime, as the NUNAOIL Hydrocarbon Assessment study progresses, we will continue to report on the findings.

HENK KOMBRINK