An adventurous life as a geologist around the world led Sir Mark Moody-Stuart to very senior roles in the oil and gas industry and a strong interest in sustainable development.

“There is no point in working unless you think what you are doing is worthwhile,” explains Sir Mark Moody-Stuart. “I’ve always thought that developing reliable, economical energy is a noble cause; the source may need to be different, but the fundamental underlying need remains.”

Mark Moody-Stuart

Inspired by Museums

Sir Mark has spent his career in large organisations but has a very independent mind when it comes to the best way that a business should be run, built on his wide experience throughout the world. Th e youngest of six, he was born in Antigua and has fond memories of the island, which he still visits regularly.

“After WWI my father was sent to run the family sugar estates in Antigua, where he met my mother, whose family had been there for decades,” he explains. “However, when I suggested I followed the family footsteps as an agri-industrialist in the Caribbean, my father declared there was no future in it; he realised the time of empire and colonisation would soon end and thought it only right that the industry should be turned over to the people who had been brought there as slaves. So I needed to find a different line of work.”

After starting his education in Antigua, Sir Mark went to boarding school in Shropshire, where he began to develop an interest in the rocks of that well-known geological area. He spent school holidays in London with his father’s three unmarried sisters (“typical of that First World War generation”), who would “shoo me out of the house with two bob in my pocket, so I spent a lot of time in the museums in Kensington, including the Natural History Museum and what was then the Geological Museum. The staff were very helpful and answered my questions – so I decided to study geology at Cambridge University.”

As an undergraduate, he went on an expedition to Spitsbergen, returning there to study its Devonian fluviatile sediments for his Shell-funded doctorate. “Then I had three choices: the National Coal Board, mining in southern Africa, or the oil industry? I didn’t fancy coal mines and the politics of southern African mining didn’t appeal to me – but Shell had some very good sedimentologists, publishing interesting papers, so I joined them.”

Sir Mark with Wen Jiabao, former Premier of China; “a real geologist, and a nice man”. © Mark Moody-Stuart.

The Travelling Geologist

Thus Sir Mark and his chemist wife Judy, who he had married while he was doing his PhD, began the life of the travelling exploration geologist. “I did field work in Spain in Franco’s time, while Judy was back in Cambridge with our son,” he tells me. “I then went to Oman, again on bachelor status but a very worthwhile experience. I was working with Ken Glennie, mapping the Al Hajar mountains for PDO [Petroleum Development Oman]; my speciality was the thrust elements – all very complicated – but it meant another year of separation, communicating by very slow letters.

“After that, however, we were in Brunei and in Australia together, before moving back to England when I briefly worked the North Sea. I was then asked to return to Brunei but not in exploration (Judy said that she’d had six years in the real world, so we might as well go back to camp life!), before an operational role in Nigeria – a great opportunity for us both to really understand a culture from the inside – then Turkey and Malaysia in general management, before we returned to The Hague for my senior management roles.”

These senior roles included Exploration and Production Coordinator and Group Managing Director in the early 90s. In 1998 Sir Mark became Chairman of the Shell Group, a position he held until 2001, remaining on the board until 2005. He was non-executive chairman of Anglo American from 2001–2009 and serves on the board of Saudi Aramco.

Leadership and Management

I asked Sir Mark what he thinks helped get him noticed in such a large company and thus enable such a successful and high-profile career. “When I originally joined Shell I did wonder how I would fit into this massive, highly efficient organisation – not being very well organised myself!” Sir Mark explains. “But from the time I started I always found things that ‘needed fixing’; that probably got me noticed. Also, we were flexible. I believe that if your boss says, ‘I think you should do this’, then your reaction should be to say yes; you’re being asked because the job needs doing and if somebody thinks you’re the best person to do it, why question it? I think my willingness to say yes and show commitment to the organisation was important in my progress through the company.

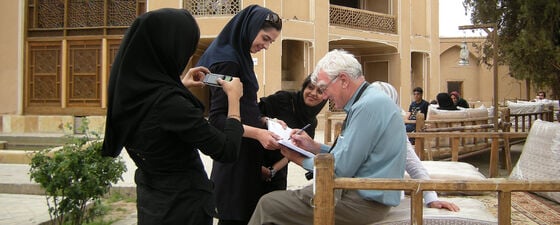

Sir Mark and young students in Iran. © Mark Moody-Stuart.

“I enjoy making things work, and that’s basically what management is,” he explains. “For example, in the late 70s I was asked to go to Brunei in the new post of Services Manager, overseeing the departments of logistics, procurement, services and maintenance to encourage them to work together more efficiently. The heads of these departments were all much older and more experienced than me and all very good. We all knew I could not do their jobs. Until then, as an exploration team leader I had a full understanding of the jobs of the people I was working with, increasing my knowledge through them. In this case I had to work with these managers to find out what was making their lives difficult and what they felt needed changing, working with them and others to find and deliver solutions. My function was to remove blockages in the system. This is true of most management positions; you’re basically a facilitator of the operational environment, ensuring that your team can do their jobs.

“That’s what I call stage 2 management; stage 1 is the football captain, who can do all the jobs to a certain extent. Stage 3 is when you are at the top of the organisation. You can see the broad direction in which you want to go but you don’t have the capacity for all the creativity needed, so instead you set up an environment with enough free rein for others to be creative, but within a controlled environment. Building strong trust is important. When I was a child in Antigua, we used to ride these rather wild ex-race horses, which would explode down a field at top speed whenever they could. All I could do was steer the horse – the organisation – to make sure it didn’t get into trouble. Similarly, you need to know when to give the organisation its head, but also safeguard the investment. Of course, it doesn’t always work!”

Sir Mark adds: “People talk about medicine, teaching and art as vocations; no one talks about business as one, but it is. Supplying honest, reliable goods and services gives enormous satisfaction, but it has to be done right.”

Sustainability and Social Responsibility

Sir Mark Moody-Stuart is Chairman of the Foundation for the United Nations Global Compact and was, until recently, the Vice Chair of the Global Compact Board, a non-binding pact to encourage businesses worldwide to adopt sustainable and socially responsible policies.

He was an early advocate of sustainable energy policies. “It’s linked to development really,” he explains. “Working and living around the world in different economies and seeing the contributions, both good and bad, that oil has made to countries gets you interested in development. The evolution of energy has usually been through technology and convenience – cars replacing horses, for example, or oil replacing coal for domestic heating. I always assumed that something would eventually come along to replace oil, but it was only in the 90s that we began to realise the potential effect of hydrocarbons on the climate.”

Sir Mark and his wife Judy in the UN General Assembly Hall. © Mark Moody-Stuart.

In 1995, as Group Managing Director, Sir Mark and Shell were faced with the twin challenges of the decommissioning of Brent Spar and associated public outcry, and the execution of Nigerian journalist and environmental activist, Ken Saro-Wiwa, whose death it was claimed Shell could have tried to prevent. “In response, we developed groups throughout the world,” he says. “Half of each group came from within Shell, sliced down through the company, and half were outsiders – journalists, politicians etc. We asked them to outline the responsibilities of a global company in the late 20th – early 21st century. We had always clearly stated that we don’t give bribes and we don’t get involved in politics, but it was felt that this was not sufficient any more. As a result of the groups’ findings we modified Shell’s principles to include, firstly, a commitment to human rights, and secondly, a realisation that we have a responsibility within political relationships to engage in politics and to express our views.

“The third commitment, which I think was the easiest to say but the least understood, was to sustainable development,” he continues. “We included an acknowledgement of the challenge of climate change in our 1996 annual report, the first major oil company formally to do so. At the time, people understood sustainable development to mean renewable energy, but of course it also includes hydrogen and carbon taxing and pricing as well as all the social aspects.”

Public Perception

Sir Mark believes the industry did not try hard enough to engage with civil society when it needed to. “In about 2002 the CBI [Confederation of British Industry] set up a working group covering industries from producers to users of oil to look at what we now call the energy transition. They came up with a set of excellent proposals, including carbon pricing, but rather than try to involve civil society in the creation of this report, they instead just presented it and asked for comments. As a result, its publication didn’t get much coverage; the feeling was that it had come from business so it must be biased.

“Compare that to action taken by the mining industry, which has also been hugely criticised,” he continues. “In the early 2000s they set up a group called ‘mining, minerals and sustainable development’ and involved civil society. Effectively, the industry said: ‘you need what we do but you don’t like how we do it, so let’s get together and find a different approach.’ Out of this came the International Council for Mining and Metals and a very open conversation with civil society, including charities. If the oil industry had similarly got people together earlier, we would have all realised we were working in the same direction, although with different ideas about how to do it. We would then have been able to talk to government together, to help them take positive steps. We should have had an alliance of oil industry leaders standing shoulder to shoulder with environmental groups.”

Looking to the Future

Sir Mark is on the advisory board of Envision Energy: “a highly creative Chinese company that is now the second largest wind turbine manufacturer in China, he explains. “When I talk to the founder, a very visionary man called Zhang Lei, I feel optimistic for the future. “The development of alternative energies is moving at a great pace. Oil companies have the cash flow that could be used to develop other energy sources; it’s the same mission, just a different source.

“We will need some of the majors to be involved in the energy transition to help develop an integrated system, which they can do while they have capacity and good cash flow. Hydrogen is important; in areas where wind and solar can produce more energy than needed, the over-capacity can be used to make hydrogen, which can in turn be used to decarbonise hard-to-reach sectors, like heavy transportation and shipping. Creating hydrogen by electrolysis is a better option for excess electricity than using batteries, because if we’re not careful we’ll soon find ourselves with another resource and disposal crisis over them.

“Sometimes I feel less optimistic and think that this is all going to take too long. Many predict that oil will still be in use for decades to come – but we need to remember the speed at which change can happen; take the spread of bioethanol from maize, for example, or the exponential rate at which fracking spread.

“Rapid change can happen – but it needs commerce to make it come about,” Sir Mark concludes.